Temporal trends and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction in patients with cancer

Introduction

Recent advances in cancer therapy have led to a significant decline in cancer-related mortality. It is estimated that there would be around 18 million cancer survivors in the United States by 2020 (1). Improvement in life expectancy in cancer patients, however, has led to an increase in burden of cardiovascular disease in this cohort of patients, partly related to comorbidities and partly due to the use of cardio toxic chemotherapeutic regimens. This has led to the inception of cardio-oncology, with many centers developing subspecialty programs to cater to the growing need of these patients. However, the exclusion of cancer patients from cardiovascular clinical trials and heart disease patients from oncology investigations has resulted in a paucity of data to direct clinical decision-making in many cardio-oncology patients (2). Further, patients with cancer present with multiple comorbidities such as coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia which make incorporation of existing guideline -based treatments challenging. We sought to identify trends in admissions for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), utilization of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and in-hospital outcomes in patients with three common cancers (lung, breast, colon) compared to patients without cancer.

Methods

We used the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) to identify all admissions with ST elevation myocardial infarction (ICD 9 code 410) from the years 2001–2011. The NIS is part of the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality's Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) and is the largest all-payer inpatient care database in the United States, containing data on >7 million hospital stays. It contains data related to hospital admission and discharge from a 20% stratified sample of community hospitals in the United States (3). We used the clinical classification software developed by HCUP to identify the clinical variables for our analyses. Using this dataset, patients with STEMI and a concurrent diagnosis of lung cancer, colon cancer and breast cancer were identified. A cohort of patients admitted for STEMI without any of these cancer diagnoses was identified as the non-cancer group. We evaluated utilization of PCI (angioplasty and/or stenting) and in-hospital outcomes in STEMI patients with various cancers. All statistical analyses were done using SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Results

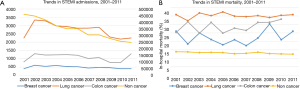

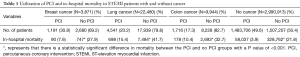

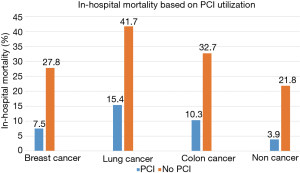

There were 3,794,385 STEMI admissions during the study period from 2001 to 2011 of which 5,552 (0.15%) patients had active breast cancer, 31,246 (0.82%) had lung cancer and 12,015 (0.32%) patients had colon cancer. Trends in STEMI admissions have been declining in the general population and patients with lung cancer, whereas patients with breast and colon cancer demonstrated a stable trend (Figure 1). Utilization of PCI was 30.8% (1,191/3,871), 20.2% (4,541/22,480), and 17.3% (1,716/9,944) in patients with breast, lung and colon cancer, respectively (Table 1). Comparatively, among patients without any of these cancers, use of PCI was 49.5%. In-hospital mortality was highest in patients with lung cancer (57.1%) and lowest in patients without cancer (25.7%) with no significant difference in trends (Figure 1). Utilization of PCI favorably impacted in-hospital mortality in all patients’ groups (Figure 2).

Full table

Discussion

In the present study, we report a significant incidence of STEMI in patients with the three most prevalent cancers in the United States. Although the incidence of STEMI has been declining in the general population, incidence in patients with breast and colon cancer has remained steady. We also report a significant disparity in utilization of PCI in patients with cancer presenting with STEMI compared to the general population. Overall in-hospital mortality was substantially higher in patients with cancer compared to the non-cancer cohort. Even in the cancer cohort, utilization of PCI had a substantial impact on immediate outcomes with higher rates of in-hospital mortality in patients in whom PCI was deferred. This could represent a wide practice variation in the implementation of life saving therapies in patients with cancer.

Coronary artery disease is a frequent comorbidity in patients with various cancers. This is explained partly by the improvement in therapeutic modalities for cancer that prolong life expectancy and in part by direct cardiac and vascular toxic effects of chemotherapy and radiation. In addition, cancer patients have a hypercoagulable state that predisposes to acute thrombotic events. Data on outcomes of cancer patients with STEMI is sparse due to the exclusion of these patients from randomized clinical trials. A few existing registry studies have reported higher mortality rates in patients with cancer presenting with acute coronary syndrome. Velders et al. reported a multi-center study from the Netherlands on outcomes of STEMI in patients with cancer (4). In this prospective registry, patients with cancer had a higher incidence of cardiovascular comorbidities such as peripheral vascular disease, renal insufficiency and cerebrovascular disease. Use of drug-eluting stents and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors was significantly lower in patients with cancer. Patients with cancer who had STEMI had significantly higher all-cause mortality at 1-year follow-up compared with those without a history of cancer (in-hospital 9.1% vs. 3.4%, 1-year 17.4% vs. 6.5%). More importantly, this difference in mortality was primarily driven by a higher incidence of cardiac death in cancer patients (in-hospital 8.7% vs. 3.4%, 1-year 10.7% vs. 5.4%). The presence of cancer, specifically diagnosed in 6 months preceding the STEMI, was an independent risk factor for increased cardiac and all-cause mortality at 7 days on multivariate analysis (adjusted hazard ratio =3.34; 95% CI, 1.57–7.08). In a small observational series from Japan, Kurisu et al. compared outcomes of acute MI in patients with and without cancer and showed no difference in coronary revascularization, discharge medications, stent selection or cardiovascular outcomes between the two groups (5). Yusuf et al. reported a single center experience outcomes of 456 cancer patients with an acute coronary syndrome (STEMI 15%) over a 6-year study period (6). In their series, PCI was utilized in only 3.3% of cancer patients, and the 1-year mortality was 78% in patients with STEMI (6).

Patients with active cancer presenting with STEMI represent a challenging cohort. Complications related to the underlying cancer such as coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, anemia, organ dysfunction, and anticipation of other therapeutic procedures factor into clinical decision making. Patients with advanced cancer are particularly challenging as long-term goals of care have to be considered. In a recent expert consensus statement on the management of cancer patients in the catheterization lab, it was recommended to consider PCI in cancer patients with STEMI and high risk non-STEMI even when life expectancy is <1 year and to use drug-eluting stents if the platelet count is above 30,000/mL (7). In addition to prolonging survival, revascularization may also be a palliative option to control symptoms in patients with severe angina pectoris.

Our study is the largest one reporting contemporary outcomes of STEMI in cancer patients. Strengths of our study include analysis of a nationwide cohort over a decade and a large sample size. However, we acknowledge several limitations. Data on cancer stage, treatment strategies, hematological parameters, and anticipated procedures were not available. All these factors may play a significant role in decision making regarding PCI. We assessed only in-hospital mortality, and data on long-term outcomes were unavailable.

In summary, we report a relatively lower rate of PCI utilization in cancer patients with STEMI. With lack of clinical trial data on management of STEMI in patients with various cancers and with improvements in cancer survivors overall, further studies are required to identify gaps in knowledge in appropriate selection of cancer patients for PCI.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer and disease statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:5-29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barac A, Murtagh G, Carver JR, et al. Cardiovascular health of patients with cancer and cancer survivors: a roadmap to the next level. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:2739-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Steiner C, Elixhauser A, Schnaier J. The healthcare cost and utilization project: an overview. Eff Clin Pract 2002;5:143-51. [PubMed]

- Velders MA, Boden H, Hofma SH, et al. Outcome after ST elevation myocardial infarction in patients with cancer treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol 2013;112:1867-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kurisu S, Iwasaki T, Ishibashi K, et al. Comparison of treatment and outcome of acute myocardial infarction between cancer patients and non-cancer patients. Int J Cardiol 2013;167:2335-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yusuf SW, Daraban N, Abbasi N, et al. Treatment and outcomes of acute coronary syndrome in the cancer population. Clin Cardiol 2012;35:443-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Iliescu CA, Grines CL, Herrmann J, et al. SCAI expert consensus statement: evaluation, management, and special considerations of cardio-oncology patients in the cardiac catheterization laboratory (endorsed by the cardiological society of india, and sociedad Latino Americana de Cardiologıa intervencionista). Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2016;87:E202-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]