Identification of aberrantly methylated differentially expressed genes targeted by differentially expressed miRNA in osteosarcoma

Introduction

Osteosarcoma (OS) is the most common primary malignant bone tumors in children and young adults. It originates from mesenchymal cells and is characterized by the appearance of spindle cells and aberrant osteoid formation. OS can occur in any bone, although the distal femur, proximal tibia and the proximal humerus are the most common sites, accounting for respectively 43%, 23% and 10% of the cases. Within the bone, OS typically affects the metaphysis close to the growth plate (1). OS also has a high metastasis rate of 20%, and commonly invades the lungs and other bones (2).

Studies in recent years have shown that epigenetic changes play an important role in tumorigenesis and progression. DNA methylation involves addition of methyl groups (-CH3) to cytosines in the CpG dinucleotides, and both hypermethylation or hypomethylation can result in long-term silencing of imprinted genes, transposons and the inactive X chromosome (3). Aberrant methylation is frequently observed in tumors, and silencing of the promoter regions of tumor suppressor genes (TSGs) by hypermethylation of CpG islands (4) affects the cell cycle checkpoint, apoptosis, signal transduction, cell adhesion and angiogenesis genes (5). MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are short non-coding RNAs that regulate gene expression at the post-translational level by binding to the 3'-UTR of target mRNA, and are also aberrantly expressed in various cancers (6). Abnormal DNA methylation patterns have been detected in OS that interfere with the TSGs, and promote tumor initiation and progression (7). Although the DNA methylation patterns in OS have gained attention as vital biomarkers and therapeutic targets, the regulatory network between DNA methylation, miRNAs and target genes remains elusive.

Previous studies have identified several differentially methylated genes (DMGs) and differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in OS through bioinformatics analysis (8). However, the regulatory networks of OS-related miRNAs, mRNAs and methylation patterns in OS are largely unknown. To this end, we screened the mRNA, miRNA and gene methylation profiles from OS and normal bone microarray datasets, in order to identify the DEGs, DMGs, TSGs and differentially expressed miRNAs (DEMs) related to OS. The aim of our study was to identify and validate the aberrantly methylated TSGs in OS. Our findings provide new insights into the potential tumorigenic role of abnormal DNA methylation, and identify potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets for OS.

Methods

Identification of DEGs, DEMs and DMGs

The miRNA datasets GSE28423 and GSE65071, the mRNA dataset GSE36001 and the methylation dataset GSE36002 were downloaded from the GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). The GSE28423 was registered on the GPL8227 microarray platform (Agilent-019118 Human miRNA Microarray 2.0 G4470B) and contained data from 19 OS and 4 normal bone samples. GSE65071 was registered on the microarray platform of GPL19631 (Exiqon human V3 microRNA PCR panel I+II) and included data of 20 OS and 15 normal bone samples. GSE36001 and GSE36002 were from the GPL6102 microarray platform (Illumina human-6 v2.0 expression beadchip), and included data of 19 OS cell lines and 6 normal osteoblasts and bones samples.

GEO2R was used to screen for the DEGs, DEMs and DMGs from the respective datasets using |logFC| >1 or log|β| >0.2 (for DMGs) and P value <0.05 as the thresholds. The putative target genes of the overlapping DEMs of GSE28423 and GSE65071 datasets were predicted using the RNA22 tool (https://cm.jefferson.edu/rna22/Interactive/). The expression matrix of the DEGs was analyzed by the GSEA tool according to P values <0.05 and q values <0.05, and the putative TSGs were identified from the TSGene database (https://bioinfo.uth.edu/TSGene/download.cgi). Finally, the Venn diagram tool (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/) was used to determine (I) overlapping hypomethylated mRNAs, up-regulated genes and targets to identify the up-regulated hypomethylated mRNAs; (II) overlapping hypermethylated mRNAs, down-regulated mRNAs and targets for downregulated hypermethylated mRNAs; (III) overlapping down-regulated mRNAs, hypermethylated mRNAs, targets and TSGs to identify the down-regulated hypermethylated TSGs.

Functional analyses of the relevant genes

Biological process (BP) enrichment analysis and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis were performed using the ClusterProfiler package of R software, with P<0.05 as the threshold. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was conducted using the GSEA desktop tool. The Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes (STRING, https://string-db.org/) database was used to construct the PPI networks, which were then visualized using CYTOSCAPE.

Validation of TSGs

The prognostic value of the 8 TSGs was determined by survival analysis using the online database R2: Genomics Analysis and Visualization Platform (http://r2.amc.nl). The clinical data and the expression data were extracted from a dataset, the Mixed Osteosarcoma–Kuijjer–127–vst–ilmnhwg6v2. The patients were stratified into the respective low- and high-expression groups using the R2 scan method. The correlation between TSGs methylation and expression was determined by Spearman’s rank correlation analysis, with |Cor|>0.3 and P<0.05 as the thresholds.

Cell culture and treatment

The OS cell line MG63 was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA), and cultured in DMEM (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS under 5% CO2 at 37 °C. The DNA methyltransferase inhibitor 5-azacytidine (5-Aza) was purchased from MedChemExpress. The MG63 cells were treated with 5 µM 5-Aza or DMSO (vehicle) for 48 h.

RNA isolation and quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from the cells using Total RNA Extraction Reagent (Vazyme, China), and reverse transcribed into cDNA using the HiScript II Q RT SuperMix (Vazyme, China). RT-PCR was conducted using ChamQ SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme, China) in a Lightcycler 96 (Roche, Switzerland). The relative mRNA expression levels were determined by the 2-ΔΔCT method. All tests were performed three times, and GAPDH was used as the internal control. The primer sequences are shown in Table S1.

Cell proliferation assay

MG63 cells were seeded into a 96 well plate at the density of 3×103/well, and cultured with DMSO or 5-Aza for 24, 48, 72, 96 and 120 h. The medium was replaced with fresh medium supplemented with 10 µL Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) reagent/well (DOJINDO, Japan), and the cells were incubated for another hour. The absorbance at 450nm was measured using a microplate reader (Bio.Tek, USA), and the proliferation rates were calculated after subtracting the background absorbance. The experiment was performed thrice.

Wound-healing assay

MG63 cells were seeded into 6 well plates at 80% density and treated with 5 µM 5-Aza or DMSO for 48 h. The monolayer was scratched perpendicular to the plate with a sterile 200µl pipette tip. The dislodged cells were removed by washing twice with PBS, and serum-free medium was added. The cells were cultured for 24 h, and the wound edges were photographed at the same position at 0, 24 h under an inverted microscope. The migration rate was determined based on the width of the wound edges. The assay was performed in triplicate.

Invasion assay

In vitro invasion was analyzed using 24 well Invasion Chambers (8 µm pore size; Costar, Corning, USA). For the invasion assay, the transwell chambers were pre-coated with 50 µL Matrigel (Corning, USA) for 3 h. MG63 cells were seeded into the upper chambers at the density of 1×104/100 µL in serum free medium, and the lower chambers were filled with 500 µL DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. After incubating for 24 h, the cells were washed twice with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes at room temperature. The PET membranes were air-dried and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 15 minutes. The non-invaded cells were wiped off, and the invaded cells were photographed and counted under an inverted microscope in five random fields per membrane. Both assays were performed in triplicate.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using GRAPHPAD PRISM7 (GraphPad Prism Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) or SPSS 23.0. Two groups were compared using Student’s t-test with Welch correction in case of significantly different variance, or multiple groups were compared using one-way ANOVA analysis. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Identification of DEGs and DEMs in microarray

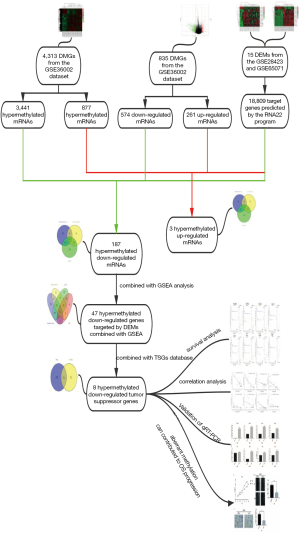

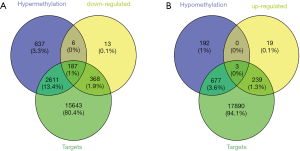

Workflow of how aberrantly methylated differentially expressed genes were identified was shown in Figure 1. A total of 15 DEMs were identified in the OS samples from the GSE28423 and GSE65071 microarray datasets (see methods), and the heat maps are shown in Figure 2A,B. In addition, 835 DEGs (Table S2) were also identified from the GSE36001 dataset, of which 574 were down-regulated and 261 were up-regulated (Figure 2C). Finally, 4,313 DMGs were detected in the GSE36002 dataset (Figure 2D), of which 3,441 were hypermethylated and 872 were hypomethylated.

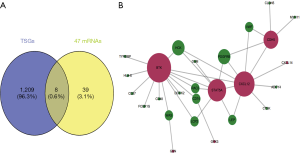

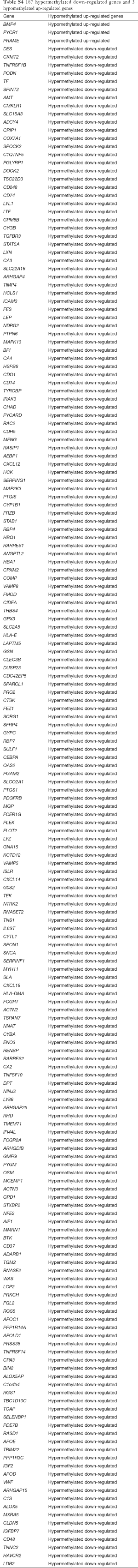

Identification of aberrantly methylated DEGs targeted by the DEMs

The RNA22 program predicted 18,809 target genes of the 15 DEMs. The overlap between these targets, DEGs and DMGs revealed 187 hypermethylated down-regulated genes (Figure 3A) and only 3 hypomethylated up-regulated genes (Figure 3B). The latter included BMP4, PYCR1 and PRAME, which are involved in BP promoting cancers and other diseases. We surmised therefore that BMP4, PYCR1 and PRAME were significant in OS progression. The DEMs and 187 hypermethylated down-regulated genes are respectively shown in Tables S3,S4.

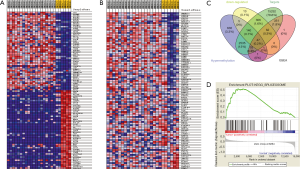

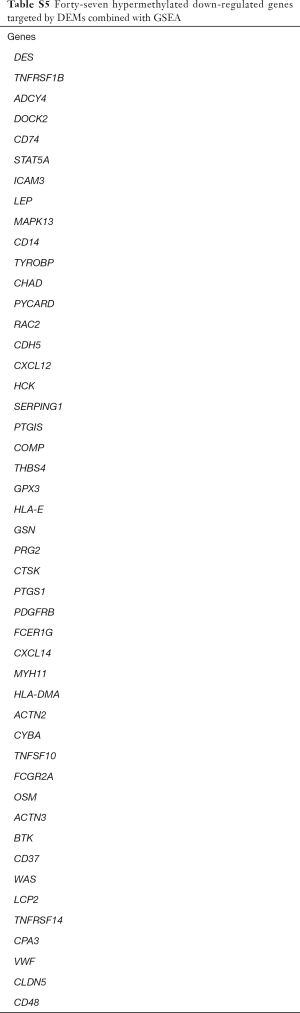

Identification of hypermethylated down-regulated genes targeted by DEMs combined with GSEA

To further identify the DEGs in OS, we conducted GSEA based on the GSE36001 dataset. Ten KEGG gene sets was significantly enriched in OS compared to normal tissues, including a total of 539 mRNAs according to P values <0.05 and q values <0.05 (Figure 4A). The most significantly enriched KEGG gene set in OS was the KEGG_SPLICEOSOME (Figure 4B), and its constituent DEGs are visualized in Figure 4C. Other significant gene sets included KEGG_CELL CYCLE and KEGG_DNA REPLICATION (Figure S1). Overlapping of the 539 mRNAs of KEGG gene sets, DEGs, DMGs and 18,809 target genes of the 15 DEMs, revealed 47 hypermethylated down-regulated genes (Figure 4D) that are likely involved in OS. The list of 47 hypermethylated down-regulated genes was shown in Table S5.

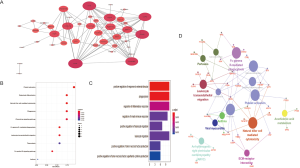

Functional enrichment analysis and PPI network construction

Gene ontology (GO) analysis and KEGG analysis were next performed to determine the BP and pathways associated with the 47 hypermethylated downregulated genes in OS (Figure 5). As shown in Figure 5C, the most enriched BP were positive regulation of response to external stimulus (GO:0032103) and phagocytosis (GO:0006909). Furthermore, KEGG pathway enrichment analysis showed that most genes were enriched in platelet activation (hsa04611), osteoclast differentiation (hsa04380), natural killer cell mediated cytotoxicity (hsa04650), phagosome (hsa04145), and chemokine signaling pathway (hsa04062). The top 10 significant pathways for the screened genes are shown in Figure 5B, indicating that the DEGs are likely involved in some osteoclast differentiation pathways and several cancer-related pathways, such as the JAK-STAT and PI3K-Akt. Furthermore, the clue GO analysis showed that MAPK13 and FCGR2A were significantly enriched in more pathways compared to the other DEGs (Figure 5D). The PPI network further showed 40 nodes with strong correlations and 2 nodes with weak correlations (Figure 5A), indicating complex interactions between the downregulated and hypermethylated mRNAs at the protein level.

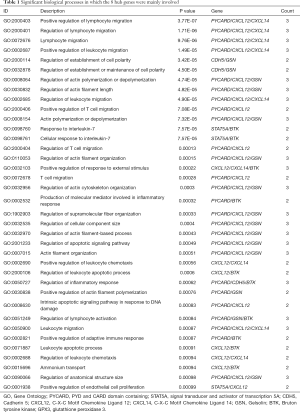

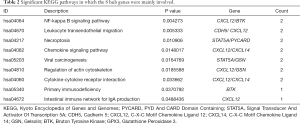

Function analysis and PPI network construction of aberrantly methylated TSGs involved in OS

Our previous study showed that down-regulated hypermethylated mRNAs play an important role in tumorigenesis. Therefore, we screened for known TSGs among the 47 OS-related DEGs, and identified eight (Figure 6A). This indicated that aberrant methylation of these TSGs downregulated their expression levels in OS and promoted tumorigenesis. PPI network construction showed that 7 down-hypermethylated TSGs were strongly correlated at the protein level (Figure 6B). Further GO analysis showed that the key genes were mainly associated with cell regulation, migration and apoptosis (Table 1), and pathway enrichment analysis indicated that they were significantly enriched in the NF-kappa B signaling pathway, chemokine signaling pathway and viral carcinogenesis (Table 2). Therefore, these aberrantly methylated TSGs are likely involved in OS progression, and are potential biomarkers.

Full table

Full table

Prognostic assessment of the down-regulated hypermethylated TSGs in OS

To determine the prognostic value of the above 8 TSGs in OS, we assessed the metastasis free survival of patients from the dataset, Mixed OS (Mesenchymal)–Kuijjer–127–vst–ilmnhwg6v2, after stratifying them into the respective low- and high-expressing groups. Patients expressing low levels of BTK, GPX3, CXCL12, CXCX14, PYCARD and STAT5A had worse metastasis free survival compared to the corresponding high expression groups (Figure 7), indicating that these genes have a significant impact on patient prognosis.

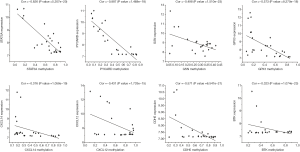

Correlation between methylation and gene expression

Correlation analysis of the gene expression and DNA methylation data revealed a significant inverse correlation between DNA methylation and the respective gene expression levels (Figure 8). The methylation sites and correlation coefficient of the significant TSGs are shown in Table 3. The most significant effect of DNA methylation was seen on the expression levels of STAT5A and PYCARD (Cor =−0.826, P value =5.207e-20; Cor =−0.887, P value =1.468e-18).

Full table

Inhibition of DNA methylation can upregulate the key genes

To further validate the impact of methylation on the expression of the TSGs, we treated MG63 cells with the methyltransferase inhibitor 5-Aza, and examined the expression levels of the relevant genes. As shown in Figure 9, PYCARD, STAT5A, CDH5, CXCL12 and CXCL14 mRNA levels were significantly increased after 5-Aza treatment, thereby confirming the in silico data. In contrast, BTK and GPX3 expression was not significantly affected by inhibiting DNA methylation.

Aberrant methylation contributed to OS progression

The findings so far indicated that methylated TSGs were involved in cancer-related pathways and contributed to OS progression. To further elucidate the effect of aberrant methylation on OS progression, the MG63 cells were treated with 5-Aza and various functional assays were performed. Blocking DNA methylation not only decreased the survival of the OS cells in vitro (Figure 10A), but also markedly diminished their migration (Figure 10B) and invasion capacities (Figure 10C) compared to the DMSO controls. Taken together, aberrant DNA methylation is conducive to OS progression, and inhibiting DNA methyltransferases can decrease proliferation, migration and invasion of OS cells.

Discussion

OS is a primary bone malignancy with a high rate of recurrence. Despite advancements in surgery and chemotherapy, the overall survival rates have been dismal over the past 20 years (9). Aberrant DNA methylation is an epigenetic modification that is frequently observed in most cancers, and is a major risk factor that drives tumorigenesis via gene silencing (7). Since epigenetic modifications affect gene functions without altering the DNA sequence, they result in more diverse gene expression profiles (10). Novel molecular biology techniques and bioinformatics integration analysis in recent years have enabled identification of aberrant methylation patterns in various cancers, and provided insights into the underlying mechanisms.

We identified 187 hypermethylated genes and 3 hypomethylated genes in OS based on mRNA, miRNA and methylation datasets, along with 15 DEMs that are relevant in OS and other cancers except has-miR-331-5p (11). The hsa-miR-142-5p (12), hsa-miR-338-3p (13) and hsa-miR-542-5p were in particular strongly associated with OS, and can help identify the key genes involved in OS progression.

BMP4, PYCR1 and PRAME were the 3 hypomethylated upregulated genes in OS. BMP4 is a secreted ligand of the TGF-β superfamily that recruits and activates SMAD family transcription factors, and is involved in cardiac development and adipogenesis (14). BMP4 promoter hypomethylation is associated with worse prognosis in gastric cancer (15), indicating that the aberrant methylation of BMP4 in OS is likely oncogenic. PYCR1 catalyzes NAD(P)H-dependent conversion of pyrroline-5-carboxylate to proline during cell proliferation and metabolism, and is up-regulated in a wide range of cancers. Overexpression of PYCR1 contributes to poor prognosis in prostate cancer (16), and based on our results, may have a pro-tumorigenic role in OS. PRAME is overexpressed in melanoma, myeloid leukemia, neuroblastoma (17), and head and neck cancer, and its hypomethylated form promotes the progression of chronic myeloid leukemia (18). In OS as well, PRAME overexpression is associated with poor prognosis, and increases tumor cell proliferation by attenuating cell cycle arrest (19). Taken together, these genes likely promote OS progression, although the underlying mechanisms need to be elucidated. Furthermore, they are potential prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets in OS.

Forty-seven hypermethylated down-regulated genes in OS were enriched in functions like response to external stimulus, cell migration and cell proliferation, chemotaxis and inflammatory response, all of which contribute to tumor metastasis (20). Aberrant migration and proliferation is an important cellular program in tumors, and are mediated by dysregulated signaling pathways (21). KEGG analysis revealed that the OS-related hypermethylated genes were significantly associated with the PI3K-Akt and JAT-STAT pathways. The former is the most frequently mutated network in human cancers, and is also dysregulated in tumors due to methylation (22). It promotes cancer cell survival by inhibiting pro-apoptotic and activating anti-apoptotic genes, Furthermore, the downstream mTOR kinase also promotes cell growth and protein synthesis, and downregulates this pathway through a feedback loop. Constitutive activation of the PI3K-Akt pathway is often accompanied by loss or mutations in the tumor suppressor PTEN (23). It also plays a critical role in OS genesis by inhibiting apoptosis and activating pro-survival pathways (24). The JAK/STAT pathway is also dysregulated in many solid tumors and increases tumor cell proliferation and angiogenesis, resulting in worse prognosis (25). Tyrosine phosphorylation and nuclear localization of the STATs have been observed in the tumor tissues across a range of cancers, indicating that JAK/SAT activation correlates with worse prognosis. We next established a clue GO network of the hypermethylated genes and these pathways, and observed significant enrichment of MAPK13 and FCGR2A. The latter is an IgG receptor, and methylation of its promoter decreases binding affinity to the human IgG2, which is associated with higher susceptibility to Kawasaki Disease (26). The p38 MAP kinase MAPK13 is aberrantly expressed in several tumors, and its promoter methylation contributes to melanoma progression (27). However, the role of MAPK13 and FCGR2A in OS remains to be elucidated.

The hypermethylated downregulated genes included 8 TSGs—CDH5, BTK, GPX3, PYCARD, CXCL12, CXCL14, STAT5A and GSN. PYCARD is a signaling factor consisting of a PYD and CARD domain, and mediates the apoptotic pathway by activating caspases (28). Studies show that hypermethylation-mediated silencing of PYCARD enables tumor cell survival by blocking apoptosis (29). We showed a strong correlation between PYCARD hypermethylation and down-regulation in OS, and verified that its low expression levels indicated worse prognosis based on clinical data. Furthermore, 5-Aza treatment markedly upregulated PYCARD, which strongly suggests that the aberrant methylation of PYCARD drives OS genesis. CXCL12 is a chemokine of the intercrine family, and binds with CXCR4 to initiate divergent pathways related to chemotaxis and cell survival (30). High expression levels of CXCL12 is associated with poor prognosis in ovarian cancer (31), and increased migration and invasiveness of adamantinomatous craniopharyngiomas (32). In contrast, down-regulation of CXCL12 have also been detected in OS via promoter hypermethylation by DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) (33). According to our findings, low expression and hypermethylation of CXCL12 indicates worse prognosis in OS, which make it a potential therapeutic target. CXCL14 is another chemokine involved in immunoregulatory and inflammatory processes (34), as well as tumor migration and invasion. It inhibited colorectal cancer cell migration by suppressing NF-kB signaling, whereas hypermethylation-mediated silencing promoted migration (35). BTK is a component of the Toll-like receptors (TLR) pathway, and promotes inflammatory responses (36). In addition, it is a modulator of p53 that can be induced in response to DNA damage and p53 activation, and phosphorylates the latter to enhance apoptosis (37). We found that low expression levels of BTK due to hypermethylation was associated with poor prognosis in OS.

CDH5 belongs to the cadherin superfamily, and is involved in the vasculogenic mimicry of glioblastoma stem-like cells under hypoxic conditions (38). Low expression levels of CDH5 mediated by promoter methylation was strongly associated with poor overall survival in neuroblastomas (39). In agreement with this, CDH5 was expressed at low levels in OS tissues compared to normal samples, and predicted poor prognosis. STAT5A is a transcription factor that is frequently dysregulated in cancer. Methylation-dependent promoter region silencing of STAT5A inhibited NPM1-ALK expression in ALK + TCL cell lines (40). One study reported low levels of STAT5A in OS and correlated it with increased tumor progression and worse overall survival (41). Consistent with this, the hypermethylation status of STAT5A was strongly associated with its low expression levels as well as poor prognosis in our study. Interestingly, BTK, CXCL12, CDH5 and STAT5A showed strong functional connectivity at the protein level, although the molecular mechanisms remain to be elucidated.

GPX3 is a glutathione peroxidase that protects cells against ROS and DNA damage, and is an established tumor suppressor in various cancers (42). Gene silencing of GPX3 by promoter hypermethylation has been reported in hepatocellular carcinoma (43), and similar trends were observed in the OS samples as well. GSN is an actin-binding protein that regulates actin filament formation and disassembly, as well as apoptosis via DNase I binding and release (44). GSN downregulation via promoter methylation predicts poor survival in gastric cancer (45), whereas overexpression of GSN promoted growth and invasion of OS cells (46). This contradicts our findings that hypermethylation and down regulation of GSN likely drive OS progression.

To summarize, we identified several TSGs that were hypermethylated and downregulated in the OS tissues, indicating a strong relationship between DNA methylation and tumorigenesis. Although our findings have to be validated in experimental studies and the underlying mechanisms also need to be elucidated, we can conclude that the aforementioned genes are significantly involved in OS progression, and are potential prognostic markers and/or therapeutic targets. There are however several limitations in this study. Since the CpG sites information was not available, the significance of specific methylation sites of these hub genes could not be determined. Furthermore, we did not correlate the expression data with the clinical parameters in the same datasets. Further studies are needed to validate the role of these TSGs in OS.

Conclusions

We identified 47 hypermethylated down-regulated mRNAs targeted by significant miRNAs in OS, of which 8 are established tumor suppressors. The aberrantly methylated TSGs may be the potential prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets for OS. Our findings provide new insights into the role of methylation in OS progression.

Full table

Full table

Full table

Full table

Full table

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the GEO databases for the availability of the data.

Funding: This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number 81572628, 81372869), The Science and Technology Project of Guangzhou (Grant No. 201704020033) and The Science and Technology Project of Tianhe District, Guangzhou (Grant No. 201604KW012).

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Gill J, Ahluwalia MK, Geller D, et al. New targets and approaches in osteosarcoma. Pharmacol Ther 2013;137:89-99. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yan GN, Lv YF, Guo QN. Advances in osteosarcoma stem cell research and opportunities for novel therapeutic targets. Cancer Lett 2016;370:268-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu SC, Zhang Y. Active DNA demethylation: many roads lead to Rome. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2010;11:607-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cui J, Wang W, Li Z, et al. Epigenetic changes in osteosarcoma. Bull Cancer 2011;98:E62-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Suzuki H, Maruyama R, Yamamoto E, et al. DNA methylation and microRNA dysregulation in cancer. MOL ONCOL 2012;6:567-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhuang M, Qiu X, Cheng D, et al. MicroRNA-524 promotes cell proliferation by down-regulating PTEN expression in osteosarcoma. Cancer Cell Int 2018;18:114. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li X, Lu H, Fan G, et al. A novel interplay between HOTAIR and DNA methylation in osteosarcoma cells indicates a new therapeutic strategy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2017;143:2189-200. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kresse SH, Rydbeck H, Skårn M, et al. Integrative analysis reveals relationships of genetic and epigenetic alterations in osteosarcoma. PLoS One 2012;7:e48262. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- O'Day K, Gorlick R. Novel therapeutic agents for osteosarcoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2009;9:511-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moore LD, Le T, Fan G. DNA Methylation and Its Basic Function. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013;38:23-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xie B, Ding Q, Han H, et al. miRCancer: a microRNA-cancer association database constructed by text mining onliterature. Bioinformatics 2013;29:638-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jones KB, Salah Z, Del Mare S, et al. miRNA Signatures Associate with Pathogenesis and Progression of Osteosarcoma. Cancer Res 2012;72:1865-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cao R, Shao J, Hu Y, et al. microRNA-338-3p inhibits proliferation, migration, invasion, and EMT inosteosarcoma cells by targeting activator of 90 kDa heat shock protein ATPasehomolog 1. Cancer Cell Int 2018;18:49. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gustafson B, Hammarstedt A, Hedjazifar S, et al. BMP4 and BMP Antagonists Regulate Human White and Beige Adipogenesis. Diabetes 2015;64:1670-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ivanova T, Zouridis H, Wu Y, et al. Integrated epigenomics identifies BMP4 as a modulator of cisplatin sensitivity in gastric cancer. Gut 2013;62:22-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zeng T, Zhu L, Liao M, et al. Knockdown of PYCR1 inhibits cell proliferation and colony formation via cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in prostate cancer. Med Oncol 2017;34:27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oberthuer A, Hero B, Spitz R, et al. The tumor-associated antigen PRAME is universally expressed in high-stage neuroblastoma and associated with poor outcome. Clin Cancer Res 2004;10:4307-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Roman-Gomez J, Jimenez-Velasco A, Agirre X, et al. Epigenetic regulation of PRAME gene in chronic myeloid leukemia. Leuk Res 2007;31:1521-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tan P, Zou C, Yong B, et al. Expression and prognostic relevance of PRAME in primary osteosarcoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2012;419:801-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lu H, Ouyang W, Huang C. Inflammation, a key event in cancer development. Mol Cancer Res 2006;4:221-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhou N, Si Z, Li T, et al. Long non-coding RNA CCAT2 functions as an oncogene in hepatocellular carcinoma, regulating cellular proliferation, migration and apoptosis. Oncol Lett 2016;12:132-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chang L, Graham PH, Ni J, et al. Targeting PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in the treatment of prostate cancer radioresistance. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2015;96:507-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stemke-Hale K, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Lluch A, et al. Integrative genomic and proteomic analysis of PIK3CA, PTEN, and AKT mutations in breast cancer. Cancer Res 2008;68:6084-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang J, Yu XH, Yan YG, et al. PI3K/Akt signaling in osteosarcoma. Clin Chim Acta 2015;444:182-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lai SY, Johnson FM. Defining the role of the JAK-STAT pathway in head and neck and thoracic malignancies: Implications for future therapeutic approaches. Drug Resist Updat 2010;13:67-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kuo HC, Hsu YW, Wu MS, et al. FCGR2A Promoter Methylation and Risks for Intravenous Immunoglobulin Treatment Responses in Kawasaki Disease. Mediators Inflamm 2015;2015:564625. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gao L, Smit MA, van den Oord JJ, et al. Genome-wide promoter methylation analysis identifies epigenetic silencing of MAPK13 in primary cutaneous melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 2013;26:542-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McConnell BB, Vertino PM. Activation of a caspase-9-mediated apoptotic pathway by subcellular redistribution of the novel caspase recruitment domain protein TMS1. Cancer Res 2000;60:6243-7. [PubMed]

- Conway KE, McConnell BB, Bowring CE, et al. TMS1, a novel proapoptotic caspase recruitment domain protein, is a target of methylation-induced gene silencing in human breast cancers. Cancer Res 2000;60:6236-42. [PubMed]

- Teicher BA, Fricker SP. CXCL12 (SDF-1)/CXCR4 Pathway in Cancer. CLIN Cancer Res 2010;16:2927-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guo Q, Gao BL, Zhang XJ, et al. CXCL12-CXCR4 Axis Promotes Proliferation, Migration, Invasion, and Metastasis of Ovarian Cancer. Oncol Res 2014;22:247-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yin X, Liu Z, Zhu P, et al. CXCL12/CXCR4 promotes proliferation, migration, and invasion of adamantinomatous craniopharyngiomas via PI3K/AKT signal pathway. J Cell Biochem 2019;120:9724-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li B, Wang Z, Wu H, et al. Epigenetic Regulation of CXCL12 Plays a Critical Role in Mediating Tumor Progression and the Immune Response In Osteosarcoma. Cancer Res 2018;78:3938-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schwarze SR, Luo J, Isaacs WB, et al. Modulation of CXCL14 (BRAK) expression in prostate cancer. Prostate 2005;64:67-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cao B, Yang Y, Pan Y, et al. Epigenetic Silencing of CXCL14 Induced Colorectal Cancer Migration and Invasion. Discov Med 2013;16:137-47. [PubMed]

- Liu X, Zhan Z, Li D, et al. Intracellular MHC class II molecules promote TLR-triggered innate immune responses by maintaining activation of the kinase Btk. Nat Immunol 2011;12:416-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Althubiti M, Rada M, Samuel J, et al. BTK Modulates p53 Activity to Enhance Apoptotic and Senescent Responses. Cancer Res 2016;76:5405-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mao XG, Xue XY, Wang L, et al. CDH5 is specifically activated in glioblastoma stemlike cells and contributes to vasculogenic mimicry induced by hypoxia. Neuro Oncol 2013;15:865-79. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fujita T, Igarashi J, Okawa ER, et al. CHD5, a tumor suppressor gene deleted from 1p36.31 in neuroblastomas. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100:940-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang Q, Wang H, Liu X, et al. STAT5A is epigenetically silenced by the tyrosine kinase NPM1-ALK and acts as a tumor suppressor by reciprocally inhibiting NPM1-ALK expression. NAT MED 2007;13:1341-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guo Z, Tang Y, Fu Y, et al. Decreased expression of STAT5A predicts poor prognosis in osteosarcoma. PATHOL RES PRACT 2019;215:519-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barrett CW, Ning W, Chen X, et al. Tumor suppressor function of the plasma glutathione peroxidase gpx3 in colitis-associated carcinoma. Cancer Res 2013;73:1245-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cao S, Yan B, Lu Y, et al. Methylation of promoter and expression silencing of GPX3 gene in hepatocellular carcinoma tissue. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2015;39:198-204. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yeh YL, Hu WS, Ting WJ, et al. Hypoxia Augments Increased HIF-1α and Reduced Survival Protein p-Akt in Gelsolin (GSN)-Dependent Cardiomyoblast Cell Apoptosis. Cell Biochem Biophys 2016;74:221-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang HC, Chen CW, Yang CL, et al. Tumor-Associated Macrophages Promote Epigenetic Silencing of Gelsolin through DNA Methyltransferase 1 in Gastric Cancer Cells. Cancer Immunol Res 2017;5:885-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ma X, Sun W, Shen J, et al. Gelsolin promotes cell growth and invasion through the upregulation of p-AKT and p-P38 pathway in osteosarcoma. Tumour Biol 2016;37:7165-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]