Impact of prior cancer on outcomes in nasopharyngeal carcinoma

Introduction

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a head and neck cancer common in South China and Southeast Asia (1). With the primary treatment of radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy, the 5-year overall survival (OS) of early stage NPC is greater than 90% (2). However, recurrent or primary metastatic NPC still represents a critical unmet medical need in oncology research. Despite the ability of intensity-modulated radiation therapy to significantly improve the tumor local control rate, distant metastasis is still poorly controlled, which remains the major reason for treatment failure. Many large clinical trials have been conducted to find the optimum comprehensive therapy for these patients in order to improve survival, which includes the standard first-line treatment option, gemcitabine plus cisplatin, and induction chemotherapy plus concurrent chemoradiotherapy (3,4).

Clinical trials are essential for better management of these patients. Fewer than 5% of adults with cancer in the United States participate in clinical trials (5). Clinical trial eligibility criteria present a major barrier to the study’s enrollment, especially in oncology clinical trials, where patients with a prior cancer diagnosis are frequently excluded (6). For instance, over 80% of lung cancer trials sponsored by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) exclude patients with prior cancer (7). This practice is mainly based on the long-held assumption that prior cancer diagnosis and treatment could interfere with study outcomes. However, our previous pan-cancer study suggested that not all prior cancers actually interfere with study outcomes (8). The number of cancer survivors has had a four-fold increase in the United States over the last three decades (9). Due to the improved survival of cancer patients, the prevalence of multiple primary cancer has also increased rapidly (10). Twenty-five percent of older adults and more than 10% of younger adults diagnosed with cancer have a history of prior cancer (11). Given the increased number of cancer survivors, the impact of this exclusion criteria will likely increase.

Until now, no study has specifically evaluated the impact of prior cancer on NPC outcomes, and little is known about the characteristics of NPC patients with prior cancer. There is also no available database report in South China and Southeast Asia yet. To address this absence in data, we identified the characteristics and determined the prognostic impact of prior cancer among patients with NPC using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database.

Methods

Data source and population

We extracted data from the SEER database by using the SEER*Stat software version 8.3.5, which covers approximately 30% of the population in the United States (https://seer.cancer.gov/, accession number: 13693-Nov2015) (12,13).

The study population included patients diagnosed with NPC from January 2004 to December 2009. Patients who met any of the following criteria were excluded from the study: (I) age at diagnosis younger than 18 years, (II) patients with only autopsy or death certificate records, and (III) patients with incomplete survival data and follow-up information.

We extracted demographic and clinicopathological data from the SEER database, including sex, age, race, marital status, pathology grade, TNM stage, surgery, and radiotherapy. We classified the race as white, black, and others. Patients were divided into married or unmarried. The TNM stage was based on the AJCC (6th edition) staging system. Considering that the survival data were available in the measurement unit of months, the survival time of 0 months was recorded as 0.5 months to include patients who died within 1 month of diagnosis.

Measures

A history of prior cancer was determined from SEER sequence numbers, as described in our previous study (8). In brief, sequence numbers represent the order of all primary reportable neoplasms diagnosed in a lifetime. The timing of the prior cancer was calculated by using the SEER diagnosis dates of the index cancer and the most recent of any prior cancers. Cases with full timing records were used for further study. The primary outcome of this study was OS. We set December 31st, 2014, as the follow-up cutoff date to ensure that all included cases were followed up for at least 5 years.

Statistical analysis

We categorized patients into two groups based on prior cancer history. Differences in patients’ characteristics were assessed by Pearson chi-squared analysis for categorical variables and t-test for continuous variables as appropriate. In this study, we employed a propensity score matching (PSM) method to minimize the effect of confounding from differences in baseline characteristics (14). Propensity scores were calculated based on race, sex, age, marital status, TNM stage, pathologic grade, and treatment. A one-to-one PSM with a caliper of 0.2 was performed. The characteristics were balanced after PSM. These PSM pairs were used in subsequent analyses.

OS was calculated with the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences were compared using log-rank tests. Finally, we built a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model to identify whether prior cancer impacted the prognosis independently. The common demographic and clinicopathological data, including race, sex, age, marital status, TNM stage, pathologic grade, and treatment, were entered as covariates. Statistical significance was set as a two-sided P value of less than 0.05. Analyses were performed using R Statistical software (version 3.4.2, Institute for Statistics and Mathematics, Vienna, Austria; www.r-project.org).

Results

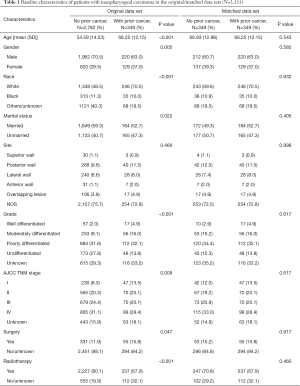

In total, we identified 3,131 eligible NPC patients diagnosed between 2004 and 2009. Among these cases, 11.15% (n=349) had a history of prior cancer. Compared with cases without previous malignancies, patients with prior cancer were older (66.25 vs. 54.59 years, P<0.001), female (37.0% vs. 29.5%, P=0.005), white (70.5% vs. 48.5%, P<0.001), and unmarried (47.3% vs. 40.7%). The percentage of surgery was larger among patients with prior cancer (15.8% vs. 11.9%, P=0.047), and patients with prior cancer received less radiotherapy (67.9% vs. 80.1%, P<0.001). Additional baseline characteristics are displayed in Table 1. Characteristics were balanced between groups after adjustment for propensity score (Table 1, P>0.05). Among 349 NPC patients with a history of cancer, the types of prior cancer were clearly recorded for 225 patients in the SEER database. The most common prior cancers in our study cohort were head and neck (21.78%), prostate (21.33%), gastrointestinal (14.22%), other genitourinary and gynecologic types (13.34%), and breast cancer (9.78%). Localized and regional stages accounted for 77.46% of cases. Over 60.52% of the prior cancers were diagnosed within 5 years of the index NPC. The median time between the most recent prior cancer diagnosis and the index NPC was 3.5 years.

Full table

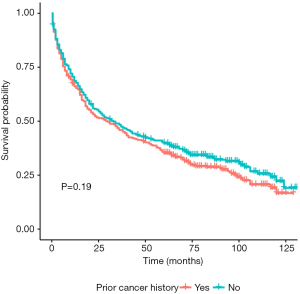

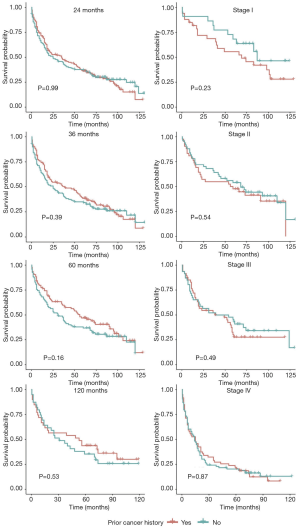

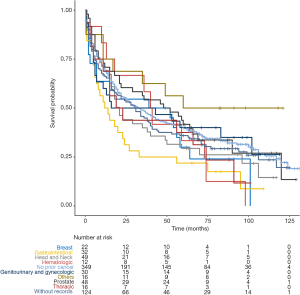

In unadjusted Kaplan-Meier analysis, NPC patients with prior cancer demonstrated similar OS compared to patients without prior cancer (log-rank tests P=0.19) (Figure 1). The overall 5-year survival rates for patients with or without prior cancer were 35.2% [95% confidence interval (CI), 30.5–40.6] and 39.8% (95% CI, 35.0–45.4), respectively. Figure 2 depicts Kaplan-Meier survival curves stratified by the timing of prior cancer and index cancer TNM stage. Subgroup analyses stratified by timing of prior cancer and AJCC TNM stage of index cancer displayed the same tendency; prior cancer did not adversely affect OS compared with patients without prior cancer (P>0.05). Figure 3 shows OS according to prior cancer type. Patients with prior gastrointestinal cancer tend to have inferior survival compared with patients without prior cancer (P=0.008), while other cancer types demonstrate a similar OS.

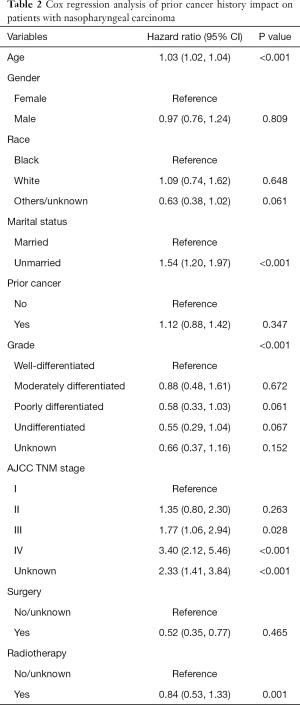

In propensity-score—adjusted Cox models, patients with prior cancer had the same/non-inferior OS [hazard ratio (HR) =1.12, 95% confidence interval, 0.88 to 1.42], compared to patients without a prior cancer (Table 2).

Full table

Discussion

Stringent eligibility criteria for oncology clinical trials can minimize the risks to the participants, but they can also significantly affect the accrual and external validity of a clinical trial (15). In practice, patients with a prior cancer history are usually excluded in cancer clinical trials due to the potential interference of study outcomes. However, there is no authoritative data currently available to support this assumption. Given the sizeable number of cancer survivors, the impact of these criteria will increase, and it is critical to understand the impact of prior cancer. Until now, whether NPC patients with prior cancer faced a worse prognosis had remained unknown; our study was precisely aimed to elucidate this problem. We observed that cases of NPC patients with prior cancer did not result in inferior survival outcomes when compared with those without prior cancer. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the characteristics and prognostic impact of prior cancer among NPC patients. Thus, we need to rethink the long-held assumptions which exclude patients with prior cancer from clinical trials.

Our previous study has mentioned the varying impact of prior cancer according to specific cancer types (8). The novelty in our approach was dividing these cancers into two categories, “prior cancer inferior” (PCI), in which patients had lower survival rates than those without prior cancer; and “prior cancer similar” (PCS), in which survival rates were similar. From this point of view, NPC is one kind of PCS cancer. Several studies also addressed the same questions for other cancer types. Although prior cancer might impact the OS in patients with prostate cancer (16), prior cancer does not contribute to poor survival outcome in many other cancer types, such as in lung, glioblastoma, esophageal, gastrointestinal tract, and pancreatic cancer (17-23). Notably, the impact of prior cancer on early-stage, locally advanced, and advanced lung cancer are consistent, showing a lack of adverse effect on clinical outcomes (17,18,20). Our results also confirmed similar phenomena in the different stages of first-time NPC, which suggests that our findings are applicable to clinical trials for different stages of NPC.

The timing of prior cancer also needs to be fully considered when determining the impact of prior cancer exclusion criteria on clinical trials (24). Generally, a 5-year exclusion window is commonly employed in most trials (7), and over 60% of prior cancers occurred within this window in our study. The median interval between prior cancer and the index NPC was 3.5 years. This information indicates that active surveillance and screening for NPC is necessary for cancer survivors. Subgroup analysis stratified by timing of prior cancer displayed the same tendency: prior cancer did not adversely affect OS. In other words, the impact of prior cancer is independent of timing. From this perspective, NPC patients with prior cancer can be considered for enrollment in trials regardless of timing, and improve accrual without affecting outcomes.

There are, however, several limitations in interpreting our study. Firstly, there is a paucity of detailed characteristics concerning prior cancers diagnosed outside of the registry state, which are recorded in sequence number only. So, our study only focused on the timing of prior cancer. Additionally, the efficacy and tolerability of therapy on prior cancer, which may disrupt the management for the index cancer, cannot be considered due to the data restriction. Secondly, we could not obtain detailed data on treatments and comorbidities from the SEER database. Therefore, neither could comorbidities be matched in our PSM analyses, nor could they be included in the regression models. Thirdly, PSM analysis only accounts for observable covariates, and hidden bias resulted from unobserved confounders that remained after matching. Finally, the data obtained from the SEER database covers only approximately 34.6% of the total U.S. population, thus making it necessary to confirm the generality of our findings.

Conclusions

Among patients with NPC, prior cancer does not convey an adverse effect on clinical outcomes, regardless of the timing of prior cancer and the stage of index cancer. Broader inclusion trial criteria could be adopted in NPC patients with a history of prior cancer. However, further studies are warranted to confirm the appropriateness of this exclusion criterion in NPC trials.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the efforts of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program tumor registries in providing high-quality open resources for researchers.

Funding: National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFC0905500, 2016YFC0905503), Chinese National Natural Science Foundation project (81572659).

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: Institutional review board approval was waived for this study because the SEER database is a public anonymized database. The author, HQ Zhou obtained access to the SEER database (accession number: 13693-Nov2015).

References

- Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 2015;136:E359-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xiao WW, Han F, Lu TX, et al. Treatment outcomes after radiotherapy alone for patients with early-stage nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2009;74:1070-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sun Y, Li WF, Chen NY, et al. Induction chemotherapy plus concurrent chemoradiotherapy versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy alone in locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a phase 3, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:1509-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang L, Huang Y, Hong S, et al. Gemcitabine plus cisplatin versus fluorouracil plus cisplatin in recurrent or metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2016;388:1883-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP. Participation in cancer clinical trials: race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. JAMA 2004;291:2720-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lara PN Jr, Higdon R, Lim N, et al. Prospective evaluation of cancer clinical trial accrual patterns: identifying potential barriers to enrollment. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:1728-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gerber DE, Laccetti AL, Xuan L, et al. Impact of prior cancer on eligibility for lung cancer clinical trials. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014;106. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhou H, Huang Y, Qiu Z, et al. Impact of Prior Cancer History on the Overall Survival of Patients Newly Diagnosed with Cancer: A Pan-cancer Analysis of the SEER Database. Int J Cancer 2018;143:1569-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Moor JS, Mariotto AB, Parry C, et al. Cancer survivors in the United States: prevalence across the survivorship trajectory and implications for care. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2013;22:561-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hayat MJ, Howlader N, Reichman ME, et al. Cancer statistics, trends, and multiple primary cancer analyses from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. Oncologist 2007;12:20-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Murphy CC, Gerber DE, Pruitt SL. Prevalence of Prior Cancer Among Persons Newly Diagnosed With Cancer: An Initial Report From the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. JAMA Oncol 2018;4:832-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Farago AF, Keane FK. Current standards for clinical management of small cell lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res 2018;7:69-79. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Key Statistics for Small Cell Lung Cancer. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/small-cell-lung-cancer/about/key-statistics.html. Accessed 2018/6/13.

- Austin PC. An Introduction to Propensity Score Methods for Reducing the Effects of Confounding in Observational Studies. Multivariate Behav Res 2011;46:399-424. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rothwell PM. External validity of randomised controlled trials: "to whom do the results of this trial apply? Lancet 2005;365:82-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dinh KT, Mahal BA, Ziehr DR, et al. Risk of prostate cancer mortality in men with a history of prior cancer. BJU Int 2016;117:E20-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Laccetti AL, Pruitt SL, Xuan L, et al. Effect of prior cancer on outcomes in advanced lung cancer: implications for clinical trial eligibility and accrual. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015;107. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Laccetti AL, Pruitt SL, Xuan L, et al. Prior cancer does not adversely affect survival in locally advanced lung cancer: A national SEER-medicare analysis. Lung Cancer 2016;98:106-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smyth EC, Tarazona N, Peckitt C, et al. Exclusion of Gastrointestinal Cancer Patients With Prior Cancer From Clinical Trials: Is This Justified? Clin Colorectal Cancer 2016;15:e53-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pruitt SL, Laccetti AL, Xuan L, et al. Revisiting a longstanding clinical trial exclusion criterion: impact of prior cancer in early-stage lung cancer. Br J Cancer 2017;116:717-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zacharia BE, DiStefano N, Mader MM, et al. Prior malignancies in patients harboring glioblastoma: an institutional case-study of 2164 patients. J Neurooncol 2017;134:245-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- He X, Li Y, Su T, et al. The impact of a history of cancer on pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma survival. United European Gastroenterol J 2018;6:888-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saad AM, Al-Husseini MJ, Elgebaly A, et al. Impact of prior malignancy on outcomes of stage IV esophageal carcinoma: SEER based study. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;12:417-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gerber DE, Pruitt SL, Halm EA. Should criteria for inclusion in cancer clinical trials be expanded? J Comp Eff Res 2015;4:289-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]