The global significance of China’s cancer burden and control effort

The relationship between growing economic development and increasing cancer burden has been well recognized (1). Following three decades of economic development with unprecedented speed, the overall cancer mortality in China was estimated to have increased 83%, lung cancer mortality in particular rose 465% (2). With nearly 1.4 billion population, China plays a significant role in the global cancer burden and cancer control effort. However, accurate assessment of China’s cancer burden was difficult, due to lack of a population-based cancer registry system in China, until recent years.

In 2008, the National Central Cancer Registry (NCCR) was established in China, highlighting the Chinese government’s recognition of the need and commitment to cancer control (3,4). Since then, the NCCR has been expanding with an impressive pace, from 43 registries in 2008 to 249 in 2013 covering 260 million (20% of total) population in China. And the expansion continues across the country.

The recently published “Report of cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2010” by Chen et al. (5) offered a comprehensive documentation on the development of the cancer registry system in China and provided national cancer incidence and mortality count and rate estimates for China in 2010 using NCCR data. With the nationwide age-standardized rate (ASR, World standard population, per 100,000 person-years) and count estimates of cancer incidence and mortality, this report allows a glimpse of China’s cancer burden in comparison with the worldwide estimates previously published by Ferlay et al. using GLOBOCAN 2008 data (6). Although there is a 2-year difference in time of the two assessments (China NCCR 2010 vs. GLOBOCAN 2008), the ability to examine comparable, population-based cancer information for two important geographies within a short period of time can still provide valuable understanding of cancer control needs in China and their worldwide impact.

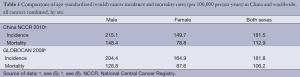

For males and females combined, the incidence ASR in China was quite similar to that of the world (181.5 vs. 181.8, Table 1), yet the mortality ASR in China was higher (112.9 vs. 106.2, Table 1). While Chinese men had higher ASRs in both incidence (215.1 vs. 204.4, Table 1) and mortality (148.4 vs. 128.8, Table 1), Chinese women displayed lower risk than women of the world in either incidence (149.7 vs. 164.9, Table 1) or mortality (78.8 vs. 87.6, Table 1).

Full table

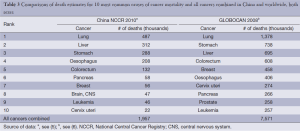

China overlapped with the world’s top 10 most common cancers (Table 2) and top 10 most common causes of cancer deaths (Table 3). However the composition and ranking of the top 10 cancers by number of annual cases or deaths differed noticeably. Cancers of brain and CNS (central nervous system), uterus, and ovary ranked as the 7th, 9th, and 10th most common cancers in China respectively, but they were not among the top 10 in the world (Table 2). prostate, bladder, and non-hodgekin’s lymphoma (NHL) cancers were the 5th, 9th and 10th most common in the world, but were not included in the Chinese top 10 list (Table 2). Although both pancreatic cancer and leukemia were not in the 10 most common cancer list for China or the world (Table 2), they both were included in the top 10 causes of cancer deaths for both locations (Table 3). Lung cancer is the number one of cancer incidence and mortality both in China and in the World, responsible for 20% of cancer cases (606,000 out of 3,093,000 Table 2) and 25% cancer deaths (487,000 out of 1,957,000, Table 3) in China, as well as 13% cancer cases (1,608,000 out of 12,677,000, Table 2) and 18% of cancer deaths (1,378,000 out of 7,571,000, Table 3) worldwide.

Full table

Full table

A large proportion of the world’s cancer burden occurred in China. Overall, about 24% of the world’s cancer diagnoses (3,093,000 out of 12,677,000, Table 2) and 26% of the world’s cancer deaths happened in China (1,957,000 out of 7,571,000, Table 3). Specifically, China’s significant shares of the world’s cancer burden include: 60% oesophagus, 48% liver, 41% stomach, 38% lung, and 22% colorectum in incidence cases; 51% oesophagus, 45% liver, 39% stomach, 35% lung, 22% colorectum, and 22% pancreas in cancer deaths.

These numbers underline the urgent need for developing effective cancer control programs in China and the significance of such programs on the worldwide effort to curb the rapidly increasing cancer incidence and mortality, especially in developing countries (7). In other words, China is obviously a major battlefield in the global fight against cancer. There are global and mutual benefits in helping China succeed in this fight.

Besides the vast number of cancer cases, the different cancer profiles between China’s rural and urban areas, as well as by its east, middle, and west regions, reflect not only the uneven economic development, but also possibly dietary and lifestyle differences in the development of cancer (5). These differences provide excellent opportunities for etiologic investigations, epidemiologic studies, and targeted outreach. China can certainly benefit from collaborating with international cancer control and research communities in these areas and contribute to building the knowledge about cancer and cancer control. Nonetheless, a well-developed population-based cancer registry system in China will provide a solid foundation and enable the aforementioned tasks.

The establishment and fast growth of NCCR are encouraging signs demonstrating the commitment to cancer control by the Chinese government that has a history of carrying out centralized effective social and public health campaigns. Participation by NCCR in projects led by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and the International Association of Cancer Registries (IACR) (5) is a wise and mutually beneficial feat that will certainly shorten the learning curve. Despite the remarkable progress the NCCR has made in its short existence, its continued development and improvement should be the top priority for China’s cancer control effort.

More important to increasing the number of NCCR registries should be to improve the quality of existing registries. Currently, data submitted by almost half of the NCCR registries were deemed as poor quality by both IARC/IACR and NCCR (5,8). Moreover, data coding and evaluation are carried out centrally by NCCR. This is understandable as a short term solution when necessary resources and expertise are lacking at the local level. However, for the long run, NCCR will need to invest in developing its own operational and data standards tailored to the health care and case-finding systems in China, and training of a competent workforce. This decentralization will not only free the central NCCR office from performing the technical routines, so it can focus more on the higher-order planning and program development, but also transform the individual registries from passive data collectors to active cancer control agents working in the communities.

Having its own evidence-based operational and data standards will define clear rules for systematic information collection and record consolidation, which will facilitate the objective and scientific evaluation of data quality. In the report by Chen et al. (5) the rather vague method of “the mortality to incidence ratio was reasonable for major cancers” was used as one of the indicators of data quality, along with a fixed values of mortality rate (e.g., Mortality rate ≥120/105 for data quality group A, ≥100/105 for group B). Data that do not meet these criteria, combined with other evaluation standards, will likely be regarded as poor quality and excluded from analysis. This practice would effectively eliminate the possibility to identify any true outliers of high or low risk areas/populations, from which important lessons/needs can be learned.

The partnership in cancer control between China and the global community is necessary. The continued, speedy but solid growth of NCCR will provide better data and tools for cancer control and research, which will benefit both China and the world.

Acknowledgements

Disclosure: The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 2005;55:74-108. [PubMed]

- Zhao P, Dai M, Chen W, et al. Cancer trends in China. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2010;40:281-5. [PubMed]

- Shen M. Prof. Wanqing Chen: The past, present and future of cancer registry in China. Ann Transl Med 2014;2:71.

- Roder D. Cancer registry data for China, 2010. Ann Transl Med 2014;2:63.

- Chen W, Zheng R, Zhang S, et al. Report of cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2010. Ann Transl Med 2014;2:61.

- Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, et al. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer 2010;127:2893-917. [PubMed]

- Stewart BW, Wild CP. eds. World Cancer Report 2014. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2014.

- Forman D, Bray F, Brewster DH, et al. eds. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents, Vol. X (electronic version) Lyon, IARC. 2013. Available online: http://ci5.iarc.fr, accessed on 6/16/2014.v