The learning curve associated with intracranial angioplasty and stenting: analysis from a single center

Introduction

Intracranial artery stenosis (IAS) is the most common vascular lesion in patients with cerebrovascular disease in China (1). The earlier Chinese intracranial atherosclerosis trial revealed a prevalence of 46.6% in China. Symptomatic patients with IAS also have a high risk of subsequent stroke within one year. Intracranial angioplasty and stenting remains the primary course of treatment for patients with severe IAS who have failed to respond to standard medical therapy (2). However, the stenting and aggressive medical management for preventing recurrent stroke and intracranial stenosis (SAMMPRIS) trial showed a high complication rate (14.7%) within 30 days of angioplasty and stenting treatment (3). The SAMMPRIS trial also revealed an interesting point: the complication rate varied extensively when compared between centers with a large number of patients and centers with only a few patients. This may indicate that one of the factors responsible for this high complication rate was due to the experience of the operator. Recent studies have shown that increased operator experience could help to reduce the rate of complications associated with surgical procedures (4).

In this study, we investigated the role of the operator’s learning curve as a factor in the safety of intracranial angioplasty and stenting. We did this by analyzing data from 329 consecutive patients in a single center. In addition, we identified the number of cases required to overcome the learning curve effect for intracranial angioplasty and stenting.

Methods

Patients and clinical information

As this study was based on a retrospective analysis of cases from a single center, our local regulatory committees did not require us to have specific ethical approval. Patients diagnosed with symptomatic severe IAS and treated with intracranial angioplasty and stenting between January 2007 and December 2015 were recruited in accordance with the following inclusion criteria:

- severe stenosis was defined as stenosis of ≥70% in the internal carotid artery (ICA), the first segment of the middle cerebral artery (M1), the intracranial vertebral artery, or the basilar artery (BA), as measured by criteria provided by the Warfarin versus Aspirin for Symptomatic Intracranial Disease (WASID) study using digital subtraction angiography (DSA) (5);

- treated by intracranial angioplasty and stenting;

- failure to respond to standard medical therapy for recurrent ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA);

- location of the stenosis corresponding to the vascular territory of the ischemic event;

- baseline modified Rankin Scale score ≤2;

- hypo-perfusion substantiated by computed tomography (CT) perfusion.

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

- patients with combined extracranial artery stenosis or aneurysm;

- contraindication to antiplatelet therapy;

- stenosis not caused by atherosclerosis, such as inflammation or Moya disease.

For each patient, we collected the following clinical information: age, gender, history of hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, index events (such as TIA or ischemic stroke in the area of the artery with stenosis), and the time interval from index events to the surgical procedure. Procedure-related variables included the severity of stenosis, anesthesia, location of the lesion, Mori classification of the lesion, perforators (defined as the vessel segment of the lesion with perforators originating from it), double stents for one lesion, treatment options, and procedure failure (6,7). All operators in this study had an experience of more than 20 procedures of extracranial artery stenting in our center. Operator-related variables included operators and operative experience (defined as each individual operator’s case sequence number; the operative sequence was divided into three levels: 1–20, 21–40 and >40 cases) (8).

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint was peri-procedural complications within 30 days. Complications included the following events: TIA (defined as any new neurological event with complete recovery within 24 h); ischemic stroke in the territory of vascular lesions during the follow-up period (substantiated by diffusion weighted imaging); technical problems during the procedure (defined as any technical situation that significantly affected the success of angioplasty and stenting procedures); cerebral hyper-perfusion syndrome (diagnosed as the occurrence of ipsilateral headache, seizures, or a focal neurological deficit without radiographic evidence of infarction); and hemorrhagic events such as vessel perforation or intracranial hemorrhage caused by hyper-perfusion after the procedure or in response to medicine.

Treatment procedure

Aspirin (100 mg/day) and clopidogrel (75 mg/day) were administered for at least 3 days prior to treatment. The same dose of aspirin and clopidogrel was recommended for 3 months after treatment, followed by an indefinite dose of aspirin only (9). Low molecular weight heparin was given for 3 days after stenting. Two kinds of stents were used in our center; initially the Apollo Stent [MicroPort Medical (Shanghai), Shanghai, China] was used, and then, the Wingspan (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) was used from 2009 to the end of study. The procedure was performed under general anesthesia with full heparinization. A 6-French Envoy guiding catheter (Cordis, Miami Lakes, FL, USA) was placed into the distal portion of the internal carotid or vertebral artery. Next, a 0.014-inch micro-guidewire was carefully navigated through the stenosis. Angioplasty and stenting were performed, following the instructions carefully. The choice of stent type was made by the operator, taking into account the patient’s wishes. The criteria for size selection were described previously (10). Systolic blood pressure was monitored and controlled at levels of 120 mmHg for 24 h after treatment (11). If any neurological deteriorations occurred, then an appropriate form of imaging was carried out to investigate for potential complications. Noncontrast CT was performed for every patient at 24 h after the treatment, even if patients did not show any neurological deterioration.

Outcome assessment

Details of all technical problems arising during the surgery were recorded by the operator. Peri-procedural neurological deterioration at 30 days after treatment was recorded by a neurosurgeon who was not involved in the study and was blinded to clinical information. The same neurosurgeon used appropriate imaging techniques to confirm the presence of ischemic or hemorrhagic complications if patients experienced neurological deterioration at any point during the study.

Statistical analysis

Operator experience was divided into three different levels: 1–20, 21–40 or >40 cases, according to the operation sequence (8). All variables associated with peri-procedural complications were analyzed by univariate logistic regression. Variables with a P value <0.2 were used for subsequent multivariable logistic regression to evaluate the risk factors associated with peri-procedural complications. A second multivariate logistic regression model that excluded operator experience was used to evaluate the probability of peri-procedural complications for each case and was then used to construct an RA-CUSUM chart to evaluate caseload. Two-sided P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed with the use of SAS 9.4.

Results

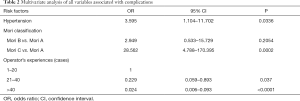

In total, 359 patients were diagnosed in our center between January 2007 and December 2015 with severe IAS and treated with angioplasty and stenting. Of these, 28 patients were excluded due to the additional presence of extracranial artery stenosis (23 patients) or cerebral aneurysm (5 patients). Two more patients were also excluded because they did not have any follow-up data. Finally, 329 patients with 329 intracranial lesions were included in the final analysis. There were 244 males and 85 females (mean age: 55.9±10.2 years; median 52 years; range, 26–81 years) who presented with stroke (n=70) or TIA (n=259). Of these, 193 patients had hypertension, 78 had diabetes, and 79 had hyperlipoidemia. The median modified Rank Scale score was 1, and the mean degree of stenosis was 85.7±7.0% (median: 85%; range, 70–99%). Lesions were located in the intracranial ICA in 26 cases (7.90%), the M1 in 170 cases (51.67%), the BA in 82 cases (24.92%), and intracranial vertebral artery in 51 cases (15.50%). The event-to-stenting interval was ≤21 days in 139 patients (42.25%) and >21 days in 190 patients (57.75%). Of these patients, 60 patients were classified as Mori A type, 158 as Mori B type, and 111 as Mori C type. Four lesions were treated with double stents because the lesion length was ≥12 mm or the lesion was not completely covered by the first stent; In this study, these circumstances were classified as one procedure. Univariable logistic regression results revealed stenosis location, Mori classification and operator experience associated with the complications (Table 1).

Full table

Peri-procedural complications and risk factors

The overall rate of 30-day peri-procedural complications was 8.2% (27/329). Eighteen cases involved ischemia, while nine cases involved hemorrhagic complications. Seven of these patients died due to their complications. Multivariable logistic regression indicated that a history of hypertension [odds ratio (OR) =3.595; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.104–11.702] was a risk variable associated with peri-procedure complications. Compared with Mori classification A, Mori classification C (OR =28.562; 95% CI: 4.788–170.395) increased the risk of peri-procedure complications (Table 2).

Full table

Operator experience was significantly correlated with peri-procedure complications. Adjusting for other variables, operators with more than 20 cases worth of experience were associated with a level of protection that led to a reduced risk of peri-procedure complications (OR =0.229; 95% CI: 0.059–0.893). Furthermore, compared with operator experience of less than 20 cases, operators with more than 40 cases worth of experience also showed a reduced level of risk for complications with a lower odds ratio (OR =0.024; 95% CI: 0.006–0.093).

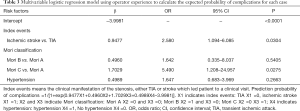

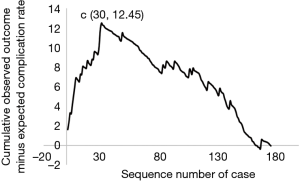

To evaluate the learning curve for intracranial angioplasty and stenting, the expected probability of complications for each individual case was calculated with a second multivariate logistic regression model (Table 3). The calibration of the model was good, as shown by the Hosemer-Lemeshow method (χ2=0.0136; P=0.9996). The learning curve of IAS was demonstrated by a risk-adjusted CUSUM chart (Figure 1). Visual inspection of the RA-CUSUM chart demonstrated that the observed outcome was worse than expected (more positive deflections) at the beginning of the series. The observed outcome was better than expected (more negative deflections) after the 30th consecutive case. However, patient characteristics before and after the 30th case were not different, although the proportion of Mori type was higher in cases after the 30th case (Table S1). This suggests that the learning curve for intracranial angioplasty and stenting to overcome complications in a risk-adjusted manner is 30 cases.

Full table

Full table

Discussion

In this study, we found that the rate of complications of intracranial angioplasty and stenting decreased as the operators’ case number increased. In addition, we found there was a learning curve for intracranial angioplasty and stenting. The number of cases required to overcome this learning curve effect for intracranial angioplasty and stenting in our center was calculated to be 30 cases.

A recent study revealed that the prevalence of IAS in China is high (12). The WASID trial further demonstrated that symptomatic patients with severe IAS are considered to have a 20% risk of stroke in 1 year (13). Intracranial angioplasty and stenting remains the primary course of treatment for patients with severe IAS who fail to respond to medical therapy. However, the SAMMPRIS trial showed disappointing results in that angioplasty and stenting could lead to a higher complication rate compared with patients treated with standard medical therapy. In our study, the proportion of peri-procedure complications was only 8.2%, compared with 14.7% in the SAMMPRIS trial. This indicated that intracranial angioplasty and stenting may represent a favorable treatment for severe symptomatic IAS. The mean age of patients in the present study was lower than the mean age in the SAMMPRIS trial (59.5±11.8 years); therefore, our data may indicate that patients with IAS are slightly younger than foreign patients.

The reasons for the low ratio of peri-procedure complications in our center may be ascribed to a variety of different factors. First, this could be due to our operators having significant experience. In the SAMMPRIS trial, operators in the participant centers were required to have experience of at least 20 consecutive intracranial stent or angioplasty cases, including a minimum of three Wingspan cases (3). Therefore, the investigators concluded that the high proportion of peri-procedure complications involving angioplasty and stenting was not caused by inexperience. However, our study showed that the volume of cases required to overcome the learning curve effect of intracranial angioplasty and stenting in our center was 30. We also found that the complication rate decreased as operator experience increased. When operators had less than 20 cases worth of experience, the ratio of peri-procedure complications was 27.5%; however, this ratio decreased to 15.0% when operators had experience of 21–40 cases and to 4.0% when operators had experienced more than 40 cases. These results indicate that the inclusion criteria for the operators in the SAMMPRIS trial may not have been appropriate.

Second, we need to consider blood pressure monitoring and control. Our study showed that hypertension correlated with peri-procedure complications. Previous studies found a relationship between hypertension and hyperperfusion after intracranial angioplasty (9). A long history of hypertension could lead to depolarization of the vascular smooth muscles and vasoconstriction of the small arterioles. After intracranial angioplasty and stenting, cerebral vessels may not adapt to the increased blood perfusion, thus leading to a disastrous complication. In our center, 24-hour blood pressure monitoring was implemented for every patient, and blood pressure was controlled under 120 mmHg after treatment. This may represent one of the factors responsible for the low proportion of peri-procedure complications.

Third, only 33.7% of patients were classified as having Mori C stenosis. Mori classification is a proven predictor of outcome and restenosis after intracranial angioplasty and stenting (5). In our present study, only 33.7% (111/329) of cases were classified as Mori C type. However, the complication rate was 15.3% (17/111) in this particular subgroup. This may indicate that Mori classification played an important role in peri-procedure complications during intracranial angioplasty and stenting. Cases with Mori A lesions tend to have a lower risk of peri-procedure complications than Mori B and Mori C lesions. Compared with Mori A, Mori B and Mori C cases are associated with long, more eccentric and wide-angle stenosis, which may lead to a high rate of complications during angioplasty and stenting. This result may indicate that operators with only limited experience should begin their training on cases classified as Mori A type.

There are some limitations to our study that need to be considered. First, this was a retrospective study; in order to avoid complications, several patients with Mori C type and old age may not have been advised to receive angioplasty or stenting. Furthermore, after 2014, we used high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging techniques to select patients with a low risk of complications; this practice led to the development of strict inclusion criteria which reduced the risk of complications (7). Second, all treatments were carried out by only two operators. It is possible that the learning curve may be different for other operators. Previous studies found that age and diabetes, as well as Mori classification and hypertension, were also risk factors for complications during intracranial angioplasty and stenting. However, we did not identify other risk factors after multivariable logistic analysis, although this may have been because of the limited sample size of patients. Moreover, the overall number of patients with complications was only 27. Consequently, this may have resulted in some important variables being left out of our logistic regression models. With the help of high-resolution MRI, we can purposefully select patients with a low risk of complications. Finally, the amount of experience considered sufficient for performing IAS was identified as 30 cases; this could represent important inclusion criteria for centers to participate in clinical trials.

Conclusions

The amount of experience gained by an operator could influence the rate of peri-procedure complications following intracranial angioplasty and stenting. The number of cases required to overcome this learning curve effect for intracranial angioplasty and stenting in our center was calculated to be 30.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: As this study was based on a retrospective analysis of cases from a single center, our local regulatory committees did not require us to have specific ethical approval.

References

- Wang Y, Zhao X, Liu L, et al. Prevalence and outcomes of symptomatic intracranial large artery stenoses and occlusions in China: the Chinese Intracranial Atherosclerosis (CICAS) Study. Stroke 2014;45:663-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bai WX, Gao BL, Li TX, et al. Wingspan stenting can effectively prevent long-term strokes for patients with severe symptomatic atherosclerotic basilar stenosis. Interv Neuroradiol 2016;22:318-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Derdeyn CP, et al. Stenting versus aggressive medical therapy for intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med 2011;365:993-1003. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yu SC, Leung TW, Lee KT, et al. Learning curve of Wingspan stenting for intracranial atherosclerosis: single-center experience of 95 consecutive patients. J Neurointerv Surg 2014;6:212-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhu SG, Zhang RL, Liu WH, et al. Predictive factors for in-stent restenosis after balloon-mounted stent placement for symptomatic intracranial atherosclerosis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2010;40:499-506. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yu SC, Leung TW, Hung EH, et al. Angioplasty and stenting for intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis with nitinol stent: factors affecting technical success and patient safety. Neurosurgery 2012;70:104-13. [PubMed]

- Banerjee C, Chimowitz MI. Stroke Caused by Atherosclerosis of the Major Intracranial Arteries. Circ Res 2017;120:502-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cai Q, Li Y, Xu G, et al. Learning curve for intracranial angioplasty and stenting in single center. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2014;83:E94-100. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xu S, Wu P, Shi H, et al. Hyperperfusion Syndrome After Stenting for Intracranial Artery Stenosis. Cell Biochem Biophys 2015;71:1537-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jiang WJ, Xu XT, Jin M, et al. Apollo stent for symptomatic atherosclerotic intracranial stenosis: study results. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2007;28:830-4. [PubMed]

- Abou-Chebl A, Reginelli J, Bajzer CT, et al. Intensive treatment of hypertension decreases the risk of hyperperfusion and intracerebral hemorrhage following carotid artery stenting. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2007;69:690-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gao P, Zhao Z, Wang D, et al. China Angioplasty and Stenting for Symptomatic Intracranial Severe Stenosis (CASSISS): A new, prospective, multicenter, randomized controlled trial in China. Interv Neuroradiol 2015;21:196-204. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Howlett-Smith H, et al. Comparison of warfarin and aspirin for symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1305-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]