Identifying optimal candidates of transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) vs. sorafenib in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma

Introduction

Liver cancer is the seventh most common primary malignant tumor and the third most significant cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide (1), with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) accounting for more than 90% of cases (2). Due to its invasive and latent characteristics, the majority of HCC patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage beyond the indications of curative treatments like hepatectomy, liver transplantation, and local ablation therapy (3). On the basis of the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system, patients classified as BCLC stage C with symptomatic tumors [performance status (PS), 1–2], vascular invasion, or extrahepatic spread have a dismal prognosis with expected median overall survival (OS) of 6–8 months (4). Sorafenib, an orally administered multikinase inhibitor, has been recommended as the first-line treatment and shown to prolong the median OS of patients with advanced unresectable HCC (5,6).

Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) is the standard therapy for intermediate-stage HCC patients (PS 0 and multinodular asymptomatic tumors without vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread) according to the BCLC staging classification (4). It has been verified to improve survival outcomes especially when combined with other therapies including radiofrequency ablation and stereotactic body radiation therapy in several studies (7,8). Notably, increasing evidence supports the application of TACE in patients with early- and advanced-stage HCC (9,10).

The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG-PS) is commonly used for stratifying HCC stage and selecting appropriate patients in treatment decisions in the BCLC system (11). Additionally, ECOG has been demonstrated to be one of the independently powerful prognostic factors of HCC patients in each stage undergoing different treatment modalities (12-14).

Although the availability of TACE therapy in advanced HCC has been preliminarily revealed in published studies, whether BCLC stage C patients with PS 1 with no vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread can benefit from TACE therapy as compared to sorafenib therapy remains controversial.

This present study aimed to compare the outcomes of TACE and sorafenib and identify the prognostic factors related to OS for BCLC stage C patients with PS 1 but without vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread.

Methods

Study design and participants

This retrospective study included consecutive HCC patients who underwent TACE or sorafenib therapy at our department from January 2010 to December 2017. The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (I) patients classified as BCLC stage C; (II) no vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread; (III) ECOG-PS score 1; (IV) no previous therapy for HCC. Patients were excluded if any of the following conditions were present: (I) patients with other uncontrolled ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, or simultaneous malignancies of other system; (II) patients with cardiopulmonary, renal, or cerebral dysfunction.

HCC was diagnosed by contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) on the basis of the American Association for the Study of the Liver Disease or European Association for the Study of Liver disease (AASLD/EASL) guidelines (15,16). Clinical, laboratory, and imaging data of enrolled patients were collected from hospital database. Given the retrospective study design, the requirement to obtain informed consent was waived. This investigation was approved by the ethics committee of the hospital and performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki on human research.

Treatment and follow-up

In the sorafenib procedure, sorafenib was initially taken as a standard dose of 400 mg twice daily (800 mg/d). Dose modification or treatment interruption temporarily was performed if drug-related toxicity was according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria Adverse Events version 3.0. Sorafenib was constantly administered as long as possible until unacceptable toxicities occurred, disease progression developed, or the patient died. All patients were followed up every 2 weeks in the first 6 weeks and every 6–8 weeks in subsequent therapeutic process, as appropriate.

For the TACE procedure, the Seldinger technique was used and a 4.1-French RC1 catheter was introduced into the tumor feeding artery. Afterwards, the number, location, size, and branches of the feeding vessels of the tumor were carefully identified. A mixture of 10–20 mL iodized oil, gelfoam particles with 30–50 mg doxorubicin and 50–100 mg cisplatinum were injected into the arterial branches. TACE therapy was carried out every 6 weeks in the first year and every 6–8 weeks thereafter, depending on the patient’s liver function and tumor necrosis.

Routine examinations were conducted at each follow-up, including physical examinations, blood tests serum AFP level, serum biochemistry, liver biochemistry], and imaging examinations (chest X-ray, abdominal ultrasonography, abdominal CT or MRI).

Statistical analysis

OS was defined as the time from the date of TACE or sorafenib until death or the last follow-up. The last visit was completed on January 10, 2019. Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies. Continuous variables are expressed as medians and inter-quartile ranges. Differences of baseline characteristics of enrolled patients between the 2 groups were compared using χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. Survival analyses were performed using the Kaplan-Meier analysis, and the statistical differences between the TACE and sorafenib groups were examined by the log-rank test. The Cox proportional hazards regression model was used for calculating the hazard ratio for survival and its 95% confidence intervals (CI) of prognostic factors for OS according to the univariate and multivariate analyses. Statistical significance was taken as a two-side P values <0.05 for all analyses. Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS software version 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics

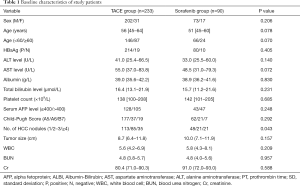

According to the inclusion criteria, a total of 323 consecutive patients with BCLC stage C HCC were enrolled in this present study. Of these patients, the TACE group and sorafenib group comprised 233 and 90 patients, respectively. The characteristics between the two groups were not significantly different according to the statistical analysis. The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Full table

Survival analyses of patients between in the ACE and sorafenib groups

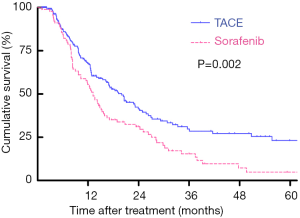

The last follow-up for all included patients was December 2019. For the patients undergoing TACE therapy, 106 patients died during a median follow-up period of 20.9 months. Meanwhile, in the sorafenib group, only 14 patients were alive while the median follow-up reached 39.7 months. Based on the Kaplan-Meier curves, patients treated with TACE showed a better OS than those undergoing sorafenib, with respective OS at 1, 3, and 5 years (67.7%, 41.5%, 23.2% vs. 55.6%, 29.6%, 4.8%; log-rank P=0.002; Figure 1).

Univariate and multivariate analyses of OS

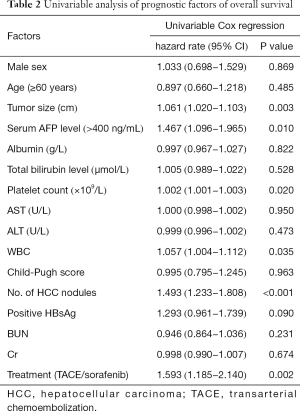

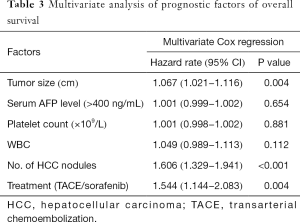

Based on the univariate analysis for OS, the following factors were associated with survival: tumor size, tumor number, and treatment method, along with platelet (PLT), white blood cell (WBC), and AFP count (P<0.05; Table 2). The factors above were calculated in multivariate analysis. The results of multivariate analysis revealed that tumor size (HR 1.067, P=0.004), tumor number (HR 1.606, P<0.001), and treatment method (HR 1.544, P=0.004) were identified as independent predictors of OS (Table 3).

Full table

Full table

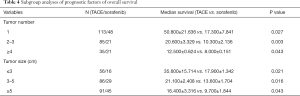

Subgroup analysis

Tumor size and tumor number were further stratified into different groups to identify whether the two factors influenced the efficacy of HR. Tumor size was divided into three groups. For patients with a tumor size hence, those undergoing TACE showed a better OS than those treated with sorafenib (log-rank P=0.021). For patients with a tumor size between 3–5 cm, there was a significant difference in OS between the two groups (log-rank P=0.016). Among the patients with a tumor size 016). Athose undergoing TACE showed a better OS than those treated with sorafenib (log-rank P=0.043). Furthermore, tumor number was classified into three groups (1 tumor, 2–3 tumors, ≥4 tumors). In entire subsets according to the subgroup analyses, patients in the TACE group showed a better OS than those in the sorafenib group. The results of the subgroup analysis are summarized in Table 4.

Full table

Discussion

In this present retrospective study, we demonstrated that TACE showed a significantly better OS in BCLC stage C patients with PS 1 but without vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread, compared with patients undergoing sorafenib therapy. Furthermore, TACE therapy (vs. sorafenib) was an independent predictive factor of better OS, while tumor size and tumor number were independent predictors of poorer OS.

Based on the BCLC staging system, sorafenib is proposed as the standard treatment option for HCC patients in BCLC stage C which includes a great diversity of patients with single or multiple factors, such as symptomatic tumors causing an adverse effect on PS (ECOG PS 1–2), macrovascular invasion (either segmental or portal invasion), or extrahepatic spread (lymph node involvement or metastases). As for the considerable heterogeneity, a diversity in prognosis was observed in the C stage under the treatment of sorafenib with unsatisfactory efficacy (17). Multiple previous studies have advocated for TACE in patients with vascular invasion, showing a better survival outcome compared with sorafenib (18). Additionally, PS, which is applied to assess patient’s capability of self-care, is deemed to be a powerful predictive factor with respect to OS for HCC patients. As is well known, treatment modality is highly related to the OS of HCC patients. PS, to some extent, could influence treatment decisions. In order to avoid confounding factors, only patients with PS 1 but without vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread undergoing TACE or sorafenib were enrolled in this present study. The findings indicated that TACE was more effective than sorafenib in enhancing prognostic survival in these patients. This result gives credence to TACE as a potentially more effective treatment option for BCLC stage C patients with PS 1 but without vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread.

Univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted to revealed prognostic factors in relation to OS. Patients with poor prognosis were associated with a high grade of ECOG-PS which has been proven in previous studies. Additionally, in this study, different treatment methods became a significant independent predictor of OS other than tumor size and number. Nevertheless, the Child-Pugh score, albumin (ALB) and total bilirubin (TBLI) exhibited no statistical significance which might have been due to the small sample size. Additionally, the subgroup analysis revealed that both TACE and sorafenib were significantly related to OS in the entire subsets in which TACE provided a better prognostic performance than sorafenib.

Despite these findings, there are still several limitations for this study that should be addressed. The primary limitation is that the retrospective design of this study might have introduced information bias, even though all the procedures and administrations were conducted by the same seasoned team in order to ensure the quality control and alleviate potential bias. Additionally, this study was carried out at a single center with a relatively small sample size which might have reduced its representativeness. Further high-quality prospective studies with a large sample size are needed. Finally, most of the patients in our study were Chinese with an infection of hepatitis B virus as the cause of HCC, compared with most western countries where the etiologies of HCC are mainly hepatitis C virus infection and alcoholic liver disease.

In conclusion, this retrospective study demonstrated that TACE therapy could provide a better survival outcome and should be suggested as an alternative treatment modality to sorafenib for BCLC stage C patients with PS 1 but without vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm.2020.02.123). LL serves as the unpaid editorial board member of Annals of Translational Medicine from Apr 2020 to Mar 2022. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Given the retrospective study design, the requirement to obtain informed consent was waived. This investigation was approved by the ethics committee of the hospital and performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki on human research.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:394-424. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Galle PR, Forner A, Llovet JM, et al. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2018;69:182-236. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhong JH, Peng NF, You XM, et al. Tumor stage and primary treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma at a large tertiary hospital in China: A real-world study. Oncotarget 2017;8:18296-302. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heimbach JK, Kulik LM, Finn RS, et al. AASLD guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2018;67:358-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advancedhepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:25-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2008;359:378-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim W, Cho SK, Shin SW, et al. Combination therapy of transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and radiofrequency ablation(RFA) for small hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison with TACE or RFA monotherapy. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2019;44:2283-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jun BG, Kim SG, Kim YD, et al. Combined therapy of transarterial chemoembolization and stereotactic body radiation therapy versus transarterial chemoembolization for ≤5cm hepatocellular carcinoma: Propensity score matching analysis. PLoS One 2018;13:e0206381. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xiang X, Lau WY, Wu ZY, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization versus best supportive care for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus: a multicenter study. Eur J Surg Oncol 2019;45:1460-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Le Y, Shen JX, Zhang YF, et al. Transarterial Chemoembolization related to Good Survival for Selected Patients with advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Cancer 2019;10:665-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hsu CY, Lee YH, Hsia CY, et al. Performance status in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: determinants, prognosticimpact, and ability to improve the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer system. Hepatology 2013;57:112-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu J, Li A, Yang J, et al. Efficacy and safety of TACE in combination with sorafenib for the treatment of TACE-refractory advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in Chinese patients: a retrospective study. Onco Targets Ther 2017;10:2761-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vitale A, Burra P, Frigo AC, et al. Survival benefit of liver resection for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma across different Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stages: a multicentre study. J Hepatol 2015;62:617-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Facciorusso A, Del Prete V, Antonino M, et al. Serum ferritin as a new prognostic factor in hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with radiofrequency ablation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;29:1905-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bruix J, Sherman M. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology 2011;53:1020-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- European Association For The Study Of The Liver and European Organisation For Research And Treatment Of Cancer. EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2012;56:908-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cho HJ, Kim SS, Kang SY, et al. A Proposal for Modification of the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer Staging System Considering the Prognostic Implication of Performance Status. Gut Liver 2019;13:557-68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peng SY, Wang XA, Huang CY, et al. Better surgical treatment method for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus. World J Gastroenterol 2018;24:4527-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]