The Cleveland Clinic: a distinctive model of American medicine

Founded in 1921, the Cleveland Clinic (hereafter called “the Clinic”) represents a distinctive model of American medicine. The Clinic was conceived as and remains a closed staff, not-for-profit, multidisciplinary group practice. Its physicians are salaried, have one-year contracts which are renewed annually through a rigorous visioning and evaluative process called the Annual Professional Review (or “APR”), and the Clinic is physician-led. These elements of its distinctive model and culture are the subject of this brief review. More comprehensive descriptions of the organization are also available (1,2).

In 1921, four Cleveland physicians—three surgeons and an internist—returned from their World War I duty in a military hospital in France and conceived the model for the Clinic, which was radical for its time. Drs. William Lower, Frank Bunts, George Crile Sr., and John Phillips imagined and implemented a group practice on their return from France that was the Cleveland Clinic and which was founded on the principle they had enacted in their military experience of “To Act as A Unit” (1). The mutual dependency and culture of collegiality that are framed by “acting as a unit” define and perhaps differentiate the Clinic today. The four founders were medical innovators and envisioned a tripartite mission of superb clinical care, medical research, and education which they framed as “better care of the sick, investigation of their problems, and more teaching of those who serve.” Each of these components of the mission of the Clinic is thriving today, as the institution ranks highly in all three arenas of academic medicine. For example, the Clinic has consistently been ranked among the top four ranked American hospitals in U.S. News and Work Report [including ranking first in Cardiovascular Care for 19 consecutive years and in the top 10 in 13 other specialties (3)], features ~$250 million in extramural research funding with among the highest ranked per capita funding for its scientists, and serves a large number of medical educational audiences, including medical students, graduate medical trainees, practicing health care providers, and patients (4). Entry to the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine and to the Clinic’s 70 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)—approved training programs is highly competitive, with 1,932 applicants for 32 positions in the medical school and ~12,000 applications for approximately 300 training positions, respectively.

In the context that “culture eats strategy for lunch” (5), it is the culture of the Clinic that has its roots in the founders’ vision and its model of medicine that is, in my view, the differentiating feature of the institution. The group practice of medicine is elegantly realized at the Clinic; colleagues collaborate and are vigorously and authentically available to each other in the mutual care of their patients. The fact that physicians are salaried—without bonuses or volume incentives for care—allows physicians to make clinical judgments that are devoid of personal financial considerations. The fact that all physicians on the faculty (called “Staff physicians”) have one-year contracts with annual reassessment and reappointment creates a culture of performance, accountability, and the ability to realize professional goals over time. In fact, this process of annual review—called the Annual Professional Review (6)—is at the core of the Clinic’s culture and performance and so merits a brief discussion. Every physician at the Clinic—including the Chief Executive Officer and the Chief of Staff—undergo an APR annually. Annual Professional Reviews are scheduled by the institute in which the physician practices and occur in each quarter of the year. The usual process begins with the physician’s logging on to an on-line repository for APR reports (called the Staff Information System) and completing a templated annual report which captures a summary of the physician’s activities over the year and goals for the year ahead in all relevant professional dimensions—clinical, research, administrative, and education. The next steps in the APR are two 30-minute face-to-face conversations, the first with the Institute and Department Chairpersons (called APR 1) and the second (called APR 2) with a member of the Medical Executive Committee (MEC, an elected member of the physician Staff). The APR 1 conversation is a forum in which the individual member of the Staff and the Institute/Department Chairpersons charter with each other regarding goals and aspirations for the year ahead. The Chairpersons will review and share the year’s metrics—clinical, research, and educational—with the individual Staff physician and articulate their hopes for the year ahead. The individual Staff member will present a personal vision for the year ahead, perhaps hopes to expand one sphere of professional activities, to change the mix of activities (e.g., more research by applying for federal funding), or to maintain the current year’s activities. At its best, the APR 1 conversation ends with clarity about performance and upcoming goals by both parties and the Chairpersons will document the discussion on line in the Staff information System. Once APR 1 is complete, the APR 2 conversation follows. Here, the member of the Medical Executive Committee’s goal is to assess the individual Staff physician’s perspective, i.e., whether his/her vision for her career has been realized, impressions about the direction of his/her Department and Institute, and impressions about the performance of the Chairpersons. Assigned to a specific institute to preserve longitudinal continuity, the MEC member will be speaking with a number of members of the Staff and so will be able to elicit common themes among the physicians in that institute. These themes are synthesized and then articulated at a quarterly meeting of the MEC devoted to review the institutes whose APRs occur in that quarter. At these quarterly meetings, the institute Chairperson will undergo his/her APR, which is a 30-minute comprehensive summary of the institute’s performance over the year that is presented to the Clinic’s leadership, including accomplishments in clinical care, research, and education; financial performance; misses; goals; exemplary Staff performers; and an overall synthesis. This presentation is followed by questions to the Chairperson from the CEO, Chief of Staff, and members of the MEC. During this discussion, comments regarding themes from the institute physician Staff are invited from the MEC APR 2 reviewers. Through the sharing of these themes, the Chairpersons are apprised of feedback from the Staff in their institute. The institute Chairperson is then dismissed from the meeting, after which the MEC discusses her/his performance. The process is completed when the institute Chairperson receives the Medical Executive Committee’s feedback summary in a meeting with the Chief of Staff and the MEC APR 2 reviewer(s). The staff in the institute then will receive re-appointment letters and notification of any change in compensation for the year ahead.

Given the importance and time-honored value of the APR to the Clinic, substantial time is devoted to the APR process yearly; this time was estimated to be approximately 7,100 person-hours when the Staff numbered 1,700 (6). Today, as the Staff has grown to ~3,200, approximately 13,000 person-hours or six senior full-time equivalents are dedicated to the APR. The centrality of the APR to the culture and function of the Clinic relates to its driving conversations and concordance between the Staff member and leadership regarding professional goals for the individual, institute, and department, while assuring accountability for performance based on the prior year’s goals and commitments. In driving recurring, frank discussions between colleagues, the APR has been considered the fabric or “glue” of the Clinic’s group practice. A 2006 survey by Stoller et al. of methods of professional review among top U.S. News and World Report hospital Chief Executive Officers indicated that the APR process differentiates the Clinic substantially both in the thoroughness of the process and the time expended (6).

Clinical care at Cleveland Clinic is its core mission as indicated by an institutional commitment to “Patients First.” The quality of care is demonstrated in many ways beyond the U.S. News and World Report rankings, including the Clinic’s being a destination for medical tourism by visitors from many countries, including China, who seek the expertise of the Staff and the quality of their work (4). Transparency in the clinical work of the Clinic is paramount, e.g., as demonstrated by the yearly publication of outcomes books by each institute which contain non-risk-adjusted outcomes. Examples of included outcomes include survival post cardiac surgery, success in weaning long-term ventilator-dependent patients from mechanical ventilation, rate of central line blood stream infections in the intensive care units, etc.

Regarding research, the Clinic has had a longstanding tradition of medical innovation and discovery, both in basic science and in translational and clinical research. Noteworthy examples include performance of the world’s first coronary angiography and first coronary revascularization surgery, pioneering work in hypertension, breast surgery, laryngeal and face transplantation, the genetics of cardiovascular disease, neuroscience, and biomedical engineering (1). Cleveland Clinic scientists and investigators are actively engaged in both investigator-initiated research as well as participation in many National Institutes of Health multicenter collaborative trials. In the case of just one of the institutes, the Respiratory Institute, trials in which Respiratory Staff have participated include the Registry for Individuals with Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency (7), the Lymphangioleiomyomatosis Registry, the Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network [ARDSNet (8)], the National Emphysema Treatment Trial [NETT (9)], and the Long-term Oxygen Treatment Trial (LOTT). Taken together, the research activities at the Clinic overall attract ~$250 million in extramural funding yearly (4).

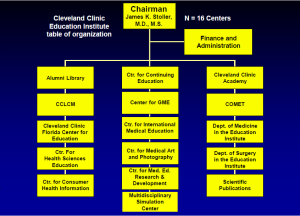

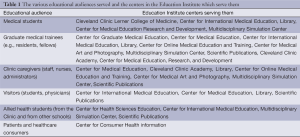

The third element of the Clinic’s mission—“more education of those who serve”—is addressed by the Education Institute (10). Education has grown organically at the Clinic since its inception in 1921, when the first residents received their training and the Department of Medical Art and Photography was formed. Over the ensuing 92 years, the educational mission of the Clinic and the Education Institute have both grown substantially such that currently, many different educational audiences are served by the Education Institute’s 16 centers (Figure 1) (Table 1).

Full table

Among the 16 centers in the Education Institute, four may be of special interest to international audiences: the Center for Graduate Medical Education, the Center for International Medical Education, the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine (Scientific Publications), and the Cleveland Clinic Academy.

The Center for Graduate Medical Education oversees the training programs at the Clinic in >70 specialties which train >1,200 trainees. Graduate medical education at the Clinic has had an international footprint in that >12,000 physicians have graduated from Clinic’s training programs over 92 years and are practicing in all states of the United States and in 71 other countries, including China.

The Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine has been in continuous publication since 1931 and is currently ranked as the second most read medical journal among office-based cardiologists and internists in the United States. Its website—www.ccjm.org—received 3.95 million visits in 2013, 45% of which were by visitors outside the United States.

The Center for International Medical Education oversees the Clinic’s observer and preceptor programs and helps arrange conferences in collaboration with international groups. In 2013, 751 observers visited the Clinic (of >2,500 applicants) and the preceptor program, which provides dedicated resources for visitors sponsored by a single group or organization, welcomed visitors from several countries, including China. Thirty six international conferences in a variety of disciplines were organized in 2013.

Finally, the Cleveland Clinic Academy in the Education Institute is the center that organizes and offers curriculum in leadership development. Based on the premise that effective leadership is much needed in health care but that physicians do not receive training in the specific leadership competencies that are associated with effective leadership, the Cleveland Clinic Academy was organized to offer an extensive curriculum in leadership competencies to Clinic caregivers and, in its executive education programs, to international visitors. Internally, more than 50 courses are offered annually which have been attended by 7,510 Clinic caregivers. Two executive education programs have particularly attracted the attention of international visitors: the Executive Visitors Program and the Samson Global Leadership Academy for Healthcare Executives (11). The Executive Visitors Program is a 3-day immersion experience that describes how the Cleveland Clinic operates. To date, the 288 visitors (from the 23 states in the United States and 21 additional countries) have attended the program, which offers a series of lectures by Cleveland Clinic leaders regarding key functions of the Clinic—quality, finance, research, nursing, education, compensation, etc.—along with opportunities to network with Clinic leaders to begin ongoing dialogs. The second executive education program—Samson Global Leadership Academy—offers a two-week residential program for healthcare executives, including physicians, nurses, and administrators, who seek a deep dive into their own leadership development. The program offers a curriculum of participatory lectures on leadership competencies that are taught by faculty dyads—characteristically a business school expert who partners with a content expert member of the Clinic faculty. The didactic curriculum of the Samson Global Leadership Academy is coupled with experiential learning that is centered around the competencies needed to lead a best-in-class healthcare organization (e.g., communication, negotiation, conflict resolution, emotional intelligence, fiancé and accounting, situational leadership, etc.). Offered twice a year in April and October, the Samson Global Leadership Academy has welcomed 70 executives from 18 countries to date and is developing an international community of healthcare leaders who remain connected with the Clinic and with each other through a Clinic closed social network (www.SamsonExecEdConnect.com) that allows ongoing networking, learning, and connection among colleagues.

In summary, Cleveland Clinic features a distinctive model and culture that helps drive its best-in-class performance in all three arenas of academic medicine: clinical care, research, and education. In this regard, the Clinic has remained true to the mission framed by its four founders: “better care of the sick, investigation of their problems, and more teaching of those who serve”.

Acknowledgements

Disclosure: The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Clough J. eds. To Act as a Unit: The Story of the Cleveland Clinic, 5 edition. Cleveland Clinic Press, 2012.

- Kastor JA. Point-counterpoint: The Cleveland Clinic institute system is the right structure for academic health centers in the 21st century. Acad Med 2012;87:558. [PubMed]

- U.S. News and World Report hospital rankings, 2013. Available online: health.usnews.com. Accessed December 1, 2013.

- Cleveland Clinic Annual Report. Available online: http://my.clevelandclinic.org/about-cleveland-clinic/overview/financial-information.aspx. Accessed December 1, 2013.

- Parr S. “Culture eats strategy for lunch”. Fast Company. Available online: www.fastcompany.com. January 24, 2012. Accessed December 1, 2013.

- Stoller JK, Coulton R, Kay R. Survey of methods of professional review for physicians in highly rated medical centers. J Med Pract Manage 2006;22:152-8. [PubMed]

- McElvaney NG, Stoller JK, Buist AS, et al. Baseline characteristics of enrollees in the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Registry of alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency. Alpha 1-Antitrypsin Deficiency Registry Study Group. Chest 1997;111:394-403. [PubMed]

- Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. Available online: www.ARDSNet.org. Accessed December 1, 2013.

- Fishman A, Martinez F, Naunheim K, et al. A randomized trial comparing lung-volume-reduction surgery with medical therapy for severe emphysema. N Engl J Med 2003;348:2059-73. [PubMed]

- Stoller JK. The Education Institute. In: To Act as a Unit: The Story of the Cleveland Clinic, 5 edition. Cleveland Clinic Press, 2012.

- Cleveland Clinic Executive Education. Available online: www.clevelandclinic.org/ExecEd. Accessed December 1, 2013.