The impact of surgical approach on quality of life for pleural malignant mesothelioma

Introduction

Past exposure to asbestos, either in an environmental and/or occupational setting is commonly associated with malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM). The average survival diagnosis for patients with MPM is around 15 months, despite a variety of multi-modal therapies such as tyrosine-kinase inhibitors, surgery and radiation, and platinum-based chemotherapy (1). Many immunotherapies are being tested for implementation, but further studies are needed to analyze their value (2). Palliative care is offered to most patients as many have an advanced stage of this disease, and commonly have numerous co-morbidities which prevent the usage of aggressive treatment. Controlling symptoms and improving the quality of life for these patients is the main goal of treatment, as a short life is anticipated from the time of diagnosis.

Surgical treatment is presently performed in 22% of MPM patients (3) and was found to be an independent predictor of extended survival in a SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) analysis (1). Questions remain as to which surgical procedure, extrapleural pneumonectomy (EPP) or pleurectomy (P/D), is most effective and results in better outcomes for survival and involves fewer complications (4). Recent research illustrated that P/D may be slightly more effective in terms of both short and long term survival, but that the differences are not pronounced (5). To help guide patients in making educated decisions as to which treatment would be best for them, it is important to analyze how quality of life is affected by both EPP and P/D. The current study involved the conduct of an analytic review of published manuscripts that examine the differential impact of surgical treatment for MPM on quality of life (QoL) among patients treated with EPP as compared to P/D.

Methods

The key words “quality of life” AND “mesothelioma” AND “surgery” were used to perform a MEDLINE search. In addition, a review on quality of life after mesothelioma treatment (6) and meta-analyses on surgical outcomes for mesothelioma (7-9) were examined. Data on QoL after surgical resection for MPM was extracted. Articles written in English were included in this current review.

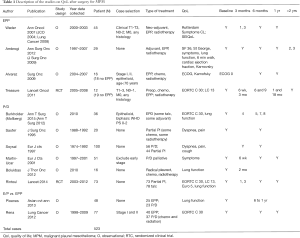

After abstracts were reviewed, 16 out of 94 possible articles were included. The other 78 articles were case report publications, did not include mesothelioma cases/quality of life information, commentary, and/or did not report cases that were treated with surgery. The final 16 articles were thoroughly reviewed to reveal another article that fit our exclusion criterion because of a barrier in language (10). This left 15 articles and 12 distinct datasets for a total of 523 pleural mesothelioma patients with QoL information (Table 1). Two reviewers (ET, AW) extracted data independently and in cases of discordance, a determination was reached after discussion with a third reviewer (RS).

Full table

Results

QoL after EPP

Data from a total of 102 patients were extracted from four datasets that analyzed QoL after EPP, (3 observational datasets and 1 randomized clinical trial.) In a study by Weder and colleagues, QoL was assessed in 45 patients who received neo-adjuvant chemotherapy, EPP and then possible adjuvant radiation using the Rotterdam Symptom Checklist, a cancer-specific questionnaire which measures psychological and physical distress (11). Quality of life was analyzed before and after surgery at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months. After 6 months, psychological distress mirrored values similar to those of the baseline assessment. After 1 month, physical symptoms had worsened overall for the patients (–16.7 from baseline) but improved after 6 months post-surgery (–4.3). Overall QoL did not reach baseline levels after 6 months (–8.3). Additional symptoms that were reported such as chest pain, tiredness, and shortness of breath worsened at 1 month, but returned to baseline after 6 months (11). Patients were also provided the SEIQoL-DW, (the Schedule for the Evaluation of Quality of Life-Direct Weighting), to analyze and rate what each patient deemed as the five most important quality of life domains in their life. Overall SEIQoL-DW QoL scores decreased after surgery, then returned to baseline at 3 months, and then worsened again at 6 months (12).

Twenty nine patients who underwent adjuvant chemotherapy, EPP, and adjuvant radiation, were analyzed in the Ambrogi study (13,14). QoL measurements were reported at baseline and were recorded up to 3 years after surgery. Six months post-surgery, cardiac and lung function within the patient sample was stable, but had significantly decreased 12 months after the EPP. The Karnofsky Performance Status index [a 100 point measurement of performance status with 100 being normal and 0 as lowest (deceased)], as well as dyspnea, pain, cough and fever improved at 3 months, but declined again at the 12 months mark post-surgery. A 36-item survey of mental and health QoL summary measures, the SF-36, showed improvement in all domains at the 3 month mark, but only remained above baseline in the physical QoL domains at 12 months. Two years after surgery, both of these scores were below baseline. The St. George respiratory questionnaire also indicated similar results.

The comparison of quality of life after EPP to no surgery was assessed by two studies, one observational study and one randomized controlled trial. Sixteen patients with stage I or II epithelioid mesothelioma who were treated with EPP, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy and had an ECOG (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group) performance status score of 0, were studied by Alvarez and colleagues (15). For the 6 months and 1 year mark after surgery, both ECOG and Karnofsky scores were reported, however, there were no baseline measures accessible for comparison. Mean ECOG scores at 6 months and 1 year were 1 and 0.8, respectively, while the Karnofsky index scores for the same intervals were 74 and 2. To clarify these scores, a stable mean ECOG score of 1.7 and a Karnofsky score of 46 at 6 and at 12 months was reported for patients who did not undergo surgery (n=18). A feasibility trial was conducted by Treasure et al. (16), randomizing patients to EPP or no surgery. Twelve patients underwent induction chemotherapy, EPP and adjuvant radiation in this study. Both the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC-30) quality of life survey and a lung cancer-specific questionnaire (LC-13) were used to assess QoL, and the scores were compared to the control groups’ scores, who were undergoing chemotherapy only. Although the QoL was worse after EPP (33.3) compared to no surgery [75], particularly at the 6-week mark, the QoL scores were not statistically significantly different at any of the time points.

QoL after P/D

Six studies evaluated quality of life after P/D, with a total of 296 patients analyzed. In Burkholder’s study (17,18), patients who completed the EORTC-30 questionnaire at baseline and up to 8 months after P/D were analyzed (N=36). Some patients were additionally treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and/or underwent a pleurodesis procedure. All but emotional function scores stayed the same amongst patients with a favorable QoL profile at baseline and who had a ECOG performance status (PS) of 0, with emotional function considerably increasing during follow-up. PS 1 and PS 2 patients improved at 4–5 months with continuous improvement at the 7–8 months mark in every domain. Lung function parameters were significantly decreased in the PS 0 patients whereas there was no change found in the PS1/PS2 patients for these factors. In Sauter’s study (19), data from 36 patients treated with partial pleurectomy with various combinations of chemotherapy and radiation were analyzed. Both baseline and follow up values for specific symptoms were reported. Pain improved in 21% of the patients after surgery, while dyspnea improved in 47% of the patients.

A retrospective analysis of symptoms was conducted by Soysal et al. (20) of 100 patients who either underwent P/D or a partial pleurectomy. Baseline and 6 month values were recorded for general symptoms. Chest constriction decreased in 30%, dyspnea in 37%, cough in 40%, and chest pain in 71% of patients. Martin-Ucar et al. (21) excluded cases of EPP patients with early stage disease, but reported symptoms of 51 consecutive patients who underwent P/D surgery using the Medical Research Council (MRC) Dyspnoea Scale. Dyspnea and pain scores increasingly improved at the 6 week and 3 month time points. Bölükba et al. (22) reported on symptoms of 16 patients who were treated with radical pleurectomies, then chemotherapy and radiation. From baseline to 2 month follow up, measurements for all functional parameters improved. An RCT was conducted by Rintoul et al. (23), comparing the talc pleurodesis procedure with a partial pleurectomy in 151 patients, of which 73 had surgery. QoL was assessed by administering 3 different QoL questionnaires at baseline and throughout the first year after surgery (i.e., the EuroQoL 5D, the EORTC C30, the Lung Cancer LC13). EuroQoL scores significantly declined 1 month after surgery, but returned to baseline values after 3–4 months and continued to show improvement at 12 months. One month after surgery, the cognitive, physical and role function scales of the EORTC were lower than at baseline, but then increased to levels that were reported before surgery at 3, 6, and 12 months. Emotional/social function scales and global health better at 1 year follow up as compared to pre-surgery, but returned to pre-surgery levels at 3, 6 and 12 months follow up. Lung function improved 1 month after surgery and continued to progress throughout follow up.

QoL comparison between EPP and P/D

EPP and P/D were directly compared in only two studies within our review. Lung function was analyzed at baseline and at 6 and 12 months following surgery by Ploenes et al. (24), in 23 patients who underwent P/D and 25 patients who had an EPP procedure. Compared to the P/D patients, EPP patients had reduced pulmonary function. Dyspnea was worse in EPP patients than in P/D patients, and cough and pain were comparable within both groups. Further, seventy seven patients with either stage I or stage II mesothelioma were studied by Rena et al. (25) who underwent an EPP procedure (N=40) or had an P/D (N=37). At baseline, 6 months after surgery, and 12 months after surgery, patients were given the EORTC questionnaire to assess any change within QoL measurements. Both EPP and P/D caused a significant decrease within all EORTC-QLQ-C30 (QoL) variables at the 6 month mark. EPP patients had a greater deterioration in QoL measurements than patients who underwent P/D, and only P/D patients demonstrated returns to baseline values at 12 months post-surgery.

Conclusions

This review illustrates that QoL measurements such as lung function parameters, physical symptoms and physical and social functions, are significantly affected by both EPP and P/D 6 months after surgery. Although few studies have directly compared the two procedures, it appears that P/D patients tend to have better QoL outcomes. This is not surprising given that increased morbidity has been associated with EPP more often than with P/D. It is possible that the decision regarding surgical approach was based on comorbidities and clinical indications that could also be responsible for some of the QoL outcomes that were present. Ploenes et al. (24) addressed this potential selection bias by ensuring that that baseline lung function was comparable between the two groups. In fact, often patients who have been guided to undergo the P/D procedure instead of the EPP procedure tend to have more acute comorbidities which make them less likely to be candidates for EPP therefore reinforcing the validity of the findings regarding more positive QoL outcomes in P/D patients.

Most studies in this review were stratified for stage of cancer, so theories from critics of P/D who might posit that the higher tumor burden of EPP patients could have a negative impact on Qol measures are not valid. In an updated supplement provided by Treasure [2015], he notes that EPP offers no benefit of survival or increase in QOL, based on data collected from large cohort studies. Treasure ultimately suggests that the EPP procedure should be a surgery of the past (4).

This review illustrates the need to include QoL assessments within MPM research in order to better understand the association between MPM surgical resections and QoL. Although there is an extensive amount of literature found for MPM surgery, only 12 datasets included QoL measures (12 datasets). Some studies within this review involved datasets with very small sample sizes indicating the need for larger cohort studies of MPM surgical patients.

Further, it was very challenging to assess QoL from a standard point of measurement, as many of the instruments used to analyze QoL (such as the lC-30 and the EORTC) were extremely different from another and non-comparable. There was also a high variance in intervals of time at which QoL information was collected and not all studies included baseline data making it more difficult to assess changes in QoL across time. Many additional treatments were provided to patients, such as chemotherapy and radiation, but their specific effect on quality of life measures was not reported. There was extensive heterogeneity in many factors within the studies, such as stage, comorbidities, and age. It is possible that the VATS approach (video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery) was utilized instead of the normal thoracotomy in many resections recorded throughout the studies used. This difference in approach could have an effect on QoL, but was not reported. In addition, more QoL data was found for P/D patients than EPP patients (356 to 167, respectively) and if more EPP data was collected, the conclusions might have differed.

Further, missing patient data could be due to loss to follow-up for systematic reasons. For example, patients who are extremely sick or who are doing much better than most may not remain in clinical studies. Studies that account for these directional biases could generate a more accurate assessment of the surgical impact on QoL.

In conclusion, although this review generally finds that P/D has better QoL outcomes for MPM surgical patients, more comprehensive cohort studies are needed. MPM patients and surgeons could greatly benefit from this increased body of knowledge when engaging in surgical decision making.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Taioli E, Wolf AS, Camacho-Rivera M, et al. Determinants of Survival in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Study of 14,228 Patients. PLoS One 2015;10:e0145039. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hoda MA, Klikovits T, Arns M, et al. Management of malignant pleural mesothelioma-part 2: therapeutic approaches: Consensus of the Austrian Mesothelioma Interest Group (AMIG). Wien Klin Wochenschr 2016;128:618-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Flores RM, Riedel E, Donington JS, et al. Frequency of use and predictors of cancer-directed surgery in the management of malignant pleural mesothelioma in a community-based (Surveillance Epidemiology, and End Results[SEER]) population. J Thorac Oncol 2010;5:1649-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Treasure T. Extrapleural pneumonectomy for malignant pleural mesothelioma: is this an operation that should now be consigned to history? Future Oncol 2015;11:7-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Taioli E, Wolf AS, Flores RM. Meta-analysis of survival after pleurectomy decortication versus extrapleural pneumonectomy in mesothelioma. Ann Thorac Surg 2015;99:472-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Papaspyros S, Papaspyros S. Surgical management of malignant pleural mesothelioma: impact of surgery on survival and quality of life-relation to chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and alternative therapies. ISRN Surg 2014;2014:817203. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cao CQ, Yan TD, Bannon PG, et al. A systematic review of extrapleural pneumonectomy for malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Thorac Oncol 2010;5:1692-703. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lang-Lazdunski L. Surgery for malignant pleural mesothelioma: why, when and what? Lung Cancer 2014;84:103-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rintoul RC. The MesoVATS trial: is there a future for video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery partial pleurectomy? Future Oncol 2015;11:15-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Colaut F, Toniolo L, Vicario G, et al. Pleurectomy/decortication plus chemotherapy: outcomes of 40 cases of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Chir Ital 2004;56:781-6. [PubMed]

- Weder W, Stahel RA, Bernhard J, et al. Multicenter trial of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy followed by extrapleural pneumonectomy in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Ann Oncol 2007;18:1196-202. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ribi K, Bernhard J, Schuller JC, et al. Individual versus standard quality of life assessment in a phase II clinical trial in mesothelioma patients: feasibility and responsiveness to clinical changes. Lung Cancer 2008;61:398-404. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ambrogi V, Baldi A, Schillaci O, et al. Clinical impact of extrapleural pneumonectomy for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:1692-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ambrogi V, Mineo D, Gatti A, et al. Symptomatic and quality of life changes after extrapleural pneumonectomy for malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Surg Oncol 2009;100:199-204. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alvarez JM, Hasani A, Segal A, et al. Bilateral thoracoscopy, mediastinoscopy and laparoscopy, in addition to CT, MRI and PET imaging, are essential to correctly stage and treat patients with mesothelioma prior to trimodality therapy. ANZ J Surg 2009;79:734-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Treasure T, Lang-Lazdunski L, Waller D, et al. MARS trialists. Extra-pleural pneumonectomy versus no extra-pleural pneumonectomy for patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma: clinical outcomes of the Mesothelioma and Radical Surgery (MARS) randomised feasibility study. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:763-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Burkholder D, Hadi D, Kunnavakkam R, et al. Effects of extended pleurectomy and decortication on quality of life and pulmonary function in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. Ann Thorac Surg 2015;99:1775-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mollberg NM, Vigneswaran Y, Kindler HL, et al. Quality of life after radical pleurectomy decortication for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Ann Thorac Surg 2012;94:1086-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sauter ER, Lancer C, Coia LR, et al. Optimal management of malignant mesothelioma after subtotal pleurectomy: revisiting the role of intrapleural chemotherapy and postoperative radiation. J Surg Oncol 1995;60:100-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Soysal O, Karaoğlanoğlu N, Demiracan S, et al. Pleurectomy/decortication for palliation in malignant pleural mesothelioma: results of surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1997;11:210-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martin-Ucar AE, Edwards JG, Rengajaran A, et al. Palliative surgical debulking in malignant mesothelioma. Predictors of survival and symptom control. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2001;20:1117-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bölükba S, Eberlein M, Schirren J. Prospective study on functional results after lung-sparing radical pleurectomy in the management of malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Thorac Oncol 2012;7:900-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rintoul RC, Ritchie AJ, Edwards JG, et al. Efficacy and cost of video-assisted thoracoscopic partial pleurectomy versus talc pleurodesis in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma (MesoVATS): an open-label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 2014;384:1118-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ploenes T, Osei-Agyemang T, Krohn A, et al. Changes in lung function after surgery for mesothelioma. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2013;21:48-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rena O, Casadio C. Extrapleural pneumonectomy for early stage malignant pleural mesothelioma: a harmful procedure. Lung Cancer 2012;77:151-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]