Cyclin G2 promotes the formation of smooth muscle cells derived foam cells in atherosclerosis via PP2A/NF-κB/LOX-1 pathway

Introduction

Atherosclerosis, due to high morbidity and lethal rate, is a huge health and economic burden on society. The conversion of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) and macrophages into foam cells is an important event of early atherosclerotic lesions (1-3). Interestingly, in human coronary atherosclerosis, more than 50% of foam cells are of VSMCs origin (4). Therefore, exploring the mechanism of VSMCs-derived foam cell formation and the associated regulatory factors can offer novel therapeutic targets for atherosclerosis.

Cyclin G2, a G-type cyclin, encoded by the Ccng2 gene, inhibits G1/S phase transition of the cell cycle. It is a potential tumor suppressor that plays a negative regulatory role in a variety of tumors, such as oral cancer, gastric cancer, and glioma (5,6). Additionally, cyclin G2 promotes adipogenic differentiation, inhibits osteogenic differentiation, and regulates cytoskeleton (7,8). Obesity and osteoporosis are the major risk factors for atherosclerosis (9,10). Recently, a microarray study of coronary artery SMCs revealed that atherogenic oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL) closely correlates with the cyclin G2 expression (11). Based on this finding, we speculated that cyclin G2 might also play an important role in atherosclerosis.

VSMCs get transformed into foam cells by the phagocytosis of lipids via scavenger receptors on the cell membrane. The main scavenger receptors include scavenger receptor-A (SRA), CD36 receptor (CD36), and lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1 (LOX-1). In hyperlipidemic mice (Apoe-/-), knockout of SRA or CD36 receptors improved atherosclerotic lesions without affecting the formation of foam cells (12). Ox-LDL, an activator of LOX-1, is abundantly expressed in atherosclerotic plaques and surrounding tissues (13). The upregulation of LOX-1 on VSMCs and macrophage membranes increases the internalization of ox-LDL promoting foam cell formation (14). Interestingly, anti-LOX-1 antibodies can significantly reduce ox-LDL uptake by VSMCs and thereby inhibit the formation of foam cells (15).

The protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) is an important serine/threonine phosphatase that regulates the NF-κB signaling pathway (16). It dephosphorylates I-κBα, an inhibitor of NF-κB. Upon phosphorylation and ubiquitination of I-κBα, the released NF-κB is phosphorylated to promote LOX-1 transcription. Recently, Chen et al. showed that AMPK reduces LOX-1 expression by increasing PP2A activity and inhibiting NF-κB activation (17). Given this, we hypothesized that cyclin G2 might also affect the expression of LOX-1 via the PP2A/NF-κB signaling pathway. In the present study, we firstly investigated the effects of cyclin G2 by comparing the formation of VSMCs-derived foam cells and atherosclerotic plaques between the Apoe-/-Ccng2-/- mice and Apoe-/- mice. Then, we explored the underlying mechanism of the PP2A/NF-κB/LOX-1 pathway by carrying out a series of in vivo and in vitro experiments.

We present the following article in accordance with the ARRIVE reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-6207).

Methods

Establishment of atherosclerosis model and grouping

The animal experiments were approved by the Ethics Review Committee of China Medical University (IACUC NO. 201903153). All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed. 8 weeks old male Apoe-/- mice and Apoe-/-Ccng2-/- mice were selected and divided (10 each) into control and experimental groups respectively. The double gene knockout mice were obtained by cross-breeding of Apoe-/- mice and Ccng2-/- mice. Animals were maintained at room temperature (RT: 20–25 °C) with 12 hours of day and night cycle, having water ad libitum. The two groups of mice were fed a high-fat diet (Huafukang Biological Company, Beijing, China) for 8 weeks to construct the atherosclerosis model. Before the experiment, mice were deprived of water for 12 hours. Mice body weight was measured. Mice were anesthetized using 50 mg/kg pentobarbital sodium. Mice blood samples were collected from the orbital venous plexus and after standing for 1 hour, samples were centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 minutes. The supernatant was stored at −80 °C. For aorta isolation, a small cut was made in the left atrial appendage; the apex was punctured and perfused with PBS. The abdominal aorta and thoracic aorta were separated from the iliac artery to the heart. The lipids on the aortic blood vessel’s outer surface were cleaned, and then the blood vessel was cut to spread. The tissues were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 hours and stored at 4 °C.

Detection of blood lipid index in mice

Total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels in mice were measured using the AU5400 automatic biochemical analyzer (OLYMPUS, Tokyo, Japan).

Oil red O staining

Before the oil red O staining (Sigma, LA, USA, at 37 °C for 30 minutes), tissues were dehydrated with 100% isopropanol for 5 minutes. Post staining, non-specific Oil red O stain was removed by rinsing with 60% isopropyl alcohol, and residual isopropyl alcohol was removed. Finally, stained blood vessels were observed using a digital camera (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). In both groups of mice, the microscopic observation showed that there was no rupture in the blood vessel plaques. Also, during the experiment, mice did not suffer from cardiovascular events such as acute myocardial infarction and sudden death. The MOVAS cells were stained as described previously (18).

H&E staining

The heart, vertically fixed on a frozen microtome, was sliced (8 µm thickness) from the aortic root to the apex. The frozen sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes and washed with ddH2O for 2 minutes. After differentiating with 60% isopropanol for 10 seconds, the Oil Red O dyeing solution (Sigma, LA, USA) was added at RT for 15 minutes. Over stain was washed using 60% isopropyl alcohol for 5 seconds. The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin stain (Solarbio, Beijing, China) for 30 seconds. After washing with tap water for 2 minutes, the slides were mounted with glycerin and gelatin. Finally, pictures were obtained using a digital camera (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunohistochemical staining

The paraffin sections were soaked in xylene, 100% ethanol, 95% ethanol, 90% ethanol, 80% ethanol, and 70% ethanol in an orderly fashion. The paraffin sections were inactivated for endogenous peroxidase with 3% H2O2 in a wet box for 10 minutes and washed twice with PBS. Then, the tissue slices were repaired with 0.1 M sodium citrate solution. After incubating with blocking solution for 30 minutes, the tissue sections were overnight incubated with proportionally diluted primary antibodies at 4 °C. Next, secondary antibody (ZSGB-BIO, Beijing, China) was added and incubated at 37 °C for 30 minutes, followed by washing with PBS for 5 minutes 3 times. Lastly, the sections were stained with dimethylbenzidine (DAB) at room temperature.

Cell culture and experimental grouping

MOVAS cell line (mouse aortic root vascular smooth muscle cell line) was obtained from ATCC (MD, USA) and cultured in DMEM (GIBCO, LA, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma, CA, USA). The cells were transfected with constructs p3×Flag-CMV-Ccng2 or empty plasmid p3×Flag-CMV-14. These were labeled as experimental group (FLAG-Ccng2) and control group (FLAG-Vector) correspondingly. In MOVAS cells, foaming was induced using 80 µg/mL ox-LDL (Yi-yuan, Guangzhou, China) for 24 hours. The PP2A activator DT-061 (MedChemExpress, CA, USA), at a dose of 20 µM or equal volume of DMSO (Sigma, CA, USA), was added to respective groups and these were denoted as FLAG-Vector + DMSO, FLAG-Ccng2 + DMSO, FLAG-Ccng2 + DT-061, and FLAG-Vector + DT-061 groups respectively.

Plasmid extraction and transfection

The plasmid was extracted according to the manufactures’ instructions (Invitrogen, CA, USA) and stored at 4 °C. MOVAS cells, with 30–50% density, were seeded on a 6-well plate. One µg/µL of plasmid was transfected using the Polyplus solution. Then, the transfected cells were cultured for 6 hours and the medium was freshly replaced after 18 hours. The cells were cultured in a serum-free medium and starved for 24 hours.

Detection of intracellular total cholesterol

The cells were scraped on ice and centrifuged at 1,500 rpm for 5 minutes. Then, these were washed twice with PBS and again centrifuged to obtain the cell mass. The cell lysis was performed on ice with 2% TritonX-100 for 30 minutes. The standard substance, sample, and working solution were mixed well and incubated at 37 °C for 10 minutes. The absorbance of lysates was measured at 510 nm. The lysed liquid was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 20 minutes at 4 °C. The protein concentration of the supernatants was determined by the BCA method. The following formula was used: total cholesterol content (mmol/gprot) = (sample OD value − blank OD value)/(calibration OD value − blank OD value) × 2.26/protein concentration.

Total RNA extraction and qRT-PCR

Total cell RNA was extracted using Trizol lysis buffer (Invitrogen, CA, USA) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA concentration was measured and reverse transcription to cDNA was performed using the PrimeScript RTreagent Kit (Takara, Tokyo, Japan). The real-time quantitative PCR analysis was performed using a 20 µL reaction system (Takara, Tokyo, Japan). GAPDH was used for normalization. The sequences of the used primers were as follows: LOX-1 Forward: GCTGCAAACTTTTCAGGTCCT; LOX-1 Reverse: GTGGTATGGGAAATTGCTTGTAAG; GAPDH Forward: GCACACAGTACATCCGTCA; GAPDH Reverse: TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT.

Western blotting

The cells were lysed on ice using the RIPA lysis buffer (Solarbio, Beijing, China) containing 10% protease inhibitor (Invitrogen, CA, USA) and 1% phosphatase inhibitor (Invitrogen, CA, USA). The lysates were centrifuged at 4 °C, 12,000 rpm for 25 minutes. The supernatant was subjected to protein quantification using the BCA protein quantification kit (Invitrogen, CA, USA). The nuclear protein extraction was performed using Minute TM Cytoplasmic Nuclear Separation Kit (Invitrogen, CA, USA) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The primary antibodies used for western blotting were as follows: p-NF-κB (Cell Signaling Technology, CA, USA), NF-κB (Sabbiotech, LA, USA), LOX-1 (R&D Systems, CA, USA), α-SMA (Servicebio, Wuhan, China), CD68 (Servicebio, Wuhan, China), GAPDH (Santa Cruz, LA, USA), PCNA (Wangleibio, Shenyang, China).

Dil-oxLDL uptake assay

After 24 hours of starvation, MOVAS cells were incubated with 20 µg/mL Dil-oxLDL (Yi-yuan, Guangzhou, China) for 6 hours. Then, the cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at RT for 30 minutes. The cell membrane was made permeable after treating with 0.03% TritonX-100 for 20 minutes. The nuclei were stained with DAPI for 5 minutes. For each sample, 5 distinct fields of view were selected and pictures were obtained using an inverted fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunofluorescence staining

The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at RT for 30 minutes and washed with PBS. Like earlier, 0.03% TritonX-100 was used to increase the cell membrane permeability. Then, the cells were incubated with donkey serum and blocking was performed for 1 hour. Next, overnight incubation with the p-NF-κB primary antibodies (Abcam, CA, USA) was carried out at 4 °C in the dark. This was followed by incubation with the corresponding secondary antibodies for 1 hour. Finally, the nuclei were stained with DAPI for 5 minutes and 5 distinct fields of view for each sample were selected for analysis. Pictures were obtained with an inverted fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

PP2A activity test

The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 20 minutes and the cell lysates were prepared. The protein concentration was measured using the BCA method. Then, 10 µL cold phosphatase storage buffer was added and samples were centrifuged at 4 °C 600 rpm for 5 minutes. The spin-column was put into a 50 mL centrifuge tube, 250 µL cell lysate was added and centrifuged at 4 °C 600 rpm for 5 minutes. The PP2A reaction buffer, phosphate standard, substrate peptide, and the protein sample were mixed to the 96-well plate and reacted at 37 °C for 30 minutes. Finally, 50 µL molybdate dye was added to stop the reaction for 30 minutes at RT and the absorbance was measured at 630 nm. The relative activity was calculated using a standard concentration curve.

Statistical analysis

Image-Pro Plus 6.0 and Graphpad Prism 7.0 programs were used for image processing. All data were analyzed using SPSS 22.0 statistical software and are presented as mean ± SD. The comparison within the group was performed by the one-way analysis of variance, and the comparison between the two groups was performed by the student’s t-test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All experiments were carried out three times.

Results

Ccng2 knockout attenuated atherosclerotic plaques in Apoe-/- mice

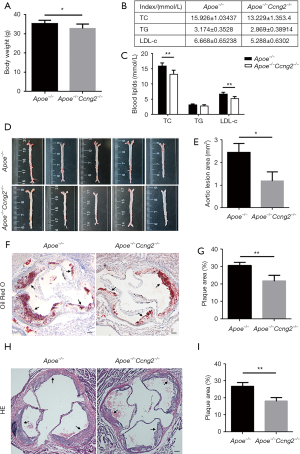

Apoe-/- mice and Apoe-/-Ccng2-/- mice were fed with a high-fat diet for 8 weeks to establish the atherosclerosis model. Notably, compared to Apoe-/- mice, Apoe-/-Ccng2-/- mice had lower body weight (Figure 1A). Also, knocking out of the Ccng2 gene in Apoe-/- mice resulted in lower levels of serum total cholesterol (TC) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), while the triglyceride (TG) level of the two groups showed no significant difference (Figure 1B,C). Results from the Oil red O staining showed that the plaque area of Apoe-/-Ccng2-/- mice was significantly reduced compared to Apoe-/- mice, indicating that Ccng2 knockout alleviated atherosclerosis in Apoe-/- mice (Figure 1D,E). The atherosclerotic plaque area and aortic root lumen cross-sectional area were used to assess the degree of atherosclerosis in two groups. The results showed that Apoe-/-Ccng2-/- mice had reduced atherosclerotic plaque area compared to Apoe-/- mice (Figure 1F,G). The results from H&E staining were consistent with the Oil Red O staining (Figure 1H,I).

Ccng2 knockout reduced VSMCs-derived foam cell formation and expression of p-NF-κB/LOX-1 in Apoe-/- mice

To further analyze the mechanism of the Ccng2 gene associated attenuation of atherosclerosis and foam cell formation; we performed immunohistochemistry experiments and examined the expressions of VSMCs marker α-SMA and macrophage marker CD68 in the aortic plaques. We found that Apoe-/-Ccng2-/- mice exhibited decreased expression of α-SMA in aortic plaques compared to the Apoe-/- mice, while the CD68 expression did not change (Figure 2A,B,C,D). This indicates that the effect of Ccng2 knockout on form cells was mainly derived from VSMCs. The immunohistochemical analysis revealed that Apoe-/-Ccng2-/- mice, having reduced atherosclerotic plaque area compared to Apoe-/- mice (Figure 1), also had decreased levels of p-NF-κB and LOX-1 (Figure 2E,F,G,H). This suggests that Ccng2 knockdown inhibited the activation of NF-κB and downregulated LOX-1 attenuating the formation of atherosclerotic plaques.

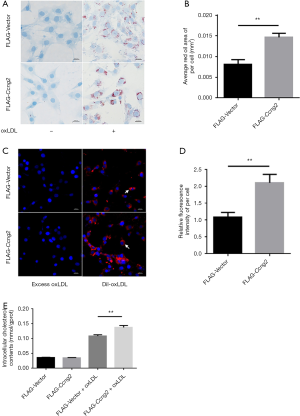

Over-expression of cyclin G2 promoted uptake and accumulation of lipids in MOVAS cells

Previous studies demonstrated that stimulation with 80 µg/mL ox-LDL for 24 hours leads to foam cell formation of MOVAS cells. Accordingly, as shown in Figure 3A,B, MOVAS cells transfected with FLAG-Ccng2 plasmid, over-expressing cyclin G2, showed increased intracellular lipid droplet content compared to the control FLAG-Vector group. This indicated that cyclin G2 indeed promotes the lipid accumulation in VSMCs to induce foam cell formation. Moreover, MOVAS cells overexpressing cyclin G2 also showed significantly enhanced uptake of fluorescently labeled Dil-oxLDL (Figure 3C,D). Using the enzymatic method for cellular TC analysis, we found that in the absence of the ox-LDL, TC content between the FLAG-Vector and FLAG-Ccng2 groups was similar. However, upon ox-LDL intervention, the TC content in both the FLAG-Vector + oxLDL and FLAG-Ccng2+oxLDL groups increased significantly. Interestingly, between the two groups, the TC content in the FLAG-Ccng2+oxLDL group was relatively higher than that of the FLAG-Vector + oxLDL group (Figure 3E). This again indicates that cyclin G2 up-regulated the cholesterol content in VSMCs-derived foam cells.

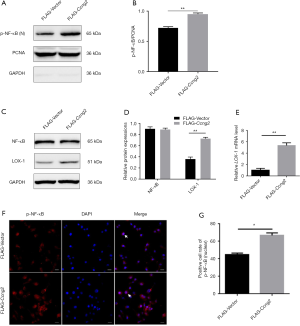

Over-expression of cyclin G2 up-regulated the expressions of LOX-1 and nuclear p-NF-κB in MOVAS cells

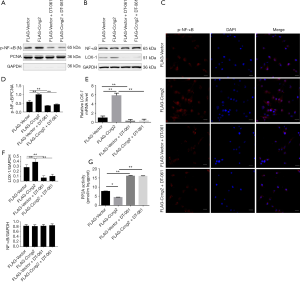

Upon ox-LDL induced stimulation of foam cell formation in the FLAG-Ccng2 and FLAG-Vector groups of cells, the nuclear protein fraction from both the groups was extracted to analyze p-NF-κB expression. We found that p-NF-κB expression in the FLAG-Ccng2 group was higher than the FLAG-Vector group (Figure 4), while the total NF-κB expression between the two groups showed no significant difference (Figure 4C,D). These results were further verified by immunofluorescence staining. Notably, the fluorescence intensity in the FLAG-Ccng2 group was higher, suggesting enhanced expression of p-NF-κB in the nucleus (Figure 4F). The quantitative statistical analysis also showed that the percentage of p-NF-κB positive cells in the FLAG-Ccng2 group was higher (Figure 4G), indicating that cyclin G2 promoted NF-κB phosphorylation and nuclear translocation. Additionally, LOX-1, both at mRNA and protein levels, was markedly upregulated in the FLAG-Ccng2 group than the FLAG-Vector group (Figure 4C,D,E). Overall, these results demonstrated that cyclin G2 promoted the expression of p-NF-κB and LOX-1 during oxLDL-induced foaming of VSMCs.

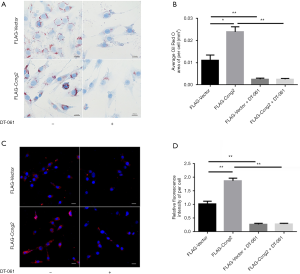

Cyclin G2 regulated the uptake and accumulation of lipids in MOVAS cells via inhibiting the enzymatic activity of PP2A

We found that after activation of PP2A, the intracellular lipid accumulation was markedly reduced in both the FLAG-Vector group and FLAG-Ccng2 group. This indicated that the effect of cyclin G2 on lipid intake was through regulating the activity of PP2A (Figure 5A,B). Moreover, DT-061 intervention significantly reduced the uptake of fluorescently labeled Dil-oxLDL in both groups (Figure 5C,D). These results indicated that lipid endocytosis promoting effects of cyclin G2 could be eliminated using PP2A agonists.

Activation of PP2A reversed the effects of cyclin G2 on foam cell formation via suppressing the p-NF-κB/LOX-1 pathway

As shown in Figure 6 the nuclear expression of p-NF-κB was markedly enhanced by over-expression of cyclin G2, while DT-061 intervention suppressed p-NF-κB levels. Furthermore, the immunofluorescence study showed that DT-061 intervention significantly lowered the percentage of p-NF-κB positive cells in the FLAG-Ccng2 group (Figure 6C). This indicated that cyclin G2 promoted NF-κB phosphorylation and nuclear translocation by inhibiting PP2A. Also, DT-061 intervention could reverse the cyclin G2 mediated upregulation of LOX-1 (Figure 6B,E,F). Furthermore, results presented that demonstrated the the PP2A activity was decreased by the over-expression of cyclin G2, which was abrogated by DT-061 (Figure 6G). Overall, these results suggested that cyclin G2 promotes the formation of foam cells in atherosclerosis via the PP2A/NF-κB/LOX-1 pathway.

Discussion

Knowing the cell type involved in the development of atherosclerosis is vital information in elucidating the mechanism of the disease (19). Previously, it was believed that foam cells in atherosclerotic plaques were mainly derived from macrophages. However, based on lineage tracing technology, several recent studies suggest that foam cells derived from VSMCs play a critical role in atherosclerotic plaques formation (20,21). Under normal physiological conditions, differentiated VSMCs express contractile proteins such as α-SMA and smooth muscle myosin heavy chain (SMMHC). Both of these are known markers of mature and differentiated VSMCs. In an event of vascular endothelial injury, inflammation is activated and these markers are inhibited. This triggers a synthetic phenotype in VSMCs and transforms them into foam cells (22,23). Interestingly, the cellular expression of macrophage marker CD68 also gets upregulated during the event (24,25).

Cyclin G2, a member of the cyclin G family, is a potential tumor suppressor (26). Interestingly, cyclin G2 also functions as a co-activator of PPARγ to promote differentiation and maturation of preadipocytes (7). Recently it was reported that upregulation of DNA methyltransferase 3a (Dnmt3a1), which inhibits fat formation during the early adipocyte differentiation, significantly up-regulated cyclin G2 but downregulated PPAR-γ (27). Moreover, the bodyweight of the Dnmt3a1 overexpressing mice, also on a high-fat diet, did not change. However, the inflammatory response was markedly increased which could be due to the overexpression of cyclin G2 in these mice (28). Since the inflammatory response is closely associated with atherosclerosis (29), cyclin G2 could also affect the progression of atherosclerosis. However, the role of cyclin G2 in atherosclerosis is not clear. Therefore, to investigate the role of cyclin G2 in the development of atherosclerotic lesions, we first constructed Apoe-/-Ccng2-/- mice and successfully established the atherosclerosis mice model. We found that Apoe-/-Ccng2-/- mice had fewer lipid plaques than Apoe-/- mice. Moreover, using immunohistochemistry experiments, we found that the expression of VCMCs marker α-SMA was higher in Apoe-/- mice than that of Apoe-/-Ccng2-/- mice. This indicated that foam cells were mainly derived from VSMCs, which is otherwise inhibited by cyclin G2.

Other than SRA and CD36, LOX-1 is the key scavenger receptor that is expressed on VSMCs. It is known to play an important role in the progression of atherosclerosis (30). The soluble LOX-1 (sLOX-1) can be detected in peripheral blood and therefore used as a diagnostic marker in brain and heart vascular diseases (31). Several studies found that LOX-1 levels get elevated in patients with hypertension, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and coronary heart disease (32). The ox-LDL along with LOX-1 activates NF-κB upregulating cytokines such as vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and monocyte chemokine protein 1 (MCP-1) (33). These pro-inflammatory molecules further increase LOX-1 expression in endothelial cells, leading to a vicious cycle of inflammatory response mediated by ox-LDL, LOX-1, and NF-κB (34). Additionally, other proinflammatory and atherosclerotic factors such as interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and TNF-α upregulate LOX-1 in VSMCs (35). Furthermore, activation of LOX-1 exacerbates oxidative stress, leading to the formation of more ox-LDL which additionally intensifies the overall effect (36).

In our animal experiments, we found that Ccng2 knockout mice had reduced atherosclerotic plaque, indicating that cyclin G2 promoted atherosclerosis. Subsequent in vitro experiments suggested that cyclin G2 promoted VSMCs foaming by up-regulating scavenger receptor LOX-1, and NF-κB signaling pathway. Interestingly, PP2A, a ubiquitous phosphatase, plays an important role in the regulating NF-κB signaling pathway (37). Also, PP2A itself is regulated by cyclin G2 (38). Therefore, we speculated that cyclin G2 might regulate the NFκB signaling pathway via inhibition of PP2A activity. To verify this, we used an activator of PP2A to determine the effects. We found that with the PP2A activator, VSMCs foaming was relieved. Also, the nuclear translocation of p-NF-κB and LOX-1 levels were reduced. Therefore, in brief, we propose that cyclin G2 promotes the formation of VSMCs-derived foam cells by inhibiting the PP2A phosphatase activity, thereby activating the NF-κB signaling pathway and up-regulating the level of LOX-1. We believe that this novel information can help in developing effective treatment against atherosclerosis.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China [No. 82070794] and the Foundation of the Education Department of Liaoning Province [LZDK201703, JC2019031].

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the ARRIVE reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-6207

Data Sharing Statement: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-6207

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-6207). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The animal experiments were approved by the Ethics Review Committee of China Medical University (IACUC NO. 201903153). All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Pi H, Wang Z, Liu M, et al. SCD1 activation impedes foam cell formation by inducing lipophagy in oxLDL-treated human vascular smooth muscle cells. J Cell Mol Med 2019;23:5259-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dubland JA, Francis GA. So Much Cholesterol: the unrecognized importance of smooth muscle cells in atherosclerotic foam cell formation. Curr Opin Lipidol 2016;27:155-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zang YH, Chen D, Zhou B, et al. FNDC5 inhibits foam cell formation and monocyte adhesion in vascular smooth muscle cells via suppressing NFκB-mediated NLRP3 upregulation. Vascul Pharmacol 2019;121:106579 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Allahverdian S, Chehroudi AC, McManus BM, et al. Contribution of intimal smooth muscle cells to cholesterol accumulation and macrophage-like cells in human atherosclerosis. Circulation 2014;129:1551-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gao J, Zhao C, Liu Q, et al. Cyclin G2 suppresses Wnt/β-catenin signaling and inhibits gastric cancer cell growth and migration through Dapper1. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2018;37:317. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li S, Gao J, Zhuang X, et al. Cyclin G2 Inhibits the Warburg Effect and Tumour Progression by Suppressing LDHA Phosphorylation in Glioma. Int J Biol Sci 2019;15:544-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aguilar V, Annicotte JS, Escote X, et al. Cyclin G2 regulates adipogenesis through PPAR gamma coactivation. Endocrinology 2010;151:5247-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gao J, Liu Q, Liu X, et al. Cyclin G2 suppresses estrogen-mediated osteogenesis through inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. PLoS One 2014;9:e89884 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Poirier P, Giles TD, Bray GA, et al. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: pathophysiology, evaluation, and effect of weight loss: an update of the 1997 American Heart Association Scientific Statement on Obesity and Heart Disease from the Obesity Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Circulation 2006;113:898-918. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Veronese N, Stubbs B, Crepaldi G, et al. Relationship Between Low Bone Mineral Density and Fractures With Incident Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Bone Miner Res 2017;32:1126-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Minta J, Jungwon Yun J, St Bernard R. Microarray analysis of ox-LDL (oxidized low-density lipoprotein)-regulated genes in human coronary artery smooth muscle cells. Cell Biol Int Rep (2010) 2010;17:e00007.

- Manning-Tobin JJ, Moore KJ, Seimon TA, et al. Loss of SR-A and CD36 activity reduces atherosclerotic lesion complexity without abrogating foam cell formation in hyperlipidemic mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2009;29:19-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kattoor AJ, Kanuri SH, Mehta JL. Role of Ox-LDL and LOX-1 in Atherogenesis. Curr Med Chem 2019;26:1693-700. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Harman JL, Jørgensen HF. The role of smooth muscle cells in plaque stability: Therapeutic targeting potential. Br J Pharmacol 2019;176:3741-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen Z, Pan X, Sheng Z, et al. Baicalin Suppresses the Proliferation and Migration of Ox-LDL-VSMCs in Atherosclerosis through Upregulating miR-126-5p. Biol Pharm Bull 2019;42:1517-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Han X, Li B, Ye X, et al. Dopamine D(2) receptor signalling controls inflammation in acute pancreatitis via a PP2A-dependent Akt/NF-κB signalling pathway. Br J Pharmacol 2017;174:4751-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen B, Li J, Zhu H. AMP-activated protein kinase attenuates oxLDL uptake in macrophages through PP2A/NF-κB/LOX-1 pathway. Vascul Pharmacol 2016;85:1-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang Y, Goulart RA, Pantanowitz L. Oil red O staining in cytopathology. Diagn Cytopathol 2011;39:272-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Basatemur GL, Jørgensen HF, Clarke MCH, et al. Vascular smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol 2019;16:727-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dobnikar L, Taylor AL, Chappell J, et al. Disease-relevant transcriptional signatures identified in individual smooth muscle cells from healthy mouse vessels. Nat Commun 2018;9:4567. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chistiakov DA, Melnichenko AA, Myasoedova VA, et al. Mechanisms of foam cell formation in atherosclerosis. J Mol Med (Berl) 2017;95:1153-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Feil S, Fehrenbacher B, Lukowski R, et al. Transdifferentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells to macrophage-like cells during atherogenesis. Circ Res 2014;115:662-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jacobsen K, Lund MB, Shim J, et al. Diverse cellular architecture of atherosclerotic plaque derives from clonal expansion of a few medial SMCs. JCI Insight 2017;2:e95890 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Albarrán-Juárez J, Kaur H, Grimm M, et al. Lineage tracing of cells involved in atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2016;251:445-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vengrenyuk Y, Nishi H, Long X, et al. Cholesterol loading reprograms the microRNA-143/145-myocardin axis to convert aortic smooth muscle cells to a dysfunctional macrophage-like phenotype. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2015;35:535-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhao C, Gao J, Li S, et al. Cyclin G2 Suppresses Glomerulosclerosis by Regulating Canonical Wnt Signalling. Biomed Res Int 2018;2018:6938482 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abdalla BA, Li Z, Ouyang H, et al. A Novel Dnmt3a1 Transcript Inhibits Adipogenesis. Front Physiol 2018;9:1270. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kamei Y, Suganami T, Ehara T, et al. Increased expression of DNA methyltransferase 3a in obese adipose tissue: studies with transgenic mice. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:314-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Soeki T, Sata M. Inflammatory Biomarkers and Atherosclerosis. Int Heart J 2016;57:134-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pirillo A, Norata GD, Catapano AL. LOX-1, OxLDL, and atherosclerosis. Mediators Inflamm 2013;2013:152786 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tuten A, Aydemir B, Oncul M, et al. The association of lectin-like oxidized LDL receptor 1 (LOX-1) K167N and 3'UTR188CT polymorphisms with maternal plasma soluble LOX-1 levels and preeclampsia risk in Turkish population. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2015;291:563-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yin YW, Liao SQ, Zhang MJ, et al. TLR4-mediated inflammation promotes foam cell formation of vascular smooth muscle cell by upregulating ACAT1 expression. Cell Death Dis 2014;5:e1574 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Qian W, Cai X, Qian Q, et al. Astragaloside IV protects endothelial progenitor cells from the damage of ox-LDL via the LOX-1/NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. Drug Des Devel Ther 2019;13:2579-89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ge X, Zhang DM, Li MM, et al. Microglial LOX-1/MAPKs/NF-κB positive loop promotes the vicious cycle of neuroinflammation and neural injury. Int Immunopharmacol 2019;70:187-200. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lubrano V, Balzan S. Roles of LOX-1 in microvascular dysfunction. Microvasc Res 2016;105:132-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xu S, Ogura S, Chen J, et al. LOX-1 in atherosclerosis: biological functions and pharmacological modifiers. Cell Mol Life Sci 2013;70:2859-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tsuchiya Y, Osaki K, Kanamoto M, et al. Distinct B subunits of PP2A regulate the NF-κB signalling pathway through dephosphorylation of IKKβ, IκBα and RelA. FEBS Lett 2017;591:4083-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arachchige Don AS, Dallapiazza RF, Bennin DA, et al. Cyclin G2 is a centrosome-associated nucleocytoplasmic shuttling protein that influences microtubule stability and induces a p53-dependent cell cycle arrest. Exp Cell Res 2006;312:4181-204. [Crossref] [PubMed]