Molecular mechanisms of programmed cell death-1 dependent T cell suppression: relevance for immunotherapy

Introduction

After decades of extensive research in the development of cancer immunotherapies, during the last ten years these therapies have achieved clinical success. Among the most promising approaches is the blockade of immune checkpoints that regulate immune responses. T cell antigen recognition is highly regulated by co-stimulatory positive and negative signals. Under normal immune responses, negative signals called immune checkpoints are critical to maintain peripheral tolerance and protection from autoimmunity. However, inhibitory ligands and receptors of these immune checkpoints are frequently up-regulated in tumors. Programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 (PDL1)-programmed cell death-1 (PD1) together with CD80-CTLA4 interactions are one of the best known by their clinical relevance. PD1 is a type 1 transmembrane protein expressed by many effector immune cells. In fact, PD1 expression is up-regulated following T and B cell activation. Its receptor PDL1, a member of the B7 family of co-stimulatory/co-inhibitory molecules is expressed by many cell types including antigen presenting cells such as dendritic cells and cancer cells (1). Importantly, PDL1 is commonly overexpressed in several cancer types as an immune resistance mechanism (2,3). PDL1 on the surface of cancer cell binding to PD1 on T cells causes T inactivation within the tumor microenvironment (4).

The application of PDL1/PD1 monoclonal antibody immunotherapy has demonstrated efficacious clinical responses in diverse human cancers. An increasing number of clinical trials demonstrate that PDL1/PD1 blockade is remarkably more effective than conventional therapies in many cases, with durable clinical responses and milder side effects (5). This therapy enhances T cell responses toward cancer cells while surprisingly sparing non-transformed cells. Nevertheless, a significant number of patients are intrinsically resistant to these therapies. The uncovering of the molecular mechanisms in which the efficacy of PD1/PDL1 targeted therapies relies may identify non-responder patients.

Mechanisms of antigen presentation to T cells

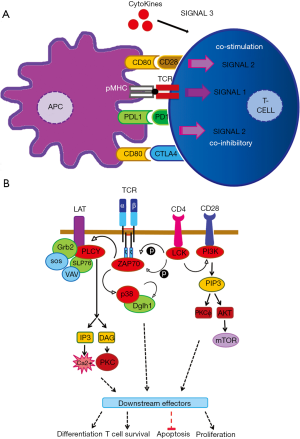

T cell activation is highly regulated at multiple levels especially during antigen presentation to ensure a proper immune response. T cells recognize peptides derived from antigens through their surface T cell receptor (TCR). This recognition relies on the establishment of an immune synapsis established by the TCR with antigenic peptide-major histocompatibility molecules (p-MHC), and stabilized by a range of positive and negative interactions between the T cell and the antigen presenting cell (Figure 1A). The relative contribution of co-stimulatory/co-inhibitory ligand-receptor interactions determines the activation state and the type of effector T cell responses (6,7). The main positive regulatory interaction is provided by CD80 on the surface of APC which binds to CD28. On the other hand, negative regulatory signals (immune-checkpoints) modulate this recognition to ensure self-tolerance and protection against exacerbated immune responses (8). Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA4) and PD1 on T cell surface regulate negatively immune responses binding to CD80 and PDL1, respectively. Finally, cytokine-dependent signals regulate T cell differentiation and effector capacities.

At the molecular level, when the TCR α and β chains associated to CD3 molecules recognize the p-MHC together with CD4 or CD8 clustering, a complex signaling pathway is started (Figure 1B). The signaling events begin with the recruitment and activation of Src/like tyrosine kinases such as LCK into the signaling complex. These kinases phosphorylate the TCR and CD28 intracellular chains allowing the TCR signal transduction to proceed through the recruitment of ZAP-70 and PI3K to the CD3 and CD28 molecules, respectively (9). With the phosphorylation of additional T cell molecules such as LAT and p38, signal transduction continues through the recruitment of other molecules such as GRB2, VAV and SOS, culminating with the activation of MAPKs ERK and JNK (10-12). PLCγ1 also gets activated causing the release of Ca2+ ions from the cell endoplasmic reticulum and NFAT (Nuclear factor of activated T-cells) and CREB translocation to the nucleus. PKC isoforms also get activated which participate in the nuclear factor NF-kappa-B (NF-kB) pathway (13). These events induce also the activation of RasGRP1 leading to ERK activation (14).

The co-stimulatory interaction between CD80 and CD28 reinforces T cell activation signaling. CD80-CD28 association recruits PI3K to CD28 intracytoplasmic domain and then gets activated producing phosphatidylinositol [3,4,5]-triphosphate (PIP3) which is required for AKT and PKCƟ activation and therefore Bcl-x expression. AKT through the mTOR pathway rescues T cells from anergy (15), while PKCƟ activates NF-kβ and MKK7 required to Il-2 production.

Mechanisms of pd1-dependent T cell suppression

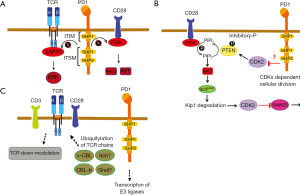

During antigen presentation PDL1-PD1 engage within the immunological synapse blocking T cell activation, proliferation and acquisition of effector capacities (16) by strongly inhibiting TCR signal transduction and CD28-CD80 costimulation (17). However, PD1 plays also critical roles in physiological conditions by fine-tuning the activation state of T cells following their activation. Therefore, PD1 is up-regulated in naïve T cells following antigen presentation (18). PD1 consists of a single N-terminal immunoglobulin variable region-like domain, a transmembrane domain, and a cytoplasmic domain containing tyrosine-based signal motifs. These includes an immunoreceptor tyrosine based inhibitory motif (ITIM) and an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based switch motif (ITSM) (Figure 2A). All the data point to the ITSM motif as the mediator of PD1 inhibitory signaling activities (19). PD1 exerts its immunosuppressive activities by recruiting phosphatases containing SH2 domains, SHP1 and SHP2 to the tyrosine-based motifs (20). During T cell antigen recognition, when TCR signal transduction is activated these motifs undergo phosphorylation by LCK. If in that situation PD1 binds to its receptor PDL1, the TCR signal transduction terminates through several mechanisms. The first one includes the SHP-mediated dephosphorylation of the TCR signalosome components (4). More specifically, the dephosphorylation of CD3ζ, ZAP70 and PI3K kinases resulting in the deactivation of downstream signaling targets (21,22). Although both SHP1 and SHP2 interact with ITSM motif (19) it has been shown that only SHP2 binds to the ITSM during T cell activation (21). Moreover, SHP2 but not SHP1 has been found associated to PD1 in microclusters (23). Therefore, most of the evidence points to SHP2 as the main mediator of PD1 inhibitory effects, while the participation of SHP1 is still under debate.

Apart from proximal inhibitory effects over the TCR signalosome, PD1 can also suppress T cell activation through indirect pathways mostly affecting T cell proliferation. Upon T cell activation, TCR signal transduction increases CK2 expression that phosphorylates the regulatory domain of PTEN which inhibits its phosphatase activity over PIP3 produced by PI3K (24) (Figure 2B). If PD1 is engaged, CK2 kinase expression is down-regulated and PTEN can terminate PI3K activities by dephosphorylating PIP3 (Figure 2B) (25). Furthermore, PD1 can also inhibit cyclin-dependent kinase (CDKs) resulting in the arrest of T cell proliferation (Figure 2B). PD1 achieves this by inhibiting the transcription of the SCFskp2 following AKT and ERK inhibition. SCFskp2 is a ubiquitin ligase that targets the CDK2 inhibitor p27Kip1 for proteosomal degradation. In the absence of SCFskp2 the CDK2 inhibitor accumulates stopping cell division (22). This mechanism is also reinforced through the absence of the CDK2-dependent SMAD3 inhibiting phosphorylation. SMAD3 activities transactivates genes that encode CDK4, CDK6 and CDC25A transcriptional repressors (26). All in all, PD1-dependent T cell function inhibition is a complex mechanism that implicates several signaling pathways (27).

PD1 can also control the surface expression levels of the TCR, avoiding the recognition of pMHC by the T cell. Although the molecular mechanisms leading to TCR down-modulation are still unclear, most of the studies point to E3 ubiquitin ligases as the main mediators of PD1-depedent control of TCR expression. Particularly, the E3 ubiquitin ligases of the CBL family plays a critical role in regulating TCR expression levels and antigen-induced TCR down-modulation that takes place during antigen presentation. CBL knockout mice demonstrated that E3-ubiquitin ligases CBL-B, c-CBL and ITCH up-regulation induce the termination of TCR signal transduction (8,28,29) (Figure 2C). CBL-B and ITCH have been shown to cause the ubiquitination of CD3 and CD28 chains preventing their phosphorylation and the association of TCR signalosome kinases such as ZAP-70 and PI3K (30,31). PDL1-PD1 interactions during antigen presentation by dendritic cells to T cells cause the strong up-regulation of CBL-b and c-CBL which contributes to antigen-induced TCR down-modulation (8,28). It is highly likely that this process is also taking place within the tumor environment, as PD1 expression is up-regulated in tumor-infiltrating T cells and these T cells usually show low expression levels of surface TCR (32,33).

Upon activation T cells undergo a metabolic reprogramming to cover high energy needs. While quiescent T cells use lipid degradation to obtain the energy, aerobic glycolysis becomes the dominant energy source by effector T cells. An increment of glutamine uptake and catabolism is also required. When PD1 is engaged a suppression of oxygen consume takes place and aerobic glycolysis is no longer used. In this situation, fatty-lipid oxidation is the main energy source (34,35) (Figure 3). Moreover, accumulation of polyunsaturated fatty acids is another characteristic of the suppressed T cells (36). PI3K-AKT and ERK are known to induce the expression of glycolysis genes, so the resulting metabolism pattern change might be mediated by PD1-dependent inhibition of this signaling axis (35). As a consequence, PD1-engaged T cells also increase production of reactive oxidative species derived from fatty acid oxidation contributing to create an oxidative environment (37). Overall, PD1 engagement causes a shift on the metabolic reprogramming from an effector T phenotype to a memory-like phenotype. Interestingly enough, this metabolic changes might have an important contribution in PD1-dependent T cell suppression in cancer (38).

Functional consequences of PDL1-PD1 disruption

Cancer cells upregulate PDL1 surface expression to escape from host immune responses. This upregulation is mediated by inflammatory cytokines such as interferon γ (39). In addition, PDL1 expression is also regulated by oncogenic pathways including AKT and PTEN (40). When there is lymphocyte infiltration in tumors, these are mainly PD1high memory T cells specific for tumor-antigens (7,32). PDL1-PD1 engagement inactivates these tumor-specific T cells (41), and blockade of this interaction rescues these T cells from inhibition. Recent studies have demonstrated that PD1 blockade selectively increase CD8 memory T cell numbers within the tumor microenvironment with a concurrent increase in INF-γ production. This infiltration positively correlates with therapeutic efficacy. For example, in melanoma patients with PD1 CD8 T cells in the tumor before the treatment, and the increase of this population following treatment correlates with tumor regression (42). For this reason, CD8 T cell infiltration can be used as a biomarker for therapeutic efficacy. Actually, tumor infiltration with PD1high and CTLA4high exhausted CD8+ T cells has been proposed as an accurate predictor of responses to anti-PD1 therapy in melanoma (43).

Recently published studies in lung cancer have shown that T cells expanding in peripheral blood during anti-PD1 therapy are predominately CD28+ CD8 T cells. These findings points suggest that CD28-coestimulation might contribute to the reactivation of exhausted CD8 T cells in the tumor (44). Thus, it assigns to CD28 a possible function as a biomarker to predict PD1-antibody therapy efficacy. Nevertheless, it is still not clear where this co-stimulation takes place, either within the tumor driven by cancer cells co-expressing CD80, or systemically in secondary lymphoid organs. In fact, PDL1-PD1 interactions have a key role in the maintenance of peripheral tolerance. Since PDL1/PD1 blockade therapies are administrated systematically, such disruption must have a range of effects in the immunological synapse in peripheral tissues. When PDL1 is silenced in the peripheral tissues there is in fact an expansion of polyclonal CD8 T cells (43). Moreover, disruption of PDL1-PD1 interactions abrogates TCR down-modulation leading to the expansion of hyperactivated TCRhigh T cells. The differentiation of this pool of hyperactivated T cells might strongly contribute to anti-tumor responses in PDL1-PD1 blockade therapy, explaining in addition the role of CD80-CD28 interactions for therapeutic efficacy. As a consequence, a pool of these cells in some patients may manifest auto-reactive inflammatory adverse events which cause damage to tissues and organs (28,44).

The clinical application of PDL1-PD1 blockade therapies in patients with a wide range of cancers has demonstrated important therapeutic efficacies and long-lasting responses overtime. However, there is still a significant group of patients who do not respond to these therapies. Therefore, a key issue nowadays is the identification of predictive biomarkers for these therapies. It is assumed that PDL1 expression in cancer cells would directly correlate with therapeutic efficiency. However, patients with either PDL1-positve or PDL1-negative tumors can respond to these treatments (45). The presence of inactivating mutations in JAK1, JAK2 and beta2-microglobulin genes in cancer cells correlates with lack of response (46). Furthermore, there is also a correlation between tumor mutation burden with better clinical response. For example, non-squamous lung cancer (NSCLC) and melanoma are cancer types with a high number of somatic mutations. These cancers are frequently clinically responsive to anti-PD1/PDL1 therapy (47). Similarly, patients with microsatellite instability colorectal cancer show good responses while patients with mismatch repair-proficient colorectal cancer do not (48).

As mentioned before, the lymphocyte infiltration and its location within the tumor seems a good prognostic marker for immunotherapies (42). Furthermore, T cells exhibiting a Th1 phenotype in the tumor infiltrate also correlate with good responses and survival in some human cancers (49).

Conclusions

The therapeutic application of PDL1/PD1 blocking antibodies has revolutionized cancer treatments and care. Their efficacies and durable effects have opened a new line of first line treatments. PDL1-PD1 antibody-mediated blockade was recently approved by FDA for metastatic melanoma, NSCLC, head and neck, kidney and urothelial carcinoma. Moreover, several clinical trials undergoing with several cancer types have promising responses. However, this therapy is still refractory for a significant number of patients and the molecular bases of this unresponsiveness are still unclear. PDL1-PD1 interactions mediates immunosuppression by several mechanisms that are still under study. The uncovering of the molecular mechanisms governing their actions is relevant for a better understanding of therapeutic responses. Such discoveries will reveal novel biomarkers to predict whether patients will benefit or not from anti-PD1/PDL1 therapies. Furthermore, it will also provide new targets to enhance therapeutic intervention for those patients who will not respond.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Gobierno de Navarra, the “Precipita” crowdfunding project grant from Fundación Española para la Ciencia y la Tecnología (FECYT), “Sandra Ibarra” Foundation, the “Navarrese Association against Breast Cancer” (SARAY), “Caixa Foundation” and ISCIII (FIS. PI14/00579 project grant) for their financial support.

Funding: M Gato-Cañas is funded by a Government of Navarre PhD fellowship (BMED 033-2014); M Zuazo is funded by PhD studentship from the Universidad Publica de Navarra; M Ibañez-Vea is funded by a Sara Borrel post-doctoral fellowship. D Escors is funded by a “Miguel Servet” Fellowship (CP12/03114) from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), Spain. G Kochan is funded by a “Proyecto Tractor ProCel” from the Government of Navarre.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Sharpe AH, Wherry EJ, Ahmed R, et al. The function of programmed cell death 1 and its ligands in regulating autoimmunity and infection. Nat Immunol 2007;8:239-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Konishi J, Yamazaki K, Azuma M, et al. B7-H1 expression on non-small cell lung cancer cells and its relationship with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and their PD-1 expression. Clin Cancer Res 2004;10:5094-100. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dong H, Strome SE, Salomao DR, et al. Tumor-associated B7-H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: a potential mechanism of immune evasion. Nat Med 2002;8:793-800. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Freeman GJ, Long AJ, Iwai Y, et al. Engagement of the PD-1 immunoinhibitory receptor by a novel B7 family member leads to negative regulation of lymphocyte activation. J Exp Med 2000;192:1027-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gato-Cañas M, Arasanz H, Blanco-Luquin I, et al. Novel immunotherapies for the treatment of melanoma. Immunotherapy 2016;8:613-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Greenwald RJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. The B7 family revisited. Annu Rev Immunol 2005;23:515-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zou W, Chen L. Inhibitory B7-family molecules in the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Immunol 2008;8:467-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nurieva R, Thomas S, Nguyen T, et al. T-cell tolerance or function is determined by combinatorial costimulatory signals. Embo J 2006;25:2623-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chan AC, Iwashima M, Turck CW, et al. ZAP-70: a 70 kd protein-tyrosine kinase that associates with the TCR zeta chain. Cell 1992;71:649-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sieh M, Batzer A, Schlessinger J, et al. GRB2 and phospholipase C-gamma 1 associate with a 36- to 38-kilodalton phosphotyrosine protein after T-cell receptor stimulation. Mol Cell Biol 1994;14:4435-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Round JL, Humphries LA, Tomassian T, et al. Scaffold protein Dlgh1 coordinates alternative p38 kinase activation, directing T cell receptor signals toward NFAT but not NF-kappaB transcription factors. Nat Immunol 2007;8:154-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tybulewicz VL. Vav-family proteins in T-cell signalling. Curr Opin Immunol 2005;17:267-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin J, Weiss A. T cell receptor signalling. J Cell Sci 2001;114:243-4. [PubMed]

- Bivona TG, Perez De Castro I, Ahearn IM, et al. Phospholipase Cgamma activates Ras on the Golgi apparatus by means of RasGRP1. Nature 2003;424:694-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Salvador JM, Mittelstadt PR, Guszczynski T, et al. Alternative p38 activation pathway mediated by T cell receptor-proximal tyrosine kinases. Nat Immunol 2005;6:390-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Riley JL. PD-1 signaling in primary T cells. Immunol Rev 2009;229:114-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boise LH, Minn AJ, Noel PJ, et al. CD28 costimulation can promote T cell survival by enhancing the expression of Bcl-XL. Immunity 1995;3:87-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ishida Y, Agata Y, Shibahara K, et al. Induced expression of PD-1, a novel member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily, upon programmed cell death. Embo J 1992;11:3887-95. [PubMed]

- Chemnitz JM, Parry RV, Nichols KE, et al. SHP-1 and SHP-2 associate with immunoreceptor tyrosine-based switch motif of programmed death 1 upon primary human T cell stimulation, but only receptor ligation prevents T cell activation. J Immunol 2004;173:945-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Neel BG, Gu H, Pao L. The 'Shp'ing news: SH2 domain-containing tyrosine phosphatases in cell signaling. Trends Biochem Sci 2003;28:284-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sheppard KA, Fitz LJ, Lee JM, et al. PD-1 inhibits T-cell receptor induced phosphorylation of the ZAP70/CD3zeta signalosome and downstream signaling to PKCtheta. FEBS Lett 2004;574:37-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patsoukis N, Brown J, Petkova V, et al. Selective effects of PD-1 on Akt and Ras pathways regulate molecular components of the cell cycle and inhibit T cell proliferation. Sci Signal 2012;5:ra46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yokosuka T, Takamatsu M, Kobayashi-Imanishi W, et al. Programmed cell death 1 forms negative costimulatory microclusters that directly inhibit T cell receptor signaling by recruiting phosphatase SHP2. J Exp Med 2012;209:1201-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Torres J, Pulido R. The tumor suppressor PTEN is phosphorylated by the protein kinase CK2 at its C terminus. Implications for PTEN stability to proteasome-mediated degradation. J Biol Chem 2001;276:993-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patsoukis N, Li L, Sari D, et al. PD-1 increases PTEN phosphatase activity while decreasing PTEN protein stability by inhibiting casein kinase 2. Mol Cell Biol 2013;33:3091-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patsoukis N, Sari D, Boussiotis VA. PD-1 inhibits T cell proliferation by upregulating p27 and p15 and suppressing Cdc25A. Cell Cycle 2012;11:4305-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wei F, Zhong S, Ma Z, et al. Strength of PD-1 signaling differentially affects T-cell effector functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:E2480-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Karwacz K, Bricogne C, MacDonald D, et al. PD-L1 co-stimulation contributes to ligand-induced T cell receptor down-modulation on CD8+ T cells. EMBO Mol Med 2011;3:581-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Naramura M, Jang IK, Kole H, et al. c-Cbl and Cbl-b regulate T cell responsiveness by promoting ligand-induced TCR down-modulation. Nat Immunol 2002;3:1192-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang H, Jeon MS, Liao L, et al. K33-linked polyubiquitination of T cell receptor-zeta regulates proteolysis-independent T cell signaling. Immunity 2010;33:60-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fang D, Liu YC. Proteolysis-independent regulation of PI3K by Cbl-b-mediated ubiquitination in T cells. Nat Immunol 2001;2:870-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Crespo J, Sun H, Welling TH, et al. T cell anergy, exhaustion, senescence, and stemness in the tumor microenvironment. Curr Opin Immunol 2013;25:214-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chou JP, Effros RB. T cell replicative senescence in human aging. Curr Pharm Des 2013;19:1680-98. [PubMed]

- Rathmell JC, Vander Heiden MG, Harris MH, et al. In the absence of extrinsic signals, nutrient utilization by lymphocytes is insufficient to maintain either cell size or viability. Mol Cell 2000;6:683-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patsoukis N, Bardhan K, Chatterjee P, et al. PD-1 alters T-cell metabolic reprogramming by inhibiting glycolysis and promoting lipolysis and fatty acid oxidation. Nat Commun 2015;6:6692. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jaudszus A, Gruen M, Watzl B, et al. Evaluation of suppressive and pro-resolving effects of EPA and DHA in human primary monocytes and T-helper cells. J Lipid Res 2013;54:923-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tkachev V, Goodell S, Opipari AW, et al. Programmed death-1 controls T cell survival by regulating oxidative metabolism. J Immunol 2015;194:5789-800. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boussiotis VA. Molecular and Biochemical Aspects of the PD-1 Checkpoint Pathway. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1767-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Taube JM, Anders RA, Young GD, et al. Colocalization of inflammatory response with B7-h1 expression in human melanocytic lesions supports an adaptive resistance mechanism of immune escape. Sci Transl Med 2012;4:127ra37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Parsa AT, Waldron JS, Panner A, et al. Loss of tumor suppressor PTEN function increases B7-H1 expression and immunoresistance in glioma. Nat Med 2007;13:84-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2012;12:252-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ribas A, Shin DS, Zaretsky J, et al. PD-1 Blockade Expands Intratumoral Memory T Cells. Cancer Immunol Res 2016;4:194-203. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liechtenstein T, Perez-Janices N, Blanco-Luquin I, et al. Anti-melanoma vaccines engineered to simultaneously modulate cytokine priming and silence PD-L1 characterized using ex vivo myeloid-derived suppressor cells as a readout of therapeutic efficacy. Oncoimmunology 2014;3:e945378. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Karwacz K, Arce F, Bricogne C, et al. PD-L1 co-stimulation, ligand-induced TCR down-modulation and anti-tumor immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology 2012;1:86-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Curtsinger JM, Lins DC, Mescher MF. Signal 3 determines tolerance versus full activation of naive CD8 T cells: dissociating proliferation and development of effector function. J Exp Med 2003;197:1141-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shin DS, Zaretsky JM, Escuin-Ordinas H, et al. Primary Resistance to PD-1 Blockade Mediated by JAK1/2 Mutations. Cancer Discov 2017;7:188-201. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2443-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, et al. PD-1 Blockade in Tumors with Mismatch-Repair Deficiency. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2509-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang L, Conejo-Garcia JR, Katsaros D, et al. Intratumoral T cells, recurrence, and survival in epithelial ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2003;348:203-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]