Changing reimbursement models and private equity ownership in spine surgery

Introduction

The increasing cost of healthcare has been an ongoing problem in the United States, placing unnecessary strain on both patients and providers alike. In 2017, 17.9% of the United States gross domestic product (GDP), roughly 3.5 trillion dollars, was spent on the healthcare sector. This large percentage of increasing healthcare costs is projected to be 19.4% of the nation’s GDP by the year 2027—reflecting a 5.5% annual increase in healthcare expenditure (1). From this subset of healthcare expenses, $90 billion is spent on the management of low back pain each year—a number which is expected to grow disproportionately as the general population ages and lives longer (2). While there are numerous factors contributing to the rising summation of healthcare costs, the fee-for-service reimbursement model is arguably one of main culprits. Critics contend that this payment structure leads to wasteful spending and an inappropriate use of resources, with questionable improvement in quality at best. Therefore, in an effort to reduce overall costs and simultaneously increase the quality of care delivered, newer reimbursement models, such as the bundled payment model, has been proposed and more widely adopted. Met with widespread enthusiasm, implantation of bundled payments has risen across all specialties of medicine, including spine surgery, and may eventually result in long-term changes in the structure of orthopaedic and neurosurgical spine practices. The transition from fee-for-service to bundled payments may also have a powerful effect on private equity investments in orthopaedic surgery and in spine surgery more specifically. As orthopaedic practices continue to be a target among private equity firms, the institution of bundle payments will undoubtedly play a role in investment strategy for potential buyers.

Models of reimbursement

Currently, the fee-for-service model is the dominant reimbursement structure within the medical field in the United States (3,4). In this model, healthcare providers are reimbursed separately for every portion of the care administered, including office visits, diagnostic test, and interventions. By allowing each aspect of care to be reimbursed regardless of cost, quality, or outcome, or in any many cases need, the fee-for-service model has been criticized for indirectly incentivizing providers to overuse resources and, in some instances, subject patients to frivolous treatments and unnecessary interventions. Consequently, the fee-for-service model has been proposed to be one of the main perpetrators behind the aforementioned rise in national healthcare associated costs, as payment in this model is dependent on the quantity, not quality, of care delivered (3,4).

In the bundle- service model, one payment, adjusted for regional variation and other factors, is assigned to all procedures and the ancillary services (e.g., diagnostic imaging, physical therapy, etc.), and potential complications that may occur over the course of an episode of care. The bundled payment model places greater financial responsibility on the provider for controlling the costs of healthcare for each episode of care. This model has become increasingly popular because of its theoretical ability to reduce costs and unnecessary spending while improving quality of care. Providers are financially incentivized to improve outcomes, decrease length of stay, and promote a multi-disciplinary approach to medical care.

From fee-for-service to bundled payments in spine surgery

In the era of value-based care, more and more institutions have transitioned towards bundled payments. In a survey of 24 stakeholders across 12 organizations that perform approximately 12,000 spine surgeries annually, Kazberouk et al. discovered that 8 of these organizations had already implemented bundled payment initiatives. Although the traditional fee-for-service reimbursement model still covers the majority of patients treated at these organizations, the number of spine patients covered by bundled payments was expected to increase by roughly 30–45% over the course of 3 years (3). In practice, bundled payments will force surgeons to take on greater financial risks as negative patient factors such as medical comorbidities, which are known to have an effect on outcomes and complications, can affect the bottom-line (4,5). Surgeons may also be under pressure to cut costs by eliminating certain diagnostic tests and altering lengths of stay, potentially resulting in sub-par medical care and loss of physician autonomy. Large institutions attempt to balance this conundrum through multiple alignment strategies termed “gainsharing” and “co-management arrangements” (6). Both gainsharing and co-management arrangements incentivize the surgeon to accept these bundled payment restrictions. Gainsharing allows for a surgeon to share in the cost savings that are generated for the institution, assuming that the clinical care was not adversely affected (7). However, there are currently limitations with gainsharing. First, based on a series Office of Inspector General opinions, it is extremely difficult to legally gainshare (8). Second, even if gainsharing was performed legally, there is a cap set on the amount of the savings that can be shared with the surgeons, regardless of their caseload and quality of care rendered. As a result, a surgeon with a high caseload who demonstrates superior outcomes would be entitled to the same and limited financial gains as a surgeon with fewer cases who demonstrates average outcomes (6).

The second alignment strategy is called a co-management arrangement (6). In this strategy, the institution gives greater administrative and business management responsibilities to the surgeon. However, such responsibilities and their implementation are often in the context of a timely, complex administrative system within the hospital, stripping the surgeons from time for patient care.

An opportunity for private equity with the emergence of bundled payments

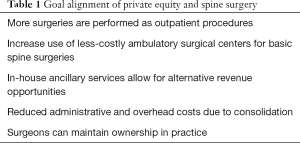

With the rise of value-based care, efforts to reduce inefficient cost structures through consolidation provides unique goal alignment between private equity firms and spine surgery practices (Table 1). Private equity firms are alternative investment vehicles that raise capital through limited partners, such as pensions funds, University Endowments, and wealthy individuals. The firm will take the committed capital and invest it through a leverage buyout, a strategy where a relatively high level of debt is used (50–70%) during the acquisition, allowing the private equity firm to invest less equity while still obtaining control of a business. Once in control of the company, a private equity firm attempts to improve the business to raise the business’s value while paying off debt to increase the firm’s equity in the company. Ideally in 3–5 years, the firm hopes to sell the company, leading to high returns (15–20% returns annually on the initial investment). To increase returns, firms will often attempt to improve earnings of their portfolio companies by two core strategies: reducing operating costs and increasing revenue. Consolidation is one of the most effective ways for private equity firms to accomplish these goals quickly.

Full table

A key component of an effective private equity target is stable, recurring cash flow, which allow for liquidity to pay off the debt and its accompanying interest payments. Current trends in spine surgery coincide with these fundamental characteristics. Due to improved technology and minimally invasive surgery, spine procedures that were traditionally inpatient are becoming increasingly outpatient, substantially reducing costs (9). Furthermore, in a move to adopt bundled payment reimbursements for spine surgery, there will be an impetus for spine centers to perform certain elective procedures with well-defined indications and outcomes in less-costly ambulatory surgical centers (ASCs) with 23-hour observation units. Spine procedures performed at an ASC have been shown to be less expensive than the same procedure performed at an acute care hospital (10). By investing in a practice and increasing the cases performed at ASCs, a private equity firm can quickly improve their margins. Arguably the most attractive aspect of orthopedic practices for private equity firms is the opportunity of less invasive ancillary services, such as medical imaging, physical therapy, and sports medicine. Ancillary services not only provide practices with an in-house complement to surgery for bundled payment reimbursements purposes, but also offer an entirely new business opportunity that circumvents bundled payments altogether (11).

For spine surgeons, there are a number of possible benefits working in the confines of a private equity-based ownership. Physicians can receive an initial payment by selling off equity. They may also be more likely to retain some ownership (12). Without the restrictions of hospital-based gainsharing and the limited individual impact of a co-managerial arrangement, the surgeon and the group retain the optimal components of their current practice patterns and overall dedication to patient care. Private equity also offers the unique opportunity for physicians and practices to enter into a growth model by providing both financing and the expertise of merging smaller, previously independent practices. As a result, there is both immediate reductions in redundant administrative and overhead costs and possible implementation of new modes of business through noninvasive treatment options. Moreover, the consolidation of smaller practices provides more leverage in contract negotiations with health insurance companies for reimbursement.

However, there are drawbacks to private equity ownership. For starters, physicians need to be careful in finding the proper private equity partner who is capable of balancing financial returns with effective healthcare delivery. Additionally, it is not uncommon for firms to buy companies and quickly replace the preexisting management team. If everything goes to plan, the primary goal of the private equity firm is to depart from a company within 5 years, which makes one question how the quick turnover in ownership may impact the long-term outcome of the previously owned practice. When it is time to sell, the practice may land in the hands of a large health organization or possibly another private equity firm, who could decide to take the practice in a completely new direction.

While it is difficult to predict what changing reimbursement models and private equity involvement in spine surgery will bring, the current trends have shown that a transformation is truly underway. The ultimate goal is to provide a healthcare environment that incentivizes providers and payers to give high-quality and cost-effective care, while ensuring that the healthcare experience of the patient is continually improved.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Medicare C for, Baltimore MS 7500 SB, Usa M. NHE-Fact-Sheet. Available online: https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata/nhe-fact-sheet.html

- Davis MA, Onega T, Weeks WB, et al. Where the United States Spends its Spine Dollars: Expenditures on different ambulatory services for the management of back and neck conditions. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012;37:1693-701. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kazberouk A, McGuire K, Landon BE. A Survey of Innovative Reimbursement Models in Spine Care. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2016;41:344-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rossi VJ, Ahn J, Bohl DD, et al. Economic factors in the future delivery of spinal healthcare. World J Orthop 2015;6:409-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hussey PS, Ridgely MS, Rosenthal MB. The PROMETHEUS bundled payment experiment: slow start shows problems in implementing new payment models. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:2116-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Scalise J, Jacofsky D. Payor Reform Opportunities for Spine Surgery: Part II: The Potential Emergence of Population Health. Clin Spine Surg 2018;31:261-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gainsharing Arrangements and CMPs for Hospital. Available online: https://www.oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/alertsandbulletins/gainsh.htm

- OIG Advisory Opinion 17-09. 14. Available online: https://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/advisoryopinions/2017/AdvOpn17-09.pdf

- Bannow T. Private equity interest in orthopedic practices expected to balloon. Modern Healthcare. Available online: https://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20181008/NEWS/181009913/private-equity-interest-in-orthopedic-practices-expected-to-balloon

- Robinson JC, Brown TT, Whaley C, et al. Consumer Choice Between Hospital-Based and Freestanding Facilities for Arthroscopy: Impact on Prices, Spending, and Surgical Complications. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2015;97:1473-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Provident Healthcare Partners. Private Equity Investment in Orthopedics. Available online: https://www.providenthp.com/provident-perspectives-private-equity-investment-in-orthopedics/. Published 2015.

- Gooch K. Why large physician groups should consider private equity. Becker’s Hospital CFO Report. Available online: https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/finance/why-large-physician-groups-should-consider-private-equity-5-thoughts-with-todd-mello.html. Published 2018.