Narrative review on serous primary peritoneal carcinoma of unknown primary site: four questions to be answered

Introduction

Cancer of unknown primary (CUP) represents a heterogeneous syndrome of metastatic tumors for which a thorough workup fails to identify the primary site (1). The diagnostic advances have let to better identification of the culprit tumor which decreased the incidence of CUP from around 3–5% in the 1990s to 1–2% in the current era. However, this did not translate into a survival benefit as the patient outcomes do not differ between empiric and site-specific therapy (2,3). To date, patients with CUP are managed according to their clinicopathologic characteristics (4). The majority of patients (80–85%) have an unfavorable prognosis with a dismal survival of 3–6 months despite aggressive chemotherapy. On the other hand, the minority of patients (15–20%) which can be assigned to potential primary tumors have a favorable prognosis with a median survival of 10–16 months (4).

Serous papillary peritoneal cancer of unknown primary (SPPC) is a particular CUP entity that arises in the peritoneal surface lining the abdomen and pelvis without a discriminative primary tumor site. Autopsy studies estimate the incidence of SPPC around 1 case per 150,000 women per year and recent studies show an age-adjusted incidence rate of 0.68 per 100,000 (5,6). It was first described by Swerdow seventy-years ago in a patient that presented peritoneal carcinomatosis without any evidence of a primary tumor site (7). Patients with SPPC have a similar clinical presentation, histological features, and pattern of spread to those with primary ovarian cancer (8,9). In this review, we aim to review the validity of SPPC as a single entity as well as its biology, diagnosis, and treatment.

Materials and methods

We searched PUBMED and MEDLINE for articles published in the the English language using the following keywords: (serous papillary peritoneal cancer or carcinomatosis or tumor) or (extraovarian serous papillary cancer) or (serous papillary peritoneal carcinomatosis of unknown primary or unknown primary peritoneal cancer or carcinomatosis). We have also looked up “Peritoneal Neoplasms” (Mesh) published between 2010 and 2020. Relevant articles were assessed by two reviewers (ER and TA) for their title and abstract. The bibliography of the selected articles was also reviewed to identify studies that were missed in the initial database search. Data on clinical presentation, clinicopathology, molecular biology, management and outcome were extracted, summarized and tabulated.

Results

Question 1: does SPPC represent a single entity?

A delicate question is whether SPPC arises from the gynecologic tract similarly to primary ovarian cancer and tubal carcinomas. In 1982, Tobacman et al. reported the case of three women with SPPC occurring after prophylactic oophorectomy in the setting of a family history of ovarian cancer (10). Thus, the hypothesis supporting an exclusive origin of SPPC arising from the ovaries becomes arguable. Available data have shown that SPPC occurs more commonly in women undergoing prophylactic oophorectomy (8%) in comparison to those who have also had the fallopian tubes removed (5%) (11,12).

Primary ovarian cancer and SPPC are commonly approached as a single disease and the lack of a culprit tumor is attributed to incomplete diagnostics and uncertainty in classifying a lesion as either primary or metastasis. CUP experts do not fare better with this approach and consider primary ovarian cancer and SPPC as two separate entities. Fifteen percent of patients considered to have primary ovarian cancer in truth suffer instead of SPPC (8,9). The histopathological classification of high-grade serous carcinoma corresponding to the gene expression subtypes identified categorized primary ovarian tumors into mesenchymal transition in 34%, immune reactive in 32%, solid and proliferative in 25%, and papilla-glandular in 9%. On the other hand, SPPC is commonly assigned to the mesenchymal transition type in 75% and lack immune reactive patterns (13).

As reviewed by Sørensen et al., patients with SPPC typically share subtle clinical features that differ from those with primary ovarian cancer. Patients with SPPC may be older, have higher parity, later menarche and are more often obese (14,15). Its metastatic spread is intriguingly distinct with a high frequency of multifocal metastatic sites with diffuse micronodular involvement of the upper abdomen and diaphragmatic surfaces. The underlying different patterns of allelic loss, p53 gene mutation, and X-chromosome inactivation at different metastatic sites within the same patient support the multifocality of SPPC (16-18).

New insights into the differences in the molecular biology of SPPC and primary ovarian cancer may be accounted for the distinct natural history of the two entities. In comparison to primary ovarian cancer, SPPC has higher expression of HER2 (34–59% vs. 9–36%) (19-21) which parallels a higher proliferation index Ki-67 (38% vs. 28%) (20). It presents a lower expression of estrogen receptors (31% vs. 73%) and progesterone receptors (46% vs. 91%) (20) as well as a lower frequency of loss of heterozygosity (22). Last, it presents a similar expression level of p53 and BCL2 expression as well as microvessel density (19-21,23) and microRNA profiles (24). As such, according to this molecular pattern, SPPC and primary ovarian cancer appear to display two entities of a spectrum of disease rather than being completely distinct cancers.

Question 2: is the biology of SPPC different from that of primary ovarian cancer?

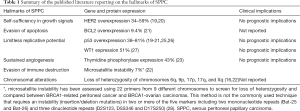

The carcinogenesis of CUP implies a clonal proliferation of normal cells acquiring multiple interdependent alterations in the cellular pathways (Table 1). Two hypotheses underlying differences in the origin and the genetic/epigenetic alterations harbored by the malignant clone are suggested to explain the carcinogenesis of SPPC. Multifocal SPPC seems to arise from any structure that embryologically derives from the Müllerian ducts, which are in close proximity to the peritoneum (29). On the other hand, unifocal SPPC supposes that the coelomic epithelium undergoes Müllerian metaplasia, namely serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma which is encountered in 45–56% of SPPC (30-32), low grade and borderline tumors (33), as a necessary precursor step to malignant transformation.

Full table

Thereafter, tumor cells migrate to the peritoneum either via the sloughed tubal cancer cells which disseminate into the peritoneal cavity or hematogenous spread with a predilection for implantation in the omentum (34). This dissemination may occur before local tumor growth according to two scenarios (35). In the first scenario which is characterized by independent genetic alterations between the primary tumor and metastatic sites (36), tumor cells alter their microenvironment and metastasize before generating a detectable tumor (37,38). In the second scenario which considers a clonal relationship between the primary and metastatic sites (39), the tumor microenvironment selectively abrogates the clonal proliferation at the primary site and favors the outgrowth of tumor cells at the metastatic sites (40,41).

Question 3: what are the diagnostic criteria in favor of SPPC?

Patients with SPPC are commonly women with a median age of 55–65 years at the time of diagnosis (42). BRCA1/2 germline mutations have been reported in 15.8–40.9% (42-46) and are commonly associated with a higher prevalence of a multifocal tumor (18). For patients with germline BRCA mutations, the lifetime risk of SPPC is 1.3% (44,47). Prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy does not seem to reduce the risk of SPPC which may occur at intervals reaching 12–84 months (44,47). Patients commonly present symptoms of peritoneal carcinomatosis such as abdominal distention and non-specific abdominal pain. It is often associated with visceral metastases that vary according to the primary tumor, disease stage, and histology (8). Sixty percent of patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis present deposits of serous papillary or poorly differentiated adenocarcinomatous histology which constitute the majority of malignant tumors arising from the ovary or fallopian tube (48). Table 2 summarizes the different diagnostic criteria suggested for the diagnosis of SPPC. The criteria of the Gynecologic Oncology Group published in 1993 are the most widely accepted and have not been revisited in the modern era (51,54).

Full table

Patients with SPPC usually undergo an extensive diagnostic workup that exceeds the minimum requirements of the ESMO recommendations which consist of basic blood tests and computed tomography scans of thorax, abdomen, and pelvis (1,4). The serum level of CA-125 does not have any significant predictive or prognostic value but can be used if the levels are initially elevated (55). Gastroscopies, colonoscopies and PET-CT scans are almost routinely performed in every single patient although they are not even recommended in the ESMO guidelines. Notably, PET-CT scan usually reveals ascites, peritoneal nodules, and omental thickening, nodularity and caking, but seldom identifies the origin of the tumor (56). Despite these diagnostic efforts, surgical diagnosis and staging remain the standard reference (57). The updated International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) classification of 2014 has uniformly classified SPPC as stage III–IV tumors depending on the disease extent and localization (57).

A pathology review of a good quality tissue sample is also required (1). SPPC resembles a papillary serous ovarian cancer being composed of complex papillary or glandular architecture (58). It presents frequent and abundant psammoma bodies (59). An initial assessment of cytokeratin 7 and 20 is the first step in identifying the culprit tumor in adenocarcinomas. The immunophenotype stains are typically positive for CK7, CD15, S-100, P53, WT-1, ER, and PAX-8 in most cases and negative for calretinin (59-63). These tumors need to be distinguished from peritoneal mesotheliomas which are negative for Ber-EP4 and MOC-31 and positive for calretinin and D2-40 (64).

Question 4: is the treatment of SPPC different from that of primary ovarian cancer?

In the absence of an identifiable primary tumor, both oncologists and patients find it hard to accept the cancer diagnosis which often delays treatment initiation. SPPC is traditionally managed according to a comprehensive treatment strategy that integrates aggressive cytoreductive surgery (CRS) to remove the macroscopic tumor, hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) to eradicate the microscopic residual disease, and systemic chemotherapy to control the microscopic metastasis. The supportive evidence is limited to retrospective series in the absence of proper randomized or prospective studies on SPPC (Tables 3,4).

Full table

Full table

The confinement of the metastatic spread of SPPC to the peritoneal cavity, the pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes constitutes a robust rationale for aggressive local control (97). A total peritonectomy (residual tumor <1–2 cm) is feasible in 13–79% of patients and should be performed to remove precursor sites and microscopic residual disease (98). Complete resection sorts out one of the most important prognostic factors affecting survival as residual tumors are reported in 60% of grossly normal-appearing peritoneum (99-101). The rates of lymph node involvement are similar between SPPC and primary ovarian tumor however the approach for lymph node dissection is different between the two entities. Systematic lymph node dissection is no longer routinely recommended in patients with primary ovarian cancer, however, it is favored in patients with SPPC (102). This discrepancy is due to the differences in the carcinogenesis of each tumor and to the workup (98). Neoadjuvant chemotherapy has been recommended to optimize local control (14,103). In a subset of 17 patients undergoing CRS following chemotherapy, the median progression-free survival was 25 months and the median OS was 48 months (82). It can be argued that patients with complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and no residual disease do not require surgical intervention. Connolly et al. reported on the outcomes of 44 patients with SPPC treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy of whom only 17 underwent CRS (82). The surgical group achieved lower recurrence rates (65% vs. 93%) and longer median progression-free survival (25 vs. 9 months; P=0.001) and median overall survival (48 vs. 18 months; P=0.0016) (82).

HIPEC is a therapeutic strategy that has developed over the past two decades and consists of delivering chemotherapy directly into the peritoneum, making it a good option for local control of peritoneal carcinomatosis (104,105). One case series of 32 patients with SPPC treated with CRS followed by HIPEC showed a 1, 3 and 5-year overall survival of 93.6%, 71.5%, and 57.4%, respectively (106). A smaller case series of 22 patients with primary SPPC (n=12) or recurrent SPPC (n=10) treated locally with CRS + HIPEC procedures yielded a 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival of 100%, 45.5%, and 27.3%, respectively. A peritoneal cancer index below 16 was the only prognostic predictor (81). Another case series of 22 patients with primary SPPC treated locally with CRS plus HIPEC showed a median disease-free survival of 32.9 months, 5-year disease-free-survival of 33.2% and 5-year overall survival of 64.9%. Serious adverse events were described in 18% of patients but there was no postoperative mortality (98).

In 2012, Pentheroudakis and Pavlidis reviewed the published series of SPPC between 1980 and 2008 and concluded to three time periods (4). Before 1990, the standard treatment which consisted of platinum- plus alkylator-based chemotherapy yielded an objective response rate of 32–80% and a median overall survival of 11–23 months. Between 1990 and 1995, platinum combinations before the taxane era achieved an objective response rate of 63–90% and a median overall survival of 14.7–25 months. After 1995, the combination of platinum/taxane yielded an objective response rate of 53–100% and a median overall survival of 15–42 months (Tables 3,4). Today, the treatment arsenal of SPPC is reinforced with bevacizumab and PARP inhibitors that were FDA approved in 2014 and 2018 respectively. These two treatment options add two milestones to the natural history of SPPC. Unfortunately, the pivotal trials as well as the retrospective case series consider primary ovarian cancers, fallopian cancers and SPPC as a single entity and do not stratify the patients’ characteristics or outcomes accordingly (107-109).

Conclusions

SPPC is almost indistinguishable from primary ovarian tumors as they share similar clinical presentation, histological features, and pattern of spread. However, it has subtle differences that render SPPC and primary ovarian cancer two entities of a spectrum of disease rather than being completely distinct cancers. The current diagnostic criteria require mainly normal-sized ovaries and extraovarian site involvement that exceeds the ovarian surface. The radiological and molecular advances have generally improved the identification rate of the primary tumor sites in patients with CUP. Namely, molecular gene profiling yielded an identification rate of 77–94% using second-generation microRNA-based assays, gene expression profiling-based microarrays tests or quantitative-PCR low-density arrays in comparison to the clinicopathologic suggestions (35). Nevertheless, these tools are not validated in patients with SPPC and require further assessments before clinical applicability.

Patients with SPPC are traditionally managed similarly to patients with stage III–IV primary ovarian cancer although they tend to have inferior outcomes. The published literature supports optimal local control in addition to systemic chemotherapy combining platinum and taxanes. In the absence of proper prospective trials, the supportive evidence is limited to retrospective series from single institutions experience in peritoneal malignancies. Whether HIPEC is of benefit or CRS can be omitted should be addressed in specifically designed trials. SPPC is not commonly distinguished as a distinct clinical entity for clinical trial inclusion and has been enrolled in ovarian cancer trials. The better understanding of the biology of SPPC permits a strict disease definition that creates a common standard diagnostic workup and a homogeneous patient population. This, in turn, will lead to more effective treatment strategies, and should also lead to the identification of novel therapeutic targets.

Acknowledgments

Funding: JSG: Funding Support provided by the National Institutes of Health grant P30 CA042014 (Ulrich, PI), GMaP Region 6, Huntsman Cancer Institute, at the University of Utah. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Stergios Boussios and Nicholas Pavlidis) for the series “Ovarian Cancer: State of the Art and Perspectives of Clinical Research” published in Annals of Translational Medicine. The article was sent for external peer review organized by the Guest Editors and the editorial office.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-941). The series “Ovarian Cancer: State of the Art and Perspectives of Clinical Research” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. SB serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Annals of Translational Medicine from Nov 2019 to Oct 2021. The other authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Fizazi K, Greco FA, Pavlidis N, et al. Cancers of unknown primary site: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2015;26 Suppl 5:v133-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hayashi H, Kurata T, Takiguchi Y, et al. Randomized Phase II Trial Comparing Site-Specific Treatment Based on Gene Expression Profiling With Carboplatin and Paclitaxel for Patients With Cancer of Unknown Primary Site. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:570-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- El Rassy E, Pavlidis N. The current evidence for a biomarker-based approach in cancer of unknown primary. Cancer Treat Rev 2018;67:21-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pavlidis N, Pentheroudakis G. Cancer of unknown primary site. Lancet 2012;379:1428-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Killackey MA, Davis AR. Papillary serous carcinoma of the peritoneal surface: matched-case comparison with papillary serous ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 1993;51:171-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goodman MT, Shvetsov YB. Incidence of Ovarian, Peritoneal, and Fallopian Tube Carcinomas in the United States, 1995-2004. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009;18:132-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Swerdlow M. Mesothelioma of the pelvic peritoneum resembling papillary cystadenocarcinoma of the ovary; case report. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1959;77:197-200. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pentheroudakis G, Pavlidis N. Serous papillary peritoneal carcinoma: unknown primary tumour, ovarian cancer counterpart or a distinct entity? A systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2010;75:27-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rothacker D, Möbius G. Varieties of serous surface papillary carcinoma of the peritoneum in northern Germany: a thirty-year autopsy study. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1995;14:310-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tobacman JK, Greene MH, Tucker MA, et al. Intra-abdominal carcinomatosis after prophylactic oophorectomy in ovarian-cancer-prone families. Lancet 1982;2:795-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Olivier RI, van Beurden M, Lubsen MAC, et al. Clinical outcome of prophylactic oophorectomy in BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation carriers and events during follow-up. Br J Cancer 2004;90:1492-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Casey MJ, Bewtra C. Peritoneal carcinoma in women with genetic susceptibility: implications for Jewish populations. Fam Cancer 2004;3:265-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ohsuga T, Yamaguchi K, Kido A, et al. Distinct preoperative clinical features predict four histopathological subtypes of high-grade serous carcinoma of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum. BMC Cancer 2017;17:580. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schnack TH, Sørensen RD, Nedergaard L, et al. Demographic clinical and prognostic characteristics of primary ovarian, peritoneal and tubal adenocarcinomas of serous histology—a prospective comparative study. Gynecol Oncol 2014;135:278-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dahm-Kähler P, Borgfeldt C, Holmberg E, et al. Population-based study of survival for women with serous cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, peritoneum or undesignated origin - on behalf of the Swedish gynecological cancer group (SweGCG). Gynecol Oncol 2017;144:167-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang LW, Garrett AP, Muto MG, et al. Identification of a novel 9 cM deletion unit on chromosome 6q23-24 in papillary serous carcinoma of the peritoneum. Hum Pathol 2000;31:367-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Muto MG, Welch WR, Mok SC, et al. Evidence for a multifocal origin of papillary serous carcinoma of the peritoneum. Cancer Res 1995;55:490-2. [PubMed]

- Schorge JO, Muto MG, Welch WR, et al. Molecular Evidence for Multifocal Papillary Serous Carcinoma of the Peritoneum in Patients With Germline BRCA1 Mutations. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst 1998;90:841-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kowalski LD, Kanbour AI, Price FV, et al. A case-matched molecular comparison of extraovarian versus primary ovarian adenocarcinoma. Cancer 1997;79:1587-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Halperin R, Zehavi S, Hadas E, et al. Immunohistochemical comparison of primary peritoneal and primary ovarian serous papillary carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2001;20:341-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen LM, Yamada SD, Fu YS, et al. Molecular similarities between primary peritoneal and primary ovarian carcinomas. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2003;13:749-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang LW, Garrett AP, Schorge JO, et al. Distinct allelic loss patterns in papillary serous carcinoma of the peritoneum. Am J Clin Pathol 2000;114:93-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Terai Y, Ueda M, Kumagai K, et al. Tumor angiogenesis and thymidine phosphorylase expression in ovarian carcinomas including serous surface papillary adenocarcinoma of the peritoneum. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2000;19:354-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pentheroudakis G, Spector Y, Krikelis D, et al. Global microRNA profiling in favorable prognosis subgroups of cancer of unknown primary (CUP) demonstrates no significant expression differences with metastases of matched known primary tumors. Clin Exp Metastasis 2013;30:431-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moll UM, Valea F, Chumas J. Role of p53 alteration in primary peritoneal carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1997;16:156-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cass I, Baldwin RL, Fasylova E, et al. Allelotype of Papillary Serous Peritoneal Carcinomas. Gynecol Oncol 2001;82:69-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schorge JO, Miller YB, Qi LJ, et al. Genetic alterations of the WT1 gene in papillary serous carcinoma of the peritoneum. Gynecol Oncol 2000;76:369-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boland CR, Thibodeau SN, Hamilton SR, et al. A National Cancer Institute Workshop on Microsatellite Instability for cancer detection and familial predisposition: development of international criteria for the determination of microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res 1998;58:5248-57. [PubMed]

- Dubeau L. The cell of origin of ovarian epithelial tumours. Lancet Oncol 2008;9:1191-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kindelberger DW, Lee Y, Miron A, et al. Intraepithelial carcinoma of the fimbria and pelvic serous carcinoma: Evidence for a causal relationship. Am J Surg Pathol 2007;31:161-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carlson JW, Miron A, Jarboe EA, et al. Serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma: its potential role in primary peritoneal serous carcinoma and serous cancer prevention. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:4160-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Seidman JD, Zhao P, Yemelyanova A. “Primary peritoneal” high-grade serous carcinoma is very likely metastatic from serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma: assessing the new paradigm of ovarian and pelvic serous carcinogenesis and its implications for screening for ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2011;120:470-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dehari R, Kurman RJ, Logani S, et al. The development of high-grade serous carcinoma from atypical proliferative (borderline) serous tumors and low-grade micropapillary serous carcinoma: a morphologic and molecular genetic analysis. Am J Surg Pathol 2007;31:1007-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pradeep S, Kim SW, Wu SY, et al. Hematogenous metastasis of ovarian cancer: rethinking mode of spread. Cancer Cell 2014;26:77-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rassy E, Assi T, Pavlidis N. Exploring the biological hallmarks of cancer of unknown primary: where do we stand today? Br J Cancer 2020;122:1124-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Joosse SA, Pantel K. Genetic traits for hematogeneous tumor cell dissemination in cancer patients. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2016;35:41-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- López-Lázaro M. The migration ability of stem cells can explain the existence of cancer of unknown primary site. Rethinking metastasis. Oncoscience 2015;2:467-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Califano J, Westra WH, Koch W, et al. Unknown primary head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: molecular identification of the site of origin. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999;91:599-604. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Speel E-JM, Wouw AJ, van de , Claessen SMH, et al. Molecular evidence for a clonal relationship between multiple lesions in patients with unknown primary adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer 2008;123:1292-300. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Suzuki M, Mose ES, Montel V, et al. Dormant Cancer Cells Retrieved from Metastasis-Free Organs Regain Tumorigenic and Metastatic Potency. Am J Pathol 2006;169:673-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tarin D. Clinical and biological implications of the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Microenviron 2012;5:95-112. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schorge JO, Muto MG, Lee SJ, et al. BRCA1-related papillary serous carcinoma of the peritoneum has a unique molecular pathogenesis. Cancer Res 2000;60:1361-4. [PubMed]

- Menczer J, Chetrit A, Barda G, et al. Frequency of BRCA mutations in primary peritoneal carcinoma in Israeli Jewish women. Gynecol Oncol 2003;88:58-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Levine DA, Argenta PA, Yee CJ, et al. Fallopian tube and primary peritoneal carcinomas associated with BRCA mutations. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:4222-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alsop K, Fereday S, Meldrum C, et al. BRCA mutation frequency and patterns of treatment response in BRCA mutation-positive women with ovarian cancer: a report from the Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:2654-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Choi MC, Bae JS, Jung SG, et al. Prevalence of germline BRCA mutations among women with carcinoma of the peritoneum or fallopian tube. J Gynecol Oncol 2018;29:e43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Iavazzo C, Gkegkes ID, Vrachnis N. Primary peritoneal cancer in BRCA carriers after prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc 2016;17:73-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Resta L, Maiorano E, Zito FA, et al. Multifocal extraovarian serous carcinoma. A histochemical and immunohistochemical study. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 1988;9:474-8. [PubMed]

- Mills SE, Andersen WA, Fechner RE, et al. Serous surface papillary carcinoma. A clinicopathologic study of 10 cases and comparison with stage III-IV ovarian serous carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1988;12:827-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fromm GL, Gershenson DM, Silva EG. Papillary serous carcinoma of the peritoneum. Obstet Gynecol 1990;75:89-95. [PubMed]

- Bloss JD, Liao SY, Buller RE, et al. Extraovarian peritoneal serous papillary carcinoma: a case-control retrospective comparison to papillary adenocarcinoma of the ovary. Gynecol Oncol 1993;50:347-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mulhollan TJ, Silva EG, Tornos C, et al. Ovarian involvement by serous surface papillary carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1994;13:120-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- NCCN Guidelines (2020). Ovarian Cancer/Fallopain Tube Cancer/Primary Peritoneal Cancer. Version 1.2020. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/ovarian.pdf. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology.

- Singh N, Gilks CB, Wilkinson N, et al. Assignment of primary site in high-grade serous tubal, ovarian and peritoneal carcinoma: a proposal. Histopathology 2014;65:149-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Iavazzo C, Vorgias G, Katsoulis M, et al. Primary peritoneal serous papillary carcinoma: clinical and laboratory characteristics. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2008;278:53-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pavlidis N, Pentheroudakis G. Cancer of unknown primary site: 20 questions to be answered. Ann Oncol 2010;21 Suppl 7:vii303-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Prat J. FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology. Staging classification for cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2014;124:1-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gibbs AR. Tumours of the Serosal Membranes. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology Atlas of Tumour Pathology, Fourth Series, Fascicle 3. Occup Environ Med 2007;64:288. [Crossref]

- Liu Q, Lin J, Shi Q, et al. Primary Peritoneal Serous Papillary Carcinoma: A Clinical and Pathological Study. Pathol Oncol Res 2011;17:713-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ben-Baruch G, Sivan E, Moran O, et al. Primary peritoneal serous papillary carcinoma: a study of 25 cases and comparison with stage III-IV ovarian papillary serous carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 1996;60:393-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Attanoos RL, Webb R, Dojcinov SD, et al. Value of mesothelial and epithelial antibodies in distinguishing diffuse peritoneal mesothelioma in females from serous papillary carcinoma of the ovary and peritoneum. Histopathology 2002;40:237-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ozcan A, Shen SS, Hamilton C, et al. PAX 8 expression in non-neoplastic tissues, primary tumors, and metastatic tumors: a comprehensive immunohistochemical study. Mod Pathol 2011;24:751-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Matsuo K, Sheridan TB, Mabuchi S, et al. Estrogen receptor expression and increased risk of lymphovascular space invasion in high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 2014;133:473-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ordóñez NG. The diagnostic utility of immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy in distinguishing between peritoneal mesotheliomas and serous carcinomas: a comparative study. Mod Pathol 2006;19:34-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lele SB, Piver MS, Matharu J, et al. Peritoneal papillary carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 1988;31:315-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Strnad CM, Grosh WW, Baxter J, et al. Peritoneal carcinomatosis of unknown primary site in women: a distinctive subset of adenocarcinoma. Ann Intern Med 1989;111:213-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ransom DT, Patel SR, Keeney GL, et al. Papillary serous carcinoma of the peritoneum. A review of 33 cases treated with platin-based chemotherapy. Cancer 1990;66:1091-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Truong LD, Maccato ML, Awalt H, et al. Serous surface carcinoma of the peritoneum: a clinicopathologic study of 22 cases. Hum Pathol 1990;21:99-110. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhou J, Iwasa Y, Konishi I, et al. Papillary serous carcinoma of the peritoneum in women. A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study. Cancer 1995;76:429-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liapis A, Condi-Paphiti A, Pyrgiotis E, et al. Ovarian surface serous papillary carcinomas: a clinicopathologic study. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 1996;17:79-82. [PubMed]

- Taus P, Petru E, Gücer F, et al. Primary serous papillary carcinoma of the peritoneum: a report of 18 patients. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 1997;18:171-2. [PubMed]

- Piver MS, Eltabbakh GH, Hempling RE, et al. Two sequential studies for primary peritoneal carcinoma: induction with weekly cisplatin followed by either cisplatin-doxorubicin-cyclophosphamide or paclitaxel-cisplatin. Gynecol Oncol 1997;67:141-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kennedy AW, Markman M, Webster KD, et al. Experience with platinum-paclitaxel chemotherapy in the initial management of papillary serous carcinoma of the peritoneum. Gynecol Oncol 1998;71:288-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morita H, Aoki J, Taketomi A, et al. Serous surface papillary carcinoma of the peritoneum: clinical, radiologic, and pathologic findings in 11 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2004;183:923-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pentheroudakis G, Briasoulis E, Karavassilis V, et al. Chemotherapy for patients with two favourable subsets of unknown primary carcinoma: active, but how effective? Acta Oncol 2005;44:155-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Choi CH, Kim T-J, Kim WY, et al. Papillary serous carcinoma in ovaries of normal size: a clinicopathologic study of 20 cases and comparison with extraovarian peritoneal papillary serous carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 2007;105:762-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang C, Li X, Cui H, Shen D, et al. Advanced primary peritoneal carcinoma: clinicopathological and prognostic factor analyses. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B 2008;9:435-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Roh SY, Hong SH, Ko YH, et al. Clinical characteristics of primary peritoneal carcinoma. Cancer Res Treat 2007;39:65-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bakkar R, Gershenson D, Fox P, et al. Stage IIIC ovarian/peritoneal serous carcinoma: a heterogeneous group of patients with different prognoses. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2014;33:302-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Usach I, Blansit K, Chen LM, et al. Survival differences in women with serous tubal, ovarian, peritoneal, and uterine carcinomas. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;212:188.e1-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sun JH, Ji ZH, Peng KW, et al. Cytoreductive surgery combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for the treatment of primary peritoneal serous carcinoma: Results of a Chinese retrospective study. Int J Hyperthermia 2016;32:289-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Connolly CF, Yahya S, Chan KK, et al. Outcomes following interval debulking surgery in primary peritoneal carcinoma. Anticancer Res 2016;36:255-9. [PubMed]

- Dalrymple JC, Bannatyne P, Russell P, et al. Extraovarian peritoneal serous papillary carcinoma. A clinicopathologic study of 31 cases. Cancer 1989;64:110-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wick MR, Mills SE, Dehner LP, et al. Serous papillary carcinomas arising from the peritoneum and ovaries. A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical comparison. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1989;8:179-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bloss JD, Liao SY, Buller RE, et al. Extraovarian peritoneal serous papillary carcinoma: a case-control retrospective comparison to papillary adenocarcinoma of the ovary. Gynecol Oncol 1993;50:347-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fowler JM, Nieberg RK, Schooler TA, et al. Peritoneal adenocarcinoma (serous) of Müllerian type: a subgroup of women presenting with peritoneal carcinomatosis. Int J Gynecol Cancer 1994;4:43-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Piura B, Meirovitz M, Bartfeld M, et al. Peritoneal papillary serous carcinoma: study of 15 cases and comparison with stage III-IV ovarian papillary serous carcinoma. J Surg Oncol 1998;68:173-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Halperin R, Zehavi S, Hadas E, et al. Immunohistochemical comparison of primary peritoneal and primary ovarian serous papillary carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2001;20:341-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bloss JD, Brady MF, Liao SY, et al. Extraovarian peritoneal serous papillary carcinoma: a phase II trial of cisplatin and cyclophosphamide with comparison to a cohort with papillary serous ovarian carcinoma—a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Gynecol Oncol 2003;89:148-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dubernard G, Morice P, Rey A, et al. Prognosis of stage III or IV primary peritoneal serous papillary carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol 2004;30:976-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khalifeh I, Munkarah AR, Lonardo F, et al. Expression of Cox-2, CD34, Bcl-2, and p53 and survival in patients with primary peritoneal serous carcinoma and primary ovarian serous carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2004;23:162-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ayhan A, Taskiran C, Yigit-Celik N, et al. Long-term survival after paclitaxel plus platinum-based combination chemotherapy for extraovarian peritoneal serous papillary carcinoma: is it different from that for ovarian serous papillary cancer? Int J Gynecol Cancer 2006;16:484-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eisenhauer EL, Sonoda Y, Levine DA, et al. Platinum resistance and impaired survival in patients with advanced primary peritoneal carcinoma: matched-case comparison with patients with epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;198:213.e1-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chao KC, Chen YJ, Juang CM, et al. Prognosis for advanced-stage primary peritoneal serous papillary carcinoma and serous ovarian cancer in Taiwan. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2013;52:81-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fukuda T, Imai K, Yamauchi M, et al. Primary peritoneal cancer: study of 14 cases and comparison with epithelial ovarian cancer. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 2015;36:49-53. [PubMed]

- Gao B, Lindemann K, Anderson L, et al. Serous ovarian and primary peritoneal cancers: A comparative analysis of clinico-pathological features, molecular subtypes and treatment outcome. Gynecol Oncol 2016;142:458-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Steinhagen PR, Sehouli J. The involvement of retroperitoneal lymph nodes in primary serous-papillary peritoneal carcinoma. a systematic review of the literature. Anticancer Res 2011;31:1387-94. [PubMed]

- Deraco M, Sinukumar S, Salcedo-Hernández RA, et al. Clinico-pathological outcomes after total parietal peritonectomy, cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in advanced serous papillary peritoneal carcinoma submitted to neoadjuvant systemic chemotherapy-largest single institute experience. Eur J Surg Oncol 2019;45:2103-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eltabbakh GH, Werness BA, Piver S, et al. Prognostic factors in extraovarian primary peritoneal carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 1998;71:230-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Unal OU, Oztop I, Yazici O, et al. Treatment and prognostic factors in primary peritoneal carcinoma: a multicenter study of the Anatolian Society of Medical Oncology (ASMO). Oncol Res Treat 2014;37:332-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Crane EK, Sun CC, Ramirez PT, et al. The role of secondary cytoreduction in low-grade serous ovarian cancer or peritoneal cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2015;136:25-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Atallah D, Rassy E, Chahine G. Is the LION strong enough? Future Oncol 2017;13:1835-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luyckx M, Leblanc E, Filleron T, et al. Maximal cytoreduction in patients with FIGO stage IIIC to stage IV ovarian, fallopian, and peritoneal cancer in day-to-day practice: a Retrospective French Multicentric Study. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2012;22:1337-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yun WS, Bae JM. Primary peritoneal serous carcinoma, an extremely rare malignancy: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett 2016;11:4063-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yuan J, He L, Han B, et al. Long-term survival of high-grade primary peritoneal papillary serous adenocarcinoma: a case report and literature review. World J Surg Oncol 2017;15:76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bakrin N, Gilly FN, Baratti D, et al. Primary peritoneal serous carcinoma treated by cytoreductive surgery combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. A multi-institutional study of 36 patients. Eur J Surg Oncol 2013;39:742-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boussios S, Karihtala P, Moschetta M, et al. Combined Strategies with Poly (ADP-Ribose) Polymerase (PARP) Inhibitors for the Treatment of Ovarian Cancer: A Literature Review. Diagn Basel Switz 2019;9.

- Boussios S, Karihtala P, Moschetta M, et al. Veliparib in ovarian cancer: a new synthetically lethal therapeutic approach. Invest New Drugs 2020;38:181-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boussios S, Abson C, Moschetta M, et al. Poly (ADP-Ribose) Polymerase Inhibitors: Talazoparib in Ovarian Cancer and Beyond. Drugs R D 2020;20:55-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]