Factors affecting decision-making of patients choosing acupuncture in a public hospital

Introduction

Acupuncture is a subset of the practice of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), which has been practiced for more than 4,000 years. Based on the holistic regulation and balance of the flow of energy within an individual’s body, it was first described in 200 BC (1). Since then, both the theory and practice of acupuncture has continued to evolve based on increasing clinical experience, research, and the development and application of new materials and technologies. Today, acupuncture has been proven to be both safe (2,3) and cost-effective (4-6). In 2003, a scientific report by the World Health Organisation (WHO), studying controlled clinical trials, identified 28 diseases and conditions for which acupuncture was effective for (7). Apart from treating pain (8), acupuncture has been used in the management a wide variety of conditions including asthma (9), dermatitis (10), cancer (11), polycystic ovary syndrome (12) and insomnia (13,14) via evidence-based techniques (15).

A global survey by WHO in 2012 revealed that out of 129 member states which responded to the survey, 103 acknowledged its practice within its state, 29 acknowledged the official implementation of regulations for acupuncture providers and 18 declared health insurance coverage for acupuncture (16). Acupuncture spread to Korea and Japan in the 6th century AD. Europe, Australia and North America were introduced to it in the 16th to 19th centuries AD (17,18).

Since the spread of TCM to various countries, the extent of practice of acupuncture has varied across the board. In Switzerland, for instance, acupuncture is one of many forms of complementary therapies which include anthroposophical medicine, homeopathy and neural therapy (19,20). In the United Kingdom (UK), acupuncture has been made available within the National Health Service (NHS) through physiotherapists, pain clinics and primary care clinics (21,22). In Tehran, the frequency of complementary medicine and acupuncture usage was approximately 0.4% (23). However, in Australia, almost 1 in 10 Australians have received acupuncture treatment either within state-run or private centres (24). In the United States (US), acupuncture usage is higher, ranging from 15.1% to 34% (25,26). Regardless of the extent of utilisation of acupuncture within populations and their perceived benefits within healthcare systems, studies have shown that there is a growing inclination of people toward complementary medicine in general (27,28).

In recent years, acupuncture has been increasingly introduced within public hospitals. The Royal London Hospital for Integrated Medicine, the largest hospital in England offering complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), provides acupuncture services. It was integrated as part of The University College London Hospitals in 2002 (29). Jacobsen et al. (30) revealed that 63.2% of public Norwegian hospitals included in their study offered CAM, with 37.3% of all hospitals offering acupuncture. Similarly, 33.7% of public hospitals in Denmark offer CAM, with the majority of them offering acupuncture services (31). Another study performed in the French-speaking part of Switzerland revealed that 15 out of 25 public hospitals which participated in the study offered CAM, with the most common CAM service being acupuncture (32).

Thus far, there have been no studies looking at the factors which influence the decision making process of patients in their selection of acupuncture services within public hospitals. The objective of this study is hence to understand such factors affecting the decision making process of patients when they choose to attend the acupuncture clinic in a public hospital. It is hoped that information garnered and synthesised can also be used to influence the way acupuncture is practiced within public hospitals.

Methods

A qualitative study on 14 patients who attended the acupuncture clinic at the Department of Complementary & Integrative Medicine, Tan Tock Seng Hospital was conducted. Ethics approval was obtained on 27th June 2013 via the institution’s domain-specific ethics board [Domain Specific Review Board (DSRB)] (DSRB Reference: 2013/00301). Patients were identified via convenience sampling based on their availability before or after their appointment with the acupuncturist. All participants were regular patients at the acupuncture clinic. All participants were invited to participate in the study face-to-face. Three potential participants refused to participate due to insufficient time on their part to be able to commit to the study. All 14 interviews were conducted individually and were digitally audio recorded at the Complementary & Integrative Medicine Clinic in Tan Tock Seng Hospital with signed informed consent before the entire interview proper. The consent taken allows investigators to interview participants, analyse data from the interview, and publish any relevant findings.

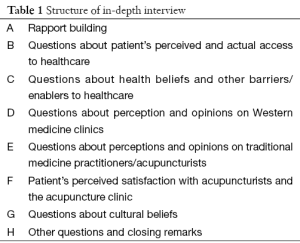

The interviews were performed via a one-off semi-structured interview style using the phenomenological methodology by two investigators (AAS and KTHB). Both interviewers are students from the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine. AAS was trained by the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health in qualitative interviewing and has had experience in interviewing in previous qualitative studies. He trained KTHB in qualitative interviewing and coordinated their interviewing methodology to keep the questioning style consistent. An interview guide was designed to keep interviews as consistent as possible, with potential to digress when necessary based on themes brought up by participants. The interview guide was designed to identify participants’ knowledge, attitudes and beliefs regarding acupuncture, as well as perceived and actual barriers and enablers to healthcare, based on their experiences in both Western medicine and acupuncture clinics (Table 1, Supplementary).

Full table

Field notes were penned down during the interviews. These notes supplemented the recorded interviews. Interviews conducted took between 20 to 45 min. All recorded interviews were transcribed at verbatim, data coded and analysed by two investigators (AAS and KTHB). Coding of the analysed transcripts resulted in the emergence of major themes regarding knowledge, attitudes and beliefs, as well as barriers and enablers to the usage of acupuncture. These themes were further studied, via framework analysis, to understand the decision making process of patients who attend the acupuncture clinic.

Results

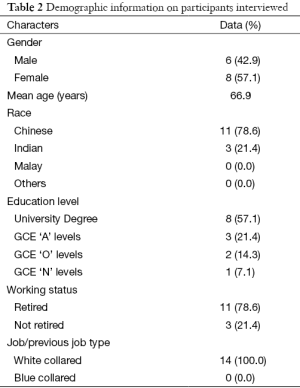

A total of 14 participants were recruited from the acupuncture clinic in order to obtain a sufficiently broad range of perspectives regarding the various factors which influence decision making when patients select to attend the acupuncture clinic for the management of their medical conditions. All participants interviewed had attended the acupuncture clinic in Tan Tock Seng Hospital more than one time. Simple demographic information of the patients can be found in Table 2.

Full table

The factors discussed can be classified into four main groups in relation to their influence on decision making of patients—namely, factors affecting the level and value of patient-centric care, the confidence and trust patients have with regard to acupuncture services provided relative to Western medicine, the presence of collaborative efforts between acupuncturists and Western medicine practitioners, and the type of knowledge, culture and beliefs society has regarding the role of acupuncture and Western medicine. The four factor groups have been summarised diagrammatically in Figure 1.

Level and value of patient-centric care

Factors contributing to actual and perceived patient-centric care are a core classification of factors which affect the way patients decide upon utilising acupuncture for their diseases and illnesses. Many patients stated that one of the main reasons they decided to seek acupuncture services was because of the long waiting queues and little time doctors spent with them in the Western medicine clinics. Many a times, after a consult with the Western medicine doctor, they may even have many questions unanswered. This, however, was not the case in the clinic which we conducted the interviews in. The acupuncture clinic was described by participants as being patient-centric based on the shorter waiting times, increased time spent with the acupuncturists, and acupuncturists appropriately handling the concerns of patients. To many participants, the patient-centricity of the clinic was generally translated to the perception that acupuncturists cared highly for their patients and placed more effort in the management of each and every patient.

“He will always ask if there are any other questions or anything else I would like to share with him. I feel that he does not really bother about time. If I suddenly have pain in the arm, he will help me massage it. He is very patient-centred.”—Patient 6.

“…the acupuncturist is quite flexible. Even if I would like to arrange an appointment with the acupuncturist next week at this moment, Mr N will say that it is possible. For instance if next week there is no slot, he told me, ‘never mind, it doesn’t matter. I will just tell the people’. Because in between seeing his scheduled patients, he is willing to see us.”—Patient 8.

Confidence and trust amongst patients

Factors affecting the level of confidence and trust amongst patients were addressed both in the context of comparing acupuncture with the practice of Western medicine, and comparing acupuncture clinics in public hospitals with standalone acupuncture clinics. Several participants were concerned about side effects of medications which Western medicine practitioners prescribed. They preferred to utilise acupuncture, as a form of natural therapy to their medical illnesses. Many participants also lacked confidence in the proposed surgeries by Western medicine practitioners for some of their ailments such as knee osteoarthritis. The relative confidence and trust in treatment practices of Western medicine and acupuncture was a comparison that some patients made before eventually attending the acupuncture clinic. The presence of publicised qualifications of the acupuncturists in the clinic also increased the confidence of patients toward the acupuncture clinic. Furthermore, the branding provided to the clinic being situated within the compounds of the public hospital was also mentioned by several participants as a key point in strengthening the confidence patients had in the clinic. This was unlike many standalone clinics which some patients had heard of or even attended. They had the perception that the quality of service provided by acupuncture clinics in public hospitals were generally higher than those not within the compounds of public hospitals.

“That clinic (referring to a clinic not within situated with a hospital) has quality issues. You read the newspaper and realise that it has issues. I have problems trusting such a clinic.”—Patient 3.

“I am always very apprehensive. I am always very scared. In any HDB (Housing Development Board) estate, you can find a lot of these fly by night ones (acupuncture clinics)…I am quite apprehensive of this. But because this hospital has one (acupuncture clinic), I can trust it. It has a brand name and is organised.”—Patient 5.

“I come here because of my knee. I have seen Dr K for about 3 years. He is really very good. But I’m not very sure about knee replacement. I am very apprehensive about it. I have spoken to people with it (knee replacement). They are never the same as before. I have seen some people who can’t even walk. They dance, but after knee replacement, they can walk normally but cannot dance.”—Patient 6.

Knowledge, culture and beliefs of society in the role of western medicine practitioners and acupuncturists

Thirdly, the culture present within certain groups of individuals, alongside their belief systems and knowledge contributed to their decision making pathways. Cultural influences toward decision making were especially observed amongst Chinese participants. The efficacy of traditional Chinese medicine practices, their near negligible side-effect rates, as well as their foundational principles of the balance of energy within the human body were main cultural beliefs that were brought up during the interviews. At times, these beliefs were brought up in relation to Western medicine and its inferiority as a standalone practice, without acupuncture, to effectively and efficiently manage diseases and illnesses. The beliefs itself consisted of both proper perceptions and misperceptions regarding Western medicine and acupuncture practices. These beliefs were greatly influenced by past experiences of patients with either Western medicine doctors, non-public hospital acupuncturists as well as public hospital acupuncturists both from our centre and other centres. They were also influenced by past experiences of other individuals they interact with such as family members, friends and acquaintances. The patient’s knowledge base also served as a vital foundation for belief systems to be built upon. Such knowledge foundations were classified as either sufficient, insufficient, inaccurate, or a mix of these three observed knowledge categories. Regardless, it was noted that a weak knowledge base resulted in weak belief systems filled with misperceptions. However, a strong knowledge base did not assure a belief system without misperceptions. Participants stated that they obtained their knowledge either from official sources, such as acupuncturists or even Western medicine doctors, or non-official sources, such as family members, friends and mass media. As a whole, we observed that although a large number of individuals utilised acupuncture services with appropriate knowledge and belief systems, there were some individuals who sought acupuncture without acceptable knowledge, especially in terms of accuracy, and belief systems.

“They (Western medicine practitioners) tend to give you painkillers, which I don’t believe in. I am already taking a lot of medicines. I don’t want to add on to the number of medicines I am taking. I am sure all these medicines in the long term have side effects. And I don’t want temporary measures. I don’t want painkillers which may only help me for that day. I want something which can help me longer, with minimal side effect.”—Patient 4.

“I think those who believe in acupuncture and its benefits are those Chinese educated people. They believe in this Qi and blood circulation and all these things. For the Western, the English educated ones, quite difficult to understand the benefits of acupuncture. So once you believe in it, you can see the effect better. I believe in this.”—Patient 5.

“…I feel traditional medicine is more natural. Whereas Western medicine is more chemical…”—Patient 6.

“I cannot go against the will of my family. The children play an important part. If I don’t go, they may not have faith in this. They feel western medicine is important. So just to keep them quiet, I just follow up with the English medicine doctor as well.”—Patient 8.

Collaboration between acupuncturists and western medicine practitioners

Finally, factors related to the extent of integration and collaboration between Western medicine practitioners, together with acupuncture clinics and practitioners played a role in patients eventually utilising acupuncture services. Through the interviews, we noted that many patients sought care from both Western medicine and acupuncture practitioners simultaneously, to optimise upon the advantages from each sect. For instance, some individuals continued attending their follow up appointments with their Western medicine practitioners to obtain the necessary investigations for their ailments. With such investigations, patients would plan accordingly where and who to seek treatment from. Dependent on the type and progress of disease, patients may seek treatment from acupuncture practitioners. Consequently, the integration of the acupuncture clinic within the public hospital setting has attracted many patients to the acupuncture clinic, especially in terms of convenience of location. Apart from convenience, patients viewed such integration as a step forward toward holistic care. They viewed the practice of Western medicine and acupuncture differently, noting that their foundational philosophies were not related to each other. As such, the utilisation of both services simultaneously allowed them to benefit from the strength of each practice, hence providing them the opportunity to rehabilitate faster from their ailments. Furthermore, some participants mentioned that they were referred to the acupuncture clinic, or at least provided the option of acupuncture care, by Western medicine practitioners. This indicates that such integration and collaboration between the two practices can potentially increase the confidence of patients in acupuncture services as their practices are even being recommended by Western medicine practitioners who treat patients based on unrelated philosophies.

“I will weigh between these two (acupuncturist and Western medicine practitioner), if urgent. My son is a doctor as well. So my knowledge of Western medicine has no misunderstandings. If need be, I will go to the Western doctor… I think it depends on the type of illness I am suffering from. If it is a cough and cold- at first, I will consider rest at home. Certain things such as a bad sore throat, I will see a Western doctor. Problems such as muscle pain doesn’t necessarily require consulting a Western doctor. However, if I were to stay at home, the problem will drag longer. So I will see the acupuncturist.”—Patient 5.

A major barrier to access to acupuncture services within the public hospital was the high cost of the service. Based on most of the participants’ experiences and perceptions, they believed that the cost of acupuncture services within the hospital was generally high. According to participants, this deterred many individuals from attending the clinic. For many of them, this barrier was overcome via special subsidies they were eligible to utilise due to their previous services within the government sector, such as within the education and military sectors. There were other barriers to accessing acupuncture services which were also elicited from our interviews, such as a lack of information regarding acupuncture, as well as lack of information regarding the availability of acupuncture services.

In general, amongst the four abovementioned factor groups, participants brought up at least two or more groups within their conversations. To a large extent, factors related to confidence and trust, as well as confidence, belief systems and knowledge, were brought up more often as compared to the other two groups.

Discussion

Acupuncture, an ancient Chinese practice, is a growing practice outside of China. In certain countries, acupuncture is even being practiced within public hospitals, which have mainly been principled with Western medicine practices. In this study, we reviewed the reasons why patients choose to utilise acupuncture services within a public hospital. We identified four main thematic classifications to the various factors, namely factors which build around the apparent and perceived patient-centric care within the acupuncture clinic, confidence and trust for the acupuncture clinic, knowledge, beliefs and cultural views regarding acupuncture, as well as the extent of collaboration and integration between the Western medicine and acupuncture disciplines within the hospital.

Demographically, the mean age of our patients was 66.9 years. Current literature reveals that the demographics of individuals who utilise acupuncture varies from community to community. In certain communities, the average age of patients who utilise acupuncture is higher (33,34), whilst in others, younger populations utilise acupuncture services (35,36). The mean age of our participants is relatively high. Austin et al. (34) suggests that an older population utilising acupuncture services is because of individuals paying more attention to their health as they age, possibly due to their increase in ailments with age. The older population which participated can also be explained by Singapore’s ageing population and the geographical location of the participating public hospital within a mature estate (37). Most of our study population were also of Chinese ethnicity, had a University degree and were retired. All individuals interviewed currently hold or previously held a white collared job. There was a good mix of males and females interviewed. Such demographic factors will affect the factors which eventually influence a patient to utilise acupuncture services. Furthermore, amongst the four groups of factors identified, certain groups will stand out more for a certain demographic of individuals as compared to others. However, the influence of demographic patterns in relation to decision making factors on acupuncture utilisation were not analysed in this study. Nevertheless, it should still be realised that such factors do play a role in influencing decisions and health-seeking behaviours.

To a large extent our results corroborate with findings found within the current literature. However, we did find themes not identified within other studies due to the nature of our study which is situated in an acupuncture clinic within a public hospital. In a systematic review conducted by Jakes et al. (38), it was found that one of the main reasons for the utilisation of acupuncture by patients was that of dissatisfaction with conventional medicine. This was coupled with the attraction to holistic and empowering models of healthcare. In our study, we did find participants who were dissatisfied by conventional Western medicine practices. For instance, some participants found that physiotherapy did not help to improve their knee osteoarthritis and consequently sought acupuncture with the hope of delaying or even preventing the possibility of a total knee replacement. However, being in the setting of a public hospital, there were a sizable number of participants who found that acupuncture was complementary to Western medicine and that a good optimisation of the strengths of each practice could benefit their overall health. With this realisation, some patients who utilised the acupuncture services within the public hospital felt empowered by both the option of acupuncture and Western medicine provided by the public hospital in terms of the management of their ailments.

With a certain amount of integration between acupuncture and Western medicine within the public hospital, the concept of a holistic therapeutic model was brought up. However, this was different from that described by Jakes et al in his review, which revolved around three pillars, namely, holism, patient-practitioner relationship as well as self-care and personal responsibility. Many participants in our study brought up the centricity of the patient-practitioner relationship within acupuncture and how it contributed to a superior service as a whole. Several studies have described such a relationship as central to the overall therapeutic experience (39-43). However, the concept of holism, which revolves around the finely integrated aspects of body, mind, spirit, social relationships and wider environment, was not brought up. Self-care and personal responsibility was only discussed with few participants. However, other concepts such as utilising the strengths of various medical and health practices, as well as collaborative medicine were brought up. In some sense, the therapeutic model described in this study is unique to the setting of public hospitals. This is most probably attributed to the integrated infrastructure and shared systems noted within various departments in public hospitals.

In all, we noted that the four factor groups can be further classified into demand-side factors and supply-side factors (Figure 1). This classification can help simplify the analysis of factors when looking into designing solutions to increase utilisation of acupuncture services. Barriers such as cost structures have to be tackled at a hospital infrastructure level. Improved patient centricity in care should occur at the clinic level. However, issues such as building trust and changing behaviour as well as increasing knowledge should be tackled realising that such issues are demand-side issues. Consequently, the best way to approach such issues are via increased outreach to patients, whether in the form of more reading material or more educational talks. In all, a structured approach to understanding the factors which influence a patient into utilising acupuncture services will eventually allow for more structured and logical solutions to increase utilisation of acupuncture services.

Despite the various findings from our study, we noted that there were some limitations to our study. Firstly, we only interviewed patients from one acupuncture clinic situated in a single public hospital. Furthermore, our study was affected by the absence of views from non-responders. The viewpoints of individuals who did not attend the clinic at all, for instance, strong proponents of Western medical practices, were also not taken into consideration. It is thus recommended that future studies aim to survey a broader variety of individuals from multiple acupuncture clinics. Every clinic has its own unique service delivery system and this study mostly captures views pertaining to such systems available in only one clinic. Participants should have also been provided the opportunity vet through our written transcripts and to provide feedback on the findings. Future studies should also look into interviewing individuals who do not attend the acupuncture clinic as well as Western medicine practitioners and acupuncturists. It is hope that with such a methodology, more barriers to acupuncture utilisation can be identified.

Conclusions

The factors which influence patients in eventually choosing acupuncture for the management of their ailments within a public hospital include factors which build around the apparent and perceived patient-centric care within the acupuncture clinic, confidence and trust for the acupuncture clinic, knowledge, beliefs and cultural views regarding acupuncture, as well as the extent of collaboration and integration between the Western medicine and acupuncture disciplines within the hospital. This study also revealed certain factors for patient use of acupuncture which have not been identified in acupuncture utilisation studies not within the public hospital setting. This includes increased confidence in the acupuncture services, convenience, as well as increased collaboration and integration of services. Considering the increase in evidence to suggest the efficacy of acupuncture in managing a variety of ailments and improving health, these factors can be optimised upon in attempting to change health-seeking behaviours to increase the utilisation of acupuncture.

Supplementary

In-depth interview guide:

- Rapport building

- How has your health been?

- On a scale of 1-5, how would you grade your health, where 1 means that your health is very poor, and 5 means your health is excellent (Self-reporting of health status to appreciate better and assess health impact and musculoskeletal pain/injury severity).

- Could you describe the pain you are feeling now/could you describe the injury you have attained?

- How long have you been experiencing the severity of the pain/injury?

- Have you seen a western medicine doctor recently for your medical issue?

- Other than this current visit, have you seen an acupuncturist or traditional medicine practitioner recently for your medical issue?

- Currently, what do you do to take care of your health? What helps you? What hinders you?

- Access to healthcare

- What do you usually do when you are sick?

- Do you see a western doctor?

- Do you see a traditional medicine practitioner?

- Questions about health beliefs and other barriers/enablers to healthcare

- What are your personal beliefs about healthcare in Singapore? Do any of these beliefs affect the way you see healthcare (see a doctor)

- What makes you want to/not want to see a doctor?

- Have you ever seen a doctor when you were not sick? Why?

- Are there any cultural and/or religious reasons that affect the way you seek healthcare? Do/would you see a Western doctor in your home country? Why? What other forms of healthcare (alternative treatment) do you seek in your homeland?

- What do you feel about western medicine and alternative medicine practices?

- Quality

- What do you think of the quality of services made available to you? Are they sufficient? Why/why not?

- How can the quality of services be improved?

- Financial issues

- How do you pay for your medical services? What are the sources of financial help?

- To what extent does having to pay influence your consumption? Of healthcare in general, medication, investigations?

- Are there any restrictions to you being able to afford medical services?

- Service

- What was your experience like when you visited a clinic for medical help? Describe the experience and the impact on you (e.g., did you discontinue seeking medical help, did you turn to other venues, did you continue visiting the clinic)

- Knowledge

- Do you know what services are available for you?

- Healthcare (subsidised community clinics)

- Financial

- Social (counselling, skills development, pro bono legal advice)

- Where do you obtain information about health care, healthy lifestyle habits, common diseases, and other health related information?

- How much do you think you know? (Ask two or more probing questions about healthy lifestyle habits and common diseases to evaluate knowledge)

- Do you think this information is important to you?

- Would you like to be better informed? How much would you like to know?

- Which source would you trust the most?

- How do you use this information in your life?

- What else are you willing to do to improve your health?

- If you were provided with access to information about health care, healthy lifestyle habits, and other health related information

- Are you able to understand the written material? If you don’t, did you try to find a way to understand? How? (Do you get the content translated?)

- Are you able to understand the spoken content? If you don’t, did you try to find a way to understand? How? (Do you ask your friends, or seek other advice?)

- Consulting a western medicine doctor

- What hinders you from consulting a western medicine doctor?

- What hindered you from consulting a western medicine doctor for your musculoskeletal pain? Are there factors which enable/ help you decide (to) consult a western medicine doctor?

- Consulting traditional medicine practitioners/acupuncturists

- What factors enable/ help you decide (to) consult a traditional medicine practitioner/ acupuncturist?

- Are there factors which hinder you from consulting a traditional medicine practitioner/ acupuncturist

- Patient’s perceived satisfaction

- What do you think about the clinical service and care provided by acupuncturists?

- Discuss the overall care

- Discuss the general environment

- Discuss the waiting time

- Discuss the information and advice

- Discuss the cost of services and treatment

- Discuss the perceived benefits from services and treatment

- How satisfied are you with the acupuncturist?

- Discuss the amount of time spent with the doctor

- Discuss the acupuncturist’s openness to questions

- Discuss whether the acupuncturist took into consideration the personal view of the patient

- Discuss the competency of the acupuncturist and other service providers

- Discuss the ease and confidence with the acupuncturist

- Cultural beliefs

- How strongly do you believe in traditional theories regarding health, illness and remedies?

- How far do you agree with the concepts of ‘Yin’ and ‘Yang’?

- How far do you agree with the concept of ‘harmony of different humours’?

- How far do you agree with the concept of ‘balance of energies’?

- Other questions

- Are you taking any medications currently for your pain?

- What changes would you like to see in Singapore’s healthcare system?

- What changes would you like to see in Singapore’s acupuncture clinics and systems?

Do take into consideration possible factors such as socioeconomic status, third party decisions made by individuals (e.g., caregivers) and recommendations by family, close relatives and/or friends.

The following questions have to be asked accordingly depending on whether patient has previously seen an acupuncturist before. If the patient has seen a western medicine practitioner before for his/her musculoskeletal pain, ask the same questions, replacing the term ‘acupuncturist’ with ‘western medicine doctors’.

Ask the following questions where applicable

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Hseuh CC, O'Connor J. Acupuncture: A Comprehensive Text. Chicago, IL: Eastland Press, 1981.

- White A, Hayhoe S, Hart A, et al. Adverse events following acupuncture: prospective survey of 32 000 consultations with doctors and physiotherapists. BMJ 2001;323:485-6. [PubMed]

- MacPherson H, Thomas K, Walters S, et al. The York acupuncture safety study: prospective survey of 34 000 treatments by traditional acupuncturists. BMJ 2001;323:486-7. [PubMed]

- Wonderling D, Vickers AJ, Grieve R, et al. Cost effectiveness analysis of a randomised trial of acupuncture for chronic headache in primary care. BMJ 2004;328:747. [PubMed]

- Willich SN, Reinhold T, Selim D, et al. Cost-effectiveness of acupuncture treatment in patients with chronic neck pain. Pain 2006;125:107-13. [PubMed]

- Ratcliffe J, Thomas KJ, MacPherson H, et al. A randomised controlled trial of acupuncture care for persistent low back pain: cost effectiveness analysis. BMJ 2006;333:626. [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Acupuncture: Review and Analysis Reports on Controlled Clinical Trials. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2002.

- Vickers AJ, Linde K. Acupuncture for chronic pain. JAMA 2014;311:955-6. [PubMed]

- Suzuki M, Yokoyama Y, Yamazaki H. Research into acupuncture for respiratory disease in Japan: a systematic review. Acupunct Med 2009;27:54-60. [PubMed]

- Pfab F, Schalock PC, Napadow V, et al. Acupuncture for allergic disease therapy--the current state of evidence. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2014;10:831-41. [PubMed]

- Garcia MK, McQuade J, Haddad R, et al. Systematic review of acupuncture in cancer care: a synthesis of the evidence. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:952-60. [PubMed]

- Lim DC, Chen W, Cheng LN, et al. Acupuncture for polycystic ovarian syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011.CD007689. [PubMed]

- Lin Y. Acupuncture treatment for insomnia and acupuncture analgesia. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1995;49:119-20. [PubMed]

- Kalavapalli R, Singareddy R. Role of acupuncture in the treatment of insomnia: a comprehensive review. Complement Ther Clin Pract 2007;13:184-93. [PubMed]

- Helms JM. Acupuncture Energetics: A Clinical Approach for Physicians, 1st edition. Berkely: Medical Acupuncture Publishers, 1995.

- World Health Organization. WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy 2014-2023. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2013.

- Zhuang Y, Xing JJ, Li J, et al. History of acupuncture research. Int Rev Neurobiol 2013;111:1-23. [PubMed]

- Loh M. Victoria as a catalyst for western and Chinese medicine. J Royal Hist Soc Vic 1985;56:39-46.

- Frass M, Strassl RP, Friehs H, et al. Use and acceptance of complementary and alternative medicine among the general population and medical personnel: a systematic review. Ochsner J 2012;12:45-56. [PubMed]

- European Commission for Homeopathy (ECH). Report on Swiss Report on the Complementary Medicine Evaluation Programme (PEK). Available online: http://www.portaldehomeopatia.com.br/documentos/Report%20on%20PEK%20study.pdf

- Dale J. Acupuncture practice in the UK. Part 1: report of a survey. Complement Ther Med 1997;5:215-20.

- Thomas KJ, Coleman P, Nicholl JP. Trends in access to complementary or alternative medicines via primary care in England: 1995-2001 results from a follow-up national survey. Fam Pract 2003;20:575-7. [PubMed]

- Tehrani-Banihashemi S, Asghari-fard H, Haghdost A, et al. Application of complementary and traditional medicine in Tehran city. Payesh 2005;7:355-62.

- Xue CC, Zhang AL, Yang AW, et al. Recent developments of acupuncture in Australia and the way forward. Chin Med 2009;4:7. [PubMed]

- Nourshahi M, Ahmadizad S, Nikbakht H, et al. The effects of triple therapy (acupuncture, diet and exercise) on body weight: a randomized, clinical trial. Int J Obes (Lond) 2009;33:583-7. [PubMed]

- Horrigan BJ. New NHIS survey reveals that 38% of American adults use CAM. Explore (NY) 2009;5:71-3. [PubMed]

- Bishop FL, Yardley L, Lewith GT. Treat or treatment: a qualitative study analyzing patients' use of complementary and alternative medicine. Am J Public Health 2008;98:1700-5. [PubMed]

- Nichol J, Thompson EA, Shaw A. Beliefs, decision-making, and dialogue about complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) within families using CAM: a qualitative study. J Altern Complement Med 2011;17:117-25. [PubMed]

- Norheim AJ. Integrated medicine in London. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2011;131:714-5. [PubMed]

- Jacobsen R, Fønnebø VM, Foss N, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine within Norwegian hospitals. BMC Complement Altern Med 2015;15:275. [PubMed]

- Salomonsen LJ, Skovgaard L, la Cour S, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine at Norwegian and Danish hospitals. BMC Complement Altern Med 2011;11:4. [PubMed]

- Carruzzo P, Graz B, Rodondi PY, et al. Offer and use of complementary and alternative medicine in hospitals of the French-speaking part of Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly 2013;143:w13756. [PubMed]

- Yang LH, Du YH, Li B. Demographic characteristics of acupuncture outpatient based on clinical investigation. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu 2013;33:1118-22. [PubMed]

- Austin S, Ramamonjiarivelo Z, Qu H, et al. Acupuncture Use in the United States: Who, Where, Why, and at What Price? Health Mark Q 2015;32:113-28. [PubMed]

- Hwang JH, Han DW, Yoo EK, et al. The utilisation of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) among ethnic minorities in South Korea. BMC Complement Altern Med 2014;14:103. [PubMed]

- Patel A, Standen C. An Auckland-based student acupuncture clinic patient profile and utilisation study. N Z Med J 2014;127:134-7. [PubMed]

- Population Trends 2014. Available online: http://www.singstat.gov.sg/docs/default-source/default-document-library/publications/publications_and_papers/population_and_population_structure/population2014.pdf

- Jakes D, Kirk R, Muir L. A qualitative systematic review of patients' experiences of acupuncture. J Altern Complement Med 2014;20:663-71. [PubMed]

- Cassidy CM. Chinese medicine users in the United States. Part II: Preferred aspects of care. J Altern Complement Med 1998;4:189-202. [PubMed]

- Gould A, MacPherson H. Patient perspectives on outcomes after treatment with acupuncture. J Altern Complement Med 2001;7:261-8. [PubMed]

- Bishop FL, Barlow F, Coghlan B, et al. Patients as healthcare consumers in the public and private sectors: a qualitative study of acupuncture in the UK. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:129. [PubMed]

- Hughes JG. "When I first started going I was going in on my knees, but I came out and I was skipping": exploring rheumatoid arthritis patients' perceptions of receiving treatment with acupuncture. Complement Ther Med 2009;17:269-73. [PubMed]

- Paterson C, Britten N. The patient's experience of holistic care: insights from acupuncture research. Chronic Illn 2008;4:264-77. [PubMed]