Extended leukocyte differential count and C-reactive protein in septic patients with liver impairment: diagnostic approach to evaluate sepsis in intensive care unit

Introduction

Despite recent advances in diagnosis and treatment both of sepsis and septic shock (SS), these conditions remain the major cause of death in intensive care units (ICUs) around the globe. Recent data confirm that the overall mortality rate of systemic infections can be as high as 28.6% in the US, with a trend exhibiting a constant increase (1-3). Early diagnosis of sepsis still remains challenging, even when using the criteria of the International Sepsis Definitions Conference (4).

The current biomarkers for diagnosis of sepsis include procalcitonin, C-reactive protein (CRP), lactic acid, immature granulocytes (IG), and delta neutrophil (NE) index (5-11). Sepsis is usually described as a 2-step process, involving an early phase defined by the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, and a later one, characterized by the release of anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (3). Such a biphasic nature is impaired in patients with liver cirrhosis (3,12). Sepsis in patients with liver impairment is indeed accompanied by a markedly imbalanced cytokine response, wherein paraphysiological responses, that are normally beneficial for counteracting infections, may turn into a disproportionate, detrimental inflammation (12). The measurement of many cytokines is usually expensive, often unavailable in many middle-size clinical laboratories (13,14), whereas leukocytes (WBC) morphological and functional evaluation can be regarded as more affordable and practical strategy for monitoring the inflammatory response in sepsis, as well as for providing rapid and reliable biological information in the follow-up of both cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic patients (15).

Several technical improvements characterize the novel generation of hemocytometers, which provide nontraditional parameters along with the traditional complete blood count (CBC), including the IG count, expressed as absolute (#) and percentage (%) value (16,17), or the highly fluorescent cells (HFLC) count (18,19). The new Sysmex XN-9000 analyzer (Sysmex Co., Kobe, Japan) generates an extended leukocyte differential count including many adjunctive parameters. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the clinical significance of some of these new and non-traditional parameters (i.e., IG, HFLC) along with CRP for the early diagnosis and monitoring of sepsis patients in the ICU, with special focus on patients with liver impairment.

Materials and methods

Subject population

The study population consisted in 115 adult patients admitted to the ICU of the General Hospital of Bergamo, Italy, between February and March 2015. The only inclusion criteria were age ≥18 years, whereas all patients with positive history for hematologic disorders and/or hospitalized for less than 48 h were excluded.

Clinical data including sign and sites of concomitant infection (documented or suspected) and presence/absence of liver disease classified according to Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score (20) were recorded at ICU admission. In the days following ICU admission, patients underwent regular testing including a large panel of blood tests as well as two daily clinical reassessments until discharge from ICU. More specifically, the thoughtful clinical assessment included information about presence/absence of sepsis using the International Sepsis Definitions Conference guidelines (4), as well as the degrees of severity by calculation of the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score (21).

All patients admitted in ICU were then classified in three classes, as follows: no sepsis (NS), sepsis (SE) and SS. Each patient was also evaluated for the presence/absence of liver impairment. Accordingly, six groups were finally obtained, as follows: no hepatic disease and no sepsis (NHNS), no hepatic disease and sepsis (NHSE), no hepatic disease and septic shock (NHSS), hepatic disease and no sepsis (HNS), hepatic disease and sepsis (HSE), hepatic disease and septic shock (HSS).

The study also included 200 healthy subjects (HS), selected from healthy blood donors (100 men and 100 women) with age between 18-70 years (average: 43.0 years; 95% CI, 41.0-45.0 years). Inclusion criteria were the same as for ICU patients, including negative anamnesis and normal serum levels of creatinine, glucose, liver enzymes, CRP and ferritin.

Samples preparation and methods

A total number of 1,022 peripheral whole blood samples (200 HSs and 822 ICU’s patients) collected in K3EDTA blood tubes (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and processed on XN-9000 (Sysmex Co., Kobe, Japan) were analyzed. CBC and extended leukocyte differential count was always performed within 2 h from sample collection.

The main parameters evaluated included total count and leukocyte differential count [NE, lymphocytes (LY), monocytes (MO), eosinophils (EO), basophils (BASO), IG and HFLC] in absolute (#) values.

The imprecision of leukocyte count, their standard differential count and IG parameters were also assessed according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) EP5-A3E guideline (22), by analyzing three different levels (1, 2 and 3) of control material (XN-CHECK; Streck Laboratories Inc., Omaha, NE, USA) in duplicate for 40 consecutive working days.

The concentration of CRP was also measured on serum samples, using an immunoturbidimetric assay on ADVIA 2400 (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics USA). The total imprecision of this assay was <3.4%, as quoted by the manufacturer.

Statistical analysis

The distribution of values was assessed with Shapiro-Wilk test. The preliminary analysis of data revealed a non-normal distribution of data, so that results were reported as median for each class of subjects. The statistical differences were then evaluated with the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis and Steel-Dwass-Critchlow-Fligner (pair comparison) tests. The diagnostic accuracy of all parameters was compared with the criteria defined by the International Sepsis Definitions Conference (4) by means of receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves. The statistical analysis was performed with Analyse-it (Analyse-it Software Ltd, Leeds, UK). The study was carried out in accord with the Declaration of Helsinki, and under the terms of all relevant local legislation. The investigation was based on pre-existing samples, so that ethical permission and informed consent were unnecessary.

Results

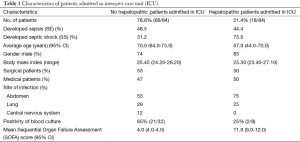

Eighty-four patients were enrolled in this study on 115 patients admitted in ICU (Table 1) shows the characteristics of population studied: 44 subjects (52%) with NS, 40 (48%) with sepsis or severe sepsis. In the last group, 20 patients (50%) had sepsis at ICU, whereas 16 (40%) developed SS during ICU stay.

Full table

Leukocyte differential counts and CRP

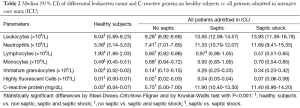

The median value of leukocytes and of their differential count (NE, LY, MO, EO, BASO, IG and HFLC) and CRP in all subjects (84 patients admitted to ICU and 200 HSs) were shown in Table 2.

Full table

The median value of all leukocyte differential counts and CRP of the HSs group were significantly different in the three classes of NS, SE and SS patients. The leukocyte, NE, IG, HFLC counts and the values of CRP were significantly increased in SE and SS patients compared to the NS group.

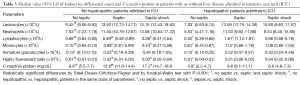

Table 3 shows the median values of leukocytes, their differential counts and CRP in the six groups of patients: NHNS, NHSE, NHSS, HNS, HSE, and HSS. The median values for all parameters except IG and HFLC were found to be significantly higher than in NHNS patients compared to the HNS patients.

Full table

The median LY value in NHSS patients was significantly lower than in those with NHNS and NHSE. In patients with liver impairment, LY did not show a definite trend, with the median value significantly increased in the HSE group vs. patients with HNS and HSS. Notably, the median values of LY in patients with no liver disease were always significantly different from those of hepatopathic patients

The median value of MO was significantly lower in NHSS patients than in the NHNS and NHSE groups (Table 3). Conversely, the MO values exhibited a progressive increasing trend, wherein in both patients with HSE and HSS they were found to be significantly higher about double compared to the HNS group. Finally, the median value of CRP was found to be increased in NHSE and NHSS patients compare to the NHNS, HSE and HSS group (Table 3).

EO and BASO median values do not show any significant difference (data not shown).

Leukocyte differential count, CRP and diagnostic performance

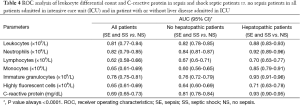

The ROC analysis performed on leukocyte, NE and IG (Table 4) shows different diagnostic performances, with AUCs ranging from 0.78 (95% CI, 0.75-0.81; P<0.001) for IG in all patients admitted to ICU, to 0.93 (95% CI, 0.83-0.93) in the group of patients with liver disease (Table 4).

Full table

The ROC curve analysis calculated for LY and MO reveals poor diagnostic performance, as shown in Table 4, with the exception of the MO count in hepatopathic patients, exhibiting an AUC of 0.85 (95% CI, 0.79-0.91; P<0.0001). As regards CRP, the AUC for all patients admitted to ICU was characterized by a poor diagnostic performance (i.e., 0.69; 95% CI, 0.65-0.73). Interestingly, a much higher AUC value was found when patients were classified as having or not liver impairment, with AUC values increasing to 0.81 (95% CI, 0.78-0.84; P<0.001) and 0.93 (95% CI, 0.90-0.95; P<0.001), respectively (Table 4).

The AUCs of EO and BASO do not show significant diagnostic performances, with values always below 0.65 (data not shown).

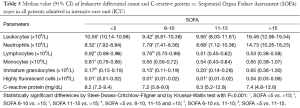

Leukocyte differential count and CRP vs. SOFA score

The correlation between the median values of leukocyte differential count, CRP and the SOFA score for all ICU patients is shown in Table 5. The median values of leukocytes, NE, IG and HFLC in all ICU patients increased in parallel with the SOFA score. Notably, the median value of IG in patients with SOFA score <5 was 0.17×109/L (95% CI, 0.15-0.19), increasing to 0.65×109/L (95% CI, 0.36-1.30) in those with SOFA score >15.

Full table

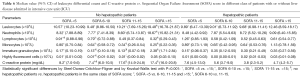

A similar analysis obtained after dividing patients according to the presence of liver disease, is shown in Table 6.

Full table

In the group of patients without liver impairment and with SOFA score >15 are shown values always significantly higher respect to patients with liver impairment (Table 6).

On the contrary MO median values decrease in parallel with the SOFA score only in the patients without liver impairment. Notably, the MO median value in patients without liver impairment are significant different respect to hepatopathic patients in the two classes of patients with the SOFA score >10 (Table 6).

CRP shows a growing trend respect of SOFA score in the patients without liver disease, whereas the patients with liver disease does not show any significant difference between the median values across all the SOFA score grades.

EO and BASO median values do not show any significant correlation with the SOFA score (data not shown).

Discussion

A timely diagnosis and an appropriate management of patients with sepsis remain important challenges. Therefore, the availability of easy and inexpensive parameters such as those generated by many modern hematological analyzers should be regarded as a valuable perspective. The possible presence of liver disease or failure is an additional problem for patient management, wherein a number of diagnostic parameters may exhibit substantial variations in patient with liver impairment.

Taken together, the results of our study show that all classes of ICU patients display significantly different values of various traditional and non-traditional parameters available with the XN-9000 hematological analyzer (Table 2). Another important evidence emerged from this study, is that the presence of liver disease in ICU patients is associated with remarkable differences in values of leukocyte differential count and CRP. One exception to this rule is represented by leukocytes, NE, IG and HFLC, wherein their values were found to be progressively increased according to the severity of the infection (Tables 2,3). Overall, these findings are in agreement with data available from the literature (23,24). As regards leukocytes, NE and IG, these parameters exhibit a good agreement with the SOFA scores (Tables 5,6).

Interestingly, the values of LY and MO exhibited an independent and peculiar trend between subjects with or without liver disease (Tables 2,3) and the diagnostic performance were hence rather different depending on the presence of hepatopathy (Table 4).

LY and MO, in the two classes of patients, show also a peculiar trend according to the SOFA classification, regardless of the presence/absence of sepsis (Table 6).

All this evidence can be attributed to the presence of a different inflammatory response in septic patients with liver impairment, as previously described (3).

The results of the correlations between hematological parameters and the SOFA score are also noteworthy, suggesting that it may be advisable to interpret such values according to liver function in order to increase their diagnostic efficiency. A similar consideration applies to the interpretation of CRP values, as attested by the greater diagnostic efficiency of this biomarker in ICU patients without liver disease.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the diagnostic approach to patients with sepsis may be improved by assessing some traditional and non-traditional hematological parameters, generated by modern hemocytometers such as XN-9000. This may be relevant in septic patients with liver disease, because which other conventional biomarkers (i.e., cytokines) they display a much lower diagnostic efficiency.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Nguyen HB, Rivers EP, Abrahamian FM, et al. Severe sepsis and septic shock: review of the literature and emergency department management guidelines. Ann Emerg Med 2006;48:28-54. [PubMed]

- Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, et al. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1546-54. [PubMed]

- Angus DC, van der Poll T. Severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med 2013;369:840-51. [PubMed]

- Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, et al. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit Care Med 2003;31:1250-6. [PubMed]

- Müller B, Becker KL, Schächinger H, et al. Calcitonin precursors are reliable markers of sepsis in a medical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2000;28:977-83. [PubMed]

- Harbarth S, Holeckova K, Froidevaux C, et al. Diagnostic value of procalcitonin, interleukin-6, and interleukin-8 in critically ill patients admitted with suspected sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164:396-402. [PubMed]

- Reinhart K, Bauer M, Riedemann NC, et al. New approaches to sepsis: molecular diagnostics and biomarkers. Clin Microbiol Rev 2012;25:609-34. [PubMed]

- Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest 1992;101:1644-55. [PubMed]

- Park BH, Kang YA, Park MS, et al. Delta neutrophil index as an early marker of disease severity in critically ill patients with sepsis. BMC Infect Dis 2011;11:299. [PubMed]

- Seok Y, Choi JR, Kim J, et al. Delta neutrophil index: a promising diagnostic and prognostic marker for sepsis. Shock 2012;37:242-6. [PubMed]

- Nahm CH, Choi JW, Lee J. Delta neutrophil index in automated immature granulocyte counts for assessing disease severity of patients with sepsis. Ann Clin Lab Sci 2008;38:241-6. [PubMed]

- Gustot T, Durand F, Lebrec D, et al. Severe sepsis in cirrhosis. Hepatology 2009;50:2022-33. [PubMed]

- Faix JD. Biomarkers of sepsis. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 2013;50:23-36. [PubMed]

- Bloos F, Reinhart K. Rapid diagnosis of sepsis. Virulence 2014;5:154-60. [PubMed]

- Chongliang F, Yuzhong L, Qian S, et al. Development of a prognostic score using the complete blood cell count for survival prediction in unselected critically ill patients. Biomed Res Int 2013;2013:105319.

- Maenhout TM, Marcelis L. Immature granulocyte count in peripheral blood by the Sysmex haematology XN series compared to microscopic differentiation. J Clin Pathol 2014;67:648-50. [PubMed]

- Briggs C, Longair I, Kumar P, et al. Performance evaluation of the Sysmex haematology XN modular system. J Clin Pathol 2012;65:1024-30. [PubMed]

- Arneth BM, Ragaller M, Hommel K, et al. Novel parameters of extended complete blood cell count under fluorescence flow cytometry in patients with sepsis. J Clin Lab Anal 2014;28:130-5. [PubMed]

- van Mirre E, Vrielink GJ. Sensitivity and specificity of the high fluorescent lymphocyte count-gate on the Sysmex XE-5000 hematology analyzer for detection of peripheral plasma cells. Clin Chem Lab Med 2011;49:685-8. [PubMed]

- Kamath PS, Wiesner RH, Malinchoc M, et al. A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology 2001;33:464-70. [PubMed]

- Minne L, Abu-Hanna A, de Jonge E. Evaluation of SOFA-based models for predicting mortality in the ICU: A systematic review. Crit Care 2008;12:R161. [PubMed]

- CLSI. Evaluation of Precision of Quantitative Measurement Procedures; Approved Guideline, third edition. CLSI document EP05-A3. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2014.

- Ansari-Lari MA, Kickler TS, Borowitz MJ. Immature granulocyte measurement using the Sysmex XE-2100. Relationship to infection and sepsis. Am J Clin Pathol 2003;120:795-9. [PubMed]

- Park SH, Park CJ, Lee BR, et al. Sepsis affects most routine and cell population data (CPD) obtained using the Sysmex XN-2000 blood cell analyzer: neutrophil-related CPD NE-SFL and NE-WY provide useful information for detecting sepsis. Int J Lab Hematol 2015;37:190-8. [PubMed]