Clinical trials of yeast-derived β-(1,3) glucan in children: effects on innate immunity

Introduction

More and more studies confirm that environmental pollution is connected to health problems, particularly respiratory problems. The most damaging factors include extreme urbanization, an increase in energy consumption (through pollution from power stations), burning of low quality coal in houses, pollution from petrochemical industry and most of all, an extreme increase of use of motor vehicles (1-4).

North Bohemia still represents the locality with the highest pollution in the middle Europe and the nickname “black spot of Europe” is unfortunatelly still valid. One of the results of these conditions is the high prevalence of various diseases, particularly in children suffering with repeated infections (4), rhinoconjunctivitis, chronic bronchitis, chronic obstructive lung diseases and asthma. In order to improve clinical manifestation of the medical problems mentioned above, two things are necessary: correct diagnosis and the transfer of children from high risk areas into medical facilities localized in environment with minimal environmental stress.

In order to evaluate these effects and the possible effects of glucan treatment, we have long-term cooperation with Sanatorium for Respiratory Diseases Edel, which is located in North Moravia in an area of extremely low airpollution. This Ssanatorium offers not only optimal therapeutic treatment, but also a complexity of additional treatments, including speleotherapy, which is a good addition to climatotherapy. A minimal 30-day stay at the sanatorium also includes high quality nutrition with a solid content of antioxidants (5-7).

As a part of long-term observation, randomly selected groups of children with respiratory problems were treated with orally administered β-glucan in the hope of positively influencing inflammation and improving clinical manifestation of the disease.

β-glucans belong to a group of biologically active natural compounds. Glucans represent highly conserved structural components of cell walls in fungi, yeast, and seaweed. Generally, β-glucan is a chemical name of a polymer of β-glucose and exists as a homopolymer of glucose having a linear molecule with (1-3)-β-D-glycosilic linkages or a branched one with side chains bound by (1-6)-β-D-glycosilic linkages.

Extensive research in the last decade introduced four new types of glucan with improved purities and effectiveness that significantly stimulate several types of immune reactions oriented against microbes, toxic factors, cancer and other influences (8-10). Additional studies showed strong effects on hypertension, cholesterol levels, and arthritis (11).

During the past 30 years, several forms of mushroom-derived β-glucan have been approved in Japan for treatment of cancer patients (12). In most other countries, glucan is still only a natural supplement. However, extensive research is now devoted on the use of glucan in clinical practice, including numerous clinical trials (5-7,13).

Four parameters, (I) salinary levels of lysozyme; (II) C-reactive protein (CRP); (III) albumin and (IV) calprotectin, were used for the evaluation of acute inflammatory response and the quality of nonspecific immunity in children. The reason for using these parameters is the fact that salivary sampling is nonagressive, fast and a well standardized technique that does not require the presence of highly qualified personnel. At the same time, saliva offers testing on a wide range of immunological parameters (2-4,14-18).

Salivary lysozyme is produced by salivary glands (the highest production can be found in submandibular glands) and by neutrophil granulocytes (19). Its enzymatic effects are oriented mostly against G-positive microorganisms via damaging their peptidoglycans. Some studies suggest antiviral effects. In many cases, bactericidal effects of lysozyme are independent of its enzymatic activity (15,19). Lysozyme levels are most likely influenced by the level of stress (16). High levels suggest bacterial, viral and/or yeast infection (19).

CRP is an acute inflammation protein, registering inflammatory response (20,21). Higher levels can be found in saliva of children suffering from gingivitis and periodontitis (22). CRP gets into the saliva both by active transport and by difusion, but is also produced locally by salivary glands (16,17). Its major role in nonspecific immunity is its ability to bind phosphocholin, to bind phospholipids from damaged cells and to recognize pathogen with resulting activation of the classical complement pathway with C1q component serving as an opsonin (20).

Salivary albumin is an indicator of appearance of plasmatic proteins in the oral cavity (22). Changes in its levels signal local immune response to the environmental stress (2). Even when albumin represents negative protein of an inflammatory reaction, in saliva, its levels actually increase during inflammation (16).

Pleiotropic function of calprotectin is mostly connected with antiinflammatory reactions including both antimicrobial mechanisms and Th1-mediated response (23). Calprotectin was originally described as antimicrobial protein present in plasma of neutrophils (23-25). Later studies suggested that calprotectin is a promising indicator of inflammation or an indicator of various immune processes taking place in an organism (26,27). Calprotectin is also important as a barrier forming antimicrobial shield (25). Decrease in calprotectin levels leads to reduction of natural immune reactions and to higher sensitivity to infections (25,27,28). It serves as a strong antiinflammatory chemoattractant of neutrophils and monocytes, but at the same time can directly destroy microorganisms (25). Some studies suggested induction of apoptosis, which can be stopped by the addition of zinc. Inhibition of microbial growth in the organisms results from competition between calprotectin and bacteria for zinc (27). Sensitivity and dynamics of calprotectin levels occurrs before changes in CRP levels (27,28) and in saliva, the levels of calprotectin do not correlate with the levels of CRP (28). However, calprotectin is comparable to CRP in its ability to recognize viral and bacterial infections and has positive effects on affected organs (27,28).

As we tried to gain better information about immune mechanisms taking place in a selected population of children treated with climatotherapy and supplemented with β-glucan, we evaluated a broad spectrum of parameters of nonspecific immunity.

Materials and methods

Protocol

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial compared β-glucan #300 and placebo in children. From sixty children we used 56, as 4 did not spend a full 30 days in the sanatorium. These children were randomly divided into placebo (C) group (12 females, 15 males, age 5-15, average 10.0±2.67) and glucan supplemented (GL) group (13 females, 16 males, age 7-11, average 9.7±2.04). Subjects were randomly assigned to groups which were blinded to intervention. During the intervention period, subject consumed 100 mg/d of β-glucan or placebo. Both glucan and placebo capsules looked identical. The whole study was performed at the Sanatorium for Respiratory Diseases EDEL (Zlate Hory, Czech Republic), where the children were enrolled in a 30-day trial. The study was approved by the Ethics committee of the Public Health Institute and Sanatorium Edel Czech Republic. This study was performed in agreement with Helsinki declaration (revised version 2000.09.01) and in full agreement of rules for clinical testing for the Czech Republic. Parental consent was given in all cases. Throughout the entire stay, the children were under regular supervision by medical staff.

Glucan

Yeast-derived insoluble glucan #300 were purchased from Transfer Point (Columbia, SC). This glucan is over 85% pure.

Saliva collecting

In all subjects we obtained saliva at the beginning of the study and at the conclusion of their stay in Sanatorium. We used identical times (between 8 and 9 AM) for sampling, so the possible influence of circadian rhythms could be eliminated. Saliva was collected using a commercial Salivette device (Sarstead, Orsay, France). A cotton swab was added into a sterile container and centrifuged at 1,000 g for 5 minutes and stored at –20 °C (2,5,16).

Quantification of salivary proteins

We measured the levels of albumin, and CRP using nephelometer Siemens BN II as suggested by the manufacturer. Lysozyme was measured using photometer Dynex MRX (The Microtiter Comp.) using egg lysozyme as a standard. Calprotectin was measured using material and system Buehelman Switzerland Quantum Blue.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was evaluated by a Wilcoxon pair t-test using a GraphPad Prism 5.04 software (GraphPad Software, USA). Statistical significance between individual groups used a P<0.05 level.

Results

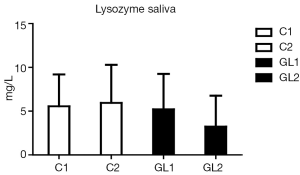

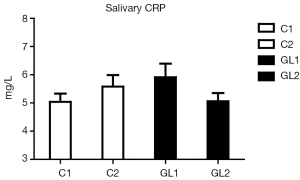

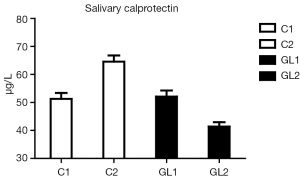

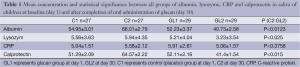

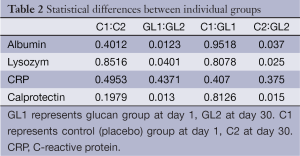

In all starting values (day 1), no significant differences between control (C) and GL groups were found. Placebo group also showed no differences between day 1 and day 30. On the other hand, in the GL group, significant changes in levels of albumin, lysozyme and calprotectin were found. In the case of CRP, the changes were not statistically significant.

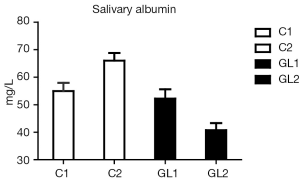

Figure 1 summarizes our findings of the level of albumin. Significantly lower levels of albumin strongly suggest reduction of inflammatory irritation in glucan-treated children. Similar data were found in case of lysozyme (Figure 2). Figure 3 suggests a decrease of the CRP levels in glucan supplemented children, but these changes are not statistically significant.

The strongest effects were found in case of calprotectin (Figure 4). On one hand, the level of calprotectin significantly decreased in the glucan group. On the other hand, we found an unsignificant, but still visible increase of calprotectin. The intensity of changes is particularly pronounced when we compare the levels at the end of the study, where the results were significant at the P<0.015 level. All these findings were accompanied by pronounced improvements in the general physical health of tested individuals. Tables 1 and 2 summarize the obtatained values and all statistical parameters.

Full table

Full table

Discussion

Salivary defense factors, including factors such as CRP and lysozyme, represent a significant part of mucosal immunity—particularly in immunodeficient patients (29) and children prone to respiratory infections (30). In this study we increased the experimental group described previously (6-8). Data obtained from this enlarged group confirmed our original data and again showed significant effect of β-glucan treatment. CRP levels, higher levels of which document more accute inflammation than persisting long-term inflammatory pressure (16,20). Strong effects of β-glucan on lysozyme levels demonstrate significant effects on bacterial infections and reduction of chronic inflammation. This is shown by average levels of albumin. The decrease of these levels again reflects reduction of inflammation and lower transduction of this protein from capillaries to the saliva.

Compared to our previous findings, we found an increase in albumin levels in control group, which reflects the fact that this particular group of children came to the Sanatorium with higher inflammatory load, most probably caused by worse climatic and environmental conditions from children’s homes, where the pollution is significantly worse during spring and fall (6-8,18). These findings are further supported by the dynamics of the changes in calprotectin levels, where in control group we again found small increase, but the β-glucan treatment caused strong decrease in the level of calprotectin, which can be considered to be the most important finding of our study. We found that correlation of albumin and calprotectin levels is almost linear. No such correlation has been found in other tested proteins.

The dynamics of these changes show significant antimicrobial effects of glucans (31) which offers strong protection by acting as an endogenous ligand of the TLR4 receptor and increases all facets of an antiinfectious response (23).

Repeated study using new groups of children offered a possibility to verify the optimal dose of β-glucan, as several factors such as age, sex and weight influence its required dose, particularly in case of physical load (32). We believe that an increase in spectrum of natural immunity parameters offered better evaluation of effects of β-glucan in children with respiratory problems. We have confirmed the previous data showing that of β-glucan treatment has positive stimulatory effect on mucosal immunity. Based on our results we can conclude that glucan administration might be considered to be a highly promising and at the same time inexpensive method in the treatment of chronic respiratory problems in children.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Technology Agency of the Czech Republic TACR TA 0202094.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cobanoglu N, Galip N, Dalkan C, et al. Leptin, ghrelin and calprotectin: inflammatory markers in childhood asthma? Multidiscip Respir Med 2013;8:62. [PubMed]

- Francis JL, Gleeson M, Lugg DJ, et al. Trends in mucosal immunity in Antarctica during six Australian winter expeditions. Immunol Cell Biol 2002;80:382-90. [PubMed]

- Soo-Quee Koh D, Choon-Huat Koh G. The use of salivary biomarkers in occupational and environmental medicine. Occup Environ Med 2007;64:202-10. [PubMed]

- Lee SY, Chang YS, Cho SH, et al. Allergic diseases and air pollution. Asia Pac Allergy 2013;3:145-54. [PubMed]

- Vetvička V, Richter J, Svozil V, et al. Placebo-driven clinical trials of Transfer Point Glucan #300 in children with chronic respiratory problems: III. Clinical findings. Am J Immunol 2013;9:88-93.

- Vetvička V, Richter J, Svozil V, et al. Placebo-driven clinical trials of Transfer Point Glucan #300 in children with chronic respiratory problems: antibody production. Am J Immunol 2013;9:43-7.

- Vetvicka V, Richter J, Svozil V, et al. Placebo-driven clinical trials of yeast-derived β-(1,3) glucan in children with chronic respiratory problems. Ann Transl Med 2013;1:26.

- Vetvicka V, Vetvickova J. A comparison of injected and orally administered β-glucans. JANA 2008;11:42-8.

- Vetvicka V, Vetvickova J. Effects of glucan on immunosuppressive actions of mercury. J Med Food 2009;12:1098-104. [PubMed]

- Vetvicka V, Novak M. Biological action of b-glucan. In: Vetvicka V, Novak M. eds. Biology and Chemistry of Beta Glucan. Bentham Science Publishers, 2011:10-8.

- Vetvicka V, Vetvickova J. Physiological effects of different types of beta-glucan. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 2007;151:225-31. [PubMed]

- Hamano K, Gohra H, Katoh T, et al. The preoperative administration of lentinan ameliorated the impairment of natural killer activity after cardiopulmonary bypass. Int J Immunopharmacol 1999;21:531-40. [PubMed]

- Bergendiova K, Tibenska E, Majtan J. Pleuran (β-glucan from Pleurotus ostreatus) supplementation, cellular immune response and respiratory tract infections in athletes. Eur J Appl Physiol 2011;111:2033-40. [PubMed]

- Bonne NJ, Wong DT. Salivary biomarker development using genomic, proteomic and metabolomic approaches. Genome Med 2012;4:82. [PubMed]

- Fábián TK, Hermann P, Beck A, et al. Salivary defense proteins: their network and role in innate and acquired oral immunity. Int J Mol Sci 2012;13:4295-320. [PubMed]

- Krasteva A, Kisselova A. Salivary acute phase proteins as biomarker in oral and systemic disease: acute phase proteins as early non-specific biomarkers of human and veterinary diseases. In: Veas F. eds. Tech, Rijeka, Croatia, 2011:69-88.

- Pfaffe T, Cooper-White J, Beyerlein P, et al. Diagnostic potential of saliva: current state and future applications. Clin Chem 2011;57:675-87. [PubMed]

- Zhang L, Xiao H, Wong DT. Salivary biomarkers for clinical applications. Mol Diagn Ther 2009;13:245-59. [PubMed]

- Bard E, Laibe S, Bettinger D, et al. New sensitive method for the measurement of lysozyme and lactoferrin for the assessment of innate mucosal immunity. part I: time-resolved immunofluorometric assay in serum and mucosal secretions. Clin Chem Lab Med 2003;41:127-33. [PubMed]

- Gruys E, Toussaint MJ, Niewold TA, et al. Acute phase reaction and acute phase proteins. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B 2005;6:1045-56. [PubMed]

- Mohamed R, Campbell JL, Cooper-White J, et al. The impact of saliva collection and processing methods on CRP, IgE, and Myoglobin immunoassays. Clin Transl Med 2012;1:19. [PubMed]

- Ramamoorthy RD, Nallasamy V, Reddy R, et al. A review of C-reactive protein: a diagnostic indicator in periodontal medicine. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 2012;4:S422-6. [PubMed]

- Bosco Dhas DB, Bhat BV, Gane DB. Role of calprotectin in infection and inflammation. Curr Pediatr Res 2012;16:83-94.

- Cuida M, Brun JG, Tynning T, et al. Calprotectin levels in oral fluids: the importance of collection site. Eur J Oral Sci 1995;103:8-10. [PubMed]

- Tieu DD, Peters AT, Carter RG, et al. Evidence for diminished levels of epithelial psoriasin and calprotectin in chronic rhinosinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;125:667-75. [PubMed]

- Hsu K, Champaiboon C, Guenther BD, et al. Anti-infective protective properties of S100 calgranulins. Antiinflamm Antiallergy Agents Med Chem 2009;8:290-305. [PubMed]

- Stríz I, Trebichavský I. Calprotectin - a pleiotropic molecule in acute and chronic inflammation. Physiol Res 2004;53:245-53. [PubMed]

- Johne B, Fagerhol MK, Lyberg T, et al. Functional and clinical aspects of the myelomonocyte protein calprotectin. Mol Pathol 1997;50:113-23. [PubMed]

- Kirstilä V, Tenovuo J, Ruuskanen O, et al. Salivary defense factors and oral health in patients with common variable immunodeficiency. J Clin Immunol 1994;14:229-36. [PubMed]

- Lehtonen OP, Tenovuo J, Aaltonen AS, et al. Immunoglobulins and innate factors of immunity in saliva of children prone to respiratory infections. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand C 1987;95:35-40. [PubMed]

- Dale BA, Fredericks LP. Antimicrobial peptides in the oral environment: expression and function in health and disease. Curr Issues Mol Biol 2005;7:119-33. [PubMed]

- Nieman DC, Henson DA, McMahon M, et al. Beta-glucan, immune function, and upper respiratory tract infections in athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2008;40:1463-71. [PubMed]