Discussion on the rationality of FIGO 2018 stage IIIC for cervical cancer with oncological outcomes: a cohort study

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common malignant tumor in women (1). The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging system is the main system used for cervical cancer staging. The previous FIGO staging system did not consider lymph node metastasis, but in 2018 FIGO staging underwent a major update, with lymph node metastasis included in staging principles. The updated FIGO staging in 2018 was called FIGO 2018. Cervical cancer patients with lymph node metastasis are classified as stage IIIC, and imaging is recognized as evidence in the diagnosis of lymph node metastasis by pathological examination (2,3).

Previous studies have reported that the 5-year survival rates for FIGO 2018 stage IIIA, IIIB, IIIC1, and IIIC2 cervical cancer were 40.7%, 41.4%, 60.8%, and 37.5%, respectively (4). Other studies have found similar results, with 5-year survival rates for stage IIIA, IIIB, and IIIC1 cervical cancer at 46.0%, 42.6%, and 62.1%, respectively (P<0.001) (5). At present, the diagnosis of stage IIIC does not consider local tumor factors, but related studies comparing the different local factors (T1, T2, T3) of stage IIIC1 tumors have found that there are differences in the oncological outcomes (5,6). But this similar study did not limit the treatment methods of the included cases, nor did it distinguish between T2a and T2b, because the treatment methods of the two groups of cases are quite different (5).

However, these studies focused solely on stage IIIC1, and there is still a lack of research using the Chinese Cervical Cancer Clinical (Four-C) study database for stage IIIC that compares the overall survival (OS) rate and tumor-free survival rate based on local tumor factors. Therefore, we used Four-C database to compare the 5-year OS and DFS for stage IIIA, IIIB, and IIIC cervical cancer patients. Stage IIIC patients were divided into 5 subgroups based on local tumor factors: T1a, T1b, T2a, T2b, and T3. In addition, differences in the T3 group were further explored. We present the following article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://atm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/atm-21-6374/rc).

Methods

Data source

This study was a multicenter, retrospective, observational study, and the data used in this study originated from the Four-C database, a cervical cancer-specialized disease database (n=63,926) that covers consecutive patients with cervical cancer from 47 hospitals in mainland China treated between January 2004 and December 2018.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nanfang Hospital affiliated with Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China (ethics approval number: NFEC-2017-135). The ethics committee determined that no consent from the participation was necessary as the study was retrospective. The study protocol was registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (Identifier: CHiCTR1800017778).

We consulted relevant medical records, collected patients’ general clinical data, preoperative laboratory and pathological results, surgery-related data, preoperative and postoperative adjuvant treatment data, postoperative pathological data, and follow-up data. As the diagnosis dates of the cases spanned from 2004 to 2018, staging correction was carried out in accordance with the FIGO 2018 staging principles (2,3). Follow-up was conducted by specially trained gynecologists, with the process supervised and managed by specialized personnel. Details of the data collection method are provided in literature previously published by the team (7-12).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Tumor factors from the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging system (13) were used to divide the IIIC stage patients into 5 groups: T1a, T1b, T2a, T2b and T3.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (I) patients age ≥18 years; (II) cervical cancer diagnosed by cervical biopsy; (III) squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, or adenosquamous carcinoma based on histology; (IV) FIGO 2018 stage IIIA/IIIB/IIIC; (V) treatment: patients with stage IIIA and IIIB who received radiation therapy (radiotherapy dose ≥45 Gy); stage IIIC patients in groups T2b and T3 who received radiation therapy (radiotherapy dose ≥45 Gy); stage IIIC patients in groups T1a, T1b, and T2a who received radical surgery (Q-M type B or type C radical hysterectomy + pelvic lymphadenectomy ± para-aortic lymphadenectomy and adjuvant treatment performed in accordance with Sedlis standards); and (VI) patients given radiation therapy due to the status of the lymph nodes based on pretreatment imaging examinations, and patients treated with radical surgery that determined the status of the lymph nodes based on postoperative pathological examinations.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (I) pregnancy; (II) cervical stump cancer; (III) cervical cancer combined with other malignancies; (IV) loss to follow-up; and (V) not meeting the inclusion criteria.

Observational indicators

The 5-year OS and 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) rates of cervical cancer patients were the main outcome observations of our study. The cutoff point for long-term oncological outcome observations was five years. OS was defined as the time period from the date of diagnosis to death from any cause or the last effective follow-up. DFS was defined as the time period from diagnosis to death, recurrence, or the last effective follow-up.

Statistical analysis

There were no missing data among the included cases. Continuous data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (), and categorical data are presented as percentages (%). Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to describe the change in survival outcomes. Cox proportional risk regression models were used to adjust for variables and to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the effects of stage on the 5-year OS and DFS rates. The statistical software used was SPSS 26.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Data filtering process

From the 63,926 cases of cervical cancer in the Four-C database, a total of 5,212 cases were included in this study, of which 251 cases were stage IIIA, 1,824 cases were stage IIIB, and 3,137 cases were stage IIIC (Figure 1). The median follow-up time was 40 months, including 38 months for stage IIIA, 42 months for stage IIIB, and 39 months for stage IIIC. Based on the T principles of TNM staging, the stage IIIC cases (n=3,137) were divided into 5 groups: T1a (n=4), T1b (n=861), T2a (n=587), T2b (n=641), and T3 (n=1,044) (Figure 1).

Comparison of oncological outcomes for patients with stage IIIA, IIIB, and IIIC disease

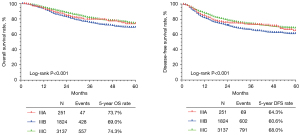

The clinicopathologic characteristics of patients with stage IIIA (n=251), stage IIIB (n=1,824), and stage IIIC disease (n=3,137) are shown in Table 1. There was a statistically significant difference in the age and histological type of patients among the stage IIIA, IIIB, and IIIC groups (P<0.001). Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that there were statistically significant differences among the stage IIIA, IIIB, and IIIC groups in 5-year OS (73.7%, 69.0%, and 74.3%, respectively, P<0.001) and 5-year DFS (64.3%, 60.6%, and 68.0%, respectively, P<0.001) (Figure 2).

Table 1

| Characteristics | IIIA (n=251) | IIIB (n=1,824) | IIIC (n=3,137) | P | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||

| Age (years) | 59.2±10.566 | 55.26±10.629 | 51.52±10.642 | <0.001 | |||||

| Histological type | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 244 | 97.2 | 1,755 | 96.2 | 2,910 | 92.8 | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 6 | 2.4 | 48 | 2.6 | 164 | 5.2 | |||

| Adenosquamous | 1 | 0.4 | 21 | 1.2 | 63 | 2.0 | |||

Cox multivariate survival analysis was performed on a total of 5,212 patients with stage IIIA, IIIB, and IIIC disease. The results showed that older age was associated with a lower 5-year OS (HR =1.018, 95% CI: 1.012–1.024, P<0.001) and DFS (HR =1.010, 95% CI: 1.005–1.015, P<0.001). Compared with squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma was associated with a lower 5-year OS (HR =1.763, 95% CI: 1.361–2.282, P<0.001) and DFS (HR =1.727, 95% CI: 1.383–2.155, P<0.001), while adenosquamous carcinoma was not significantly correlated with 5-year OS (HR =1.186, 95% CI: 0.744–1.892, P=0.474) or DFS (HR =1.326, 95% CI: 0.911–1.929, P=0.140). Stage IIIA had no significant correlation with the 5-year OS (HR =0.998, 95% CI: 0.739–1.349, P=0.990) or DFS (HR =1.081, 95% CI: 0.843–1.387, P=0.539). Compared with stage IIIC, stage IIIB was associated with a lower 5-year OS (HR =1.291, 95% CI: 1.135–1.468, P<0.001) and DFS (HR =1.354, 95% CI: 1.215–1.508, P<0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2

| Variables | 5-year OS | 5-year DFS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | ||

| Age (years) | 1.018 | 1.012–1.024 | <0.001 | 1.010 | 1.005–1.015 | <0.001 | |

| Histological type | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 1 (Ref) | – | – | 1 (Ref) | – | – | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 1.763 | 1.361–2.282 | <0.001 | 1.727 | 1.383–2.155 | <0.001 | |

| Adenosquamous | 1.186 | 0.744–1.892 | 0.474 | 1.326 | 0.911–1.929 | 0.140 | |

| FIGO 2018 stage | – | <0.001 | – | <0.001 | |||

| IIIC | 1 (Ref) | – | – | 1 (Ref) | – | – | |

| IIIA | 0.998 | 0.739–1.349 | 0.990 | 1.081 | 0.843–1.387 | 0.539 | |

| IIIB | 1.291 | 1.135–1.468 | <0.001 | 1.354 | 1.215–1.508 | <0.001 | |

OS, overall survival; DFS, disease-free survival; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

Comparison of oncological outcomes of different local tumor factors in patients with stage IIIC

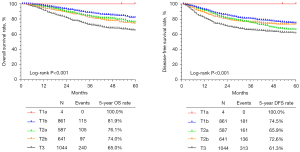

Based on the T principles of TNM staging, patients with stage IIIC (n=3,137) disease were divided into the T1a group (n=4), T1b group (n=861), T2a group (n=587), T2b group (n=641), and T3 group (n=1,044). A comparison of their clinicopathological characteristics is shown in Table 3. There was a statistically significant difference in age and histological type among patients in the T1a, T1b, T2a, T2b, and T3 groups (P<0.001). Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that there were significant differences in the 5-year OS (100.0%, 81.9%, 76.1%, 74.0%, and 65.0%, P<0.001) and DFS (100.0%, 74.5%, 65.9%, 72.6%, and 61.3%, P<0.001) among the T1a, T1b, T2a, T2b, and T3 groups, respectively (Figure 3).

Table 3

| Characteristics | T1a (n=4) | T1b (n=861) | T2a (n=587) | T2b (n=641) | T3 (n=1,044) | P | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||||

| Age (years) | 39±5.099 | 46.8±9.018 | 49.93±9.557 | 54.34±10.689 | 54.61±10.826 | <0.001 | |||||||||

| Histological type | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 4 | 100.0 | 747 | 86.8 | 533 | 90.8 | 620 | 96.7 | 1,006 | 96.4 | |||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 0 | 0.0 | 80 | 9.3 | 38 | 6.5 | 17 | 2.7 | 29 | 2.8 | |||||

| Adenosquamous | 0 | 0.0 | 34 | 3.9 | 16 | 2.7 | 4 | 0.6 | 9 | 0.9 | |||||

Cox multivariate survival analysis was performed on 3,717 patients with stage IIIC disease. The results showed that age was correlated with the 5-year OS (HR =1.005, 95% CI: 0.997–1.013, P=0.225), while there was no significant correlation with DFS (HR =0.999, 95% CI: 0.992–1.006, P=0.833). Compared with squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma was associated with a lower 5-year OS (HR =1.948, 95% CI: 1.416–2.679, P<0.001) and DFS (HR =1.713, 95% CI: 1.297–2.262, P<0.001). Compared with squamous cell carcinoma, adenosquamous cell carcinoma was associated with a lower 5-year OS (HR =1.779, 95% CI: 1.042–3.039, P=0.035), but there was no significant correlation with the 5-year DFS (HR =1.419, 95% CI: 0.886–2.273, P=0.145). The T1a group had no significant correlation with 5-year OS (HR =0.923, P<0.001) or DFS (HR =0.923, P=0.001), while groups T1b, T2a (HR =1.405, 95% CI: 1.076–1.834, P=0.012), T2b (HR =1.592, 95% CI: 1.203–2.108, P=0.001), and T3 (HR =2.495, 95% CI: 1.971–3.157, P<0.001) were associated with a lower 5-year OS. Groups T2a (HR =1.372, 95% CI: 1.108–1.699, P=0.004), T2b (HR =1.337, 95% CI: 1.061–1.684, P=0.014), and T3 (HR =2.015, 95% CI: 1.659–2.446, P<0.001) were associated with a lower DFS (Table 4).

Table 4

| Variables | 5-year OS | 5-year DFS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | ||

| Age (years) | 1.005 | 0.997–1.013 | 0.225 | 0.999 | 0.992–1.006 | 0.833 | |

| Histological type | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 1 (Ref) | – | – | 1 (Ref) | – | – | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 1.948 | 1.416–2.679 | <0.001 | 1.713 | 1.297–2.262 | <0.001 | |

| Adenosquamous | 1.779 | 1.042–3.039 | 0.035 | 1.419 | 0.886–2.273 | 0.145 | |

| Subgroup in stage IIIC | <0.001 | – | <0.001 | ||||

| T1b | 1 (Ref) | – | – | 1 (Ref) | – | – | |

| T1a | <0.001 | – | 0.923 | <0.001 | – | 0.908 | |

| T2a | 1.405 | 1.076–1.834 | 0.012 | 1.372 | 1.108–1.699 | 0.004 | |

| T2b | 1.592 | 1.203–2.108 | 0.001 | 1.337 | 1.061–1.684 | 0.014 | |

| T3 | 2.495 | 1.971–3.157 | <0.001 | 2.015 | 1.659–2.446 | <0.001 | |

OS, overall survival; DFS, disease-free survival; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

This study was based on the data collection of the Four-C database of 47 hospitals and included 5,212 FIGO 2018 stage III cervical cancer patients. We compared oncological outcomes for groups of patients at different stages of disease. Cox multivariate analysis found that stage IIIA had no significant correlation with 5-year OS (HR =0.998, 95% CI: 0.739–1.349, P=0.990) or DFS (HR =1.081, 95% CI: 0.843–1.387, P=0.539). Compared with IIIC, stage IIIB had a lower 5-year OS and was correlated with 5-year OS (HR =1.291, 95% CI: 1.135–1.468, P<0.001) and DFS (HR =1.354, 95% CI: 1.215–1.508, P<0.001). In accordance with the T principles of TNM staging, the IIIC cases were divided into the T1a, T1b, T2a, T2b, and T3 groups. Multivariate analysis indicated that compared with the T1b group, T2a (HR =1.405, 95% CI: 1.076–1.834, P=0.012), T2b (HR =1.592, 95% CI: 1.203–2.108, P=0.001), and T3 were associated with a lower 5-year OS (HR =2.495, 95% CI: 1.971–3.157, P<0.001). T2a (HR =1.372, 95% CI: 1.108–1.699, P=0.004), T2b (HR =1.337, 95% CI: 1.061–1.684, P=0.014), and T3 (HR =2.015, 95% CI: 1.659–2.446, P<0.001) were associated with a lower 5-year DFS. The results of this study showed that the oncological outcome for patients with stage IIIC cervical cancer was better than that for patients with stage IIIB cervical cancer, and that the oncological outcomes for patients with stage IIIC and IIIA cervical cancer were similar. At the same time, there are other studies that consider the parameters of stage IIIC to be unreasonable from an oncological outcome perspective (4,5).

A retrospective study based on the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database (5) included 11,733 stage III cervical cancer patients from 1988 to 2014. In accordance with the FIGO 2018 staging system, patients were divided into stage IIIA (1,033 cases, 8.8%), stage IIIB (3,812 cases, 32.5%), and stage IIIC1 (6,888 cases, 58.7%). Survival analysis found that the 5-year survival rate for stage IIIC1 (62.1%) was better than that of stage IIIA (46.0%) and IIIB (42.6%). Multivariate analysis found that stage IIIC was independent of stage IIIA (adjusted HR =0.88, 95% CI: 0.70–0.98, P=0.018) and stage IIIB (adjusted HR =0.79, 95% CI: 0.74–0.85, P<0.001) with regards to specific survival protective factors. The 5-year-specific survival rate of patients with stage IIIC1 disease was analyzed by subgroup analysis. Based on the T principles of the TNM staging system, patients were divided as follows: 74.8% in the T1 group, 58.7% in the T2 group, and 39.3% in the T3 group. Among them, stage IIIC1 patients had a lower survival rate than T3b patients (when there was no lymph node metastasis in stage IIIB) (38.1% vs. 42.6%, HR =1.12, 95% CI: 1.02–1.22, P=0.013). The study only included stage IIIC1 patients (pelvic lymph node metastasis only, no para-aortic lymph node metastasis) and excluded IIIC2 cases (including abdominal para-aortic lymph node metastasis). However, the patients included in the study were not strictly enrolled or excluded based on treatment methods for the different T groups.

A Korean study (14) analyzed 502 cases of stage IIIC cervical cancer from 2010 to 2015. Survival analysis found that the survival outcome for stage IIIC1 was better than that for stage IIIA, IIIB, and IIIC2 (P<0.001). The IIIC cases were divided into T1, T2, and T3 according to the T principles of TNM staging, and T1 had the best survival outcome, followed by T2, while T3 had the worst (P<0.001). The study did not specify details of the treatment methods for the included cases, and the results are similar to those of our study.

Grigsby’s study (6) analyzed the 5-year PFS of each substage of FIGO 2018, including IIIB (n=72, 55%), IIIC1 (n=380, 62%), IIIC2 (n=140, 35%) (P<0.0001), and IIIA (n=9, 46%). After grouping in accordance with the T principles in TNM staging for IIIC1, it was found that 5-year PFS for T1 was 72%, T2 was 63%, and T3 was 41% (P<0.0001). After grouping for IIIC2, it was found that 5-year PFS for T1 was 62%, T2 was 32%, and T3 was 23% (P=0.01). The study included fewer stage IIIA cases, and it also showed that the 5-year PFS for stage IIIB was between IIIC1 and IIIC2, which is consistent with the results of our study. For the IIIC group comparison, there were significant differences in the 5-year PFS for different T stages, which is also consistent with the results of this study.

Many studies have shown that lymph node metastasis is an important factor affecting the prognosis of cervical cancer (15-18). This conclusion has been confirmed in clinical studies and also has a theoretical basis. In TNM staging, lymph node metastasis is regarded as an independent staging indicator. The establishment of IIIC in the FIGO 2018 staging is indeed an important improvement, but the IIIC stage does not consider local tumor factors. In our study, local tumor factors were subdivided into T1a, T1b, T2a, T2b, and T3 based on the T principles of TNM staging and then compared. Previous research has shown that patients with stage IIIC cervical cancer, with the progression of local tumor factors T1, T2, and T3, have worse oncological outcomes (5,6,14). However, our study was further divided into T2a and T2b cases to compare oncological outcomes with a specific research value. At present, the recommended treatment methods for FIGO stages IIA and IIB are different. Patients in stage IIB are recommended to undergo radical radiotherapy and chemotherapy. The recommended treatment methods for patients in stage IIA include surgical treatment, radical radiotherapy, and chemotherapy. The T2a patients included in this study received radical surgery, and group T2b patients received radical radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

We recognize several limitations in our study. As a retrospective study, there were potential biases and missing information. There was no further classification of IIIC stage cases into stages IIIC1 and IIIC2 for subgroup analysis. Group T2b and T3 cases were categorized according to pretreatment imaging studies, and judgments were based on a particular specificity and sensitivity.

According to the principle of FIGO2018 staging, stage IIIC did not distinguish local tumor factors. However, our study found that different local tumor factors have different oncological outcomes. Moreover, with the development of local tumor factors, the oncology outcome was worse. Therefore, we suggest that stage IIIC should be further grouped according to local tumor factors, and the recommended treatment methods for different groups should not be the same.

Our study found that the oncological outcome for FIGO 2018 stage IIIC cervical cancer was better than that of stage IIIB cervical cancer and was comparable to the oncological outcome for stage IIIA cervical cancer. The oncological outcome for stage IIIC is related to local tumor factors. As the local tumor progresses, the oncological outcome worsens. Stage IIIC may need to be redefined based on local tumor factors, and more prospective studies need to be performed in the future.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bin Ling (China-Japan Friendship Hospital), Lixin Sun and Hongwei Zhao (Shanxi Cancer Hospital), Jihong Liu and Lizhi Liang (Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center), Lihong Lin and Yu Guo (Anyang Tumor Hospital), Li Wang (The Affiliated Tumor Hospital of Zhengzhou University), Weidong Zhao (Anhui Provincial Cancer Hospital), Yan Ni (The Yuncheng Central Hospital of Shanxi Province), Wentong Liang and Donglin Li (Guizhou Provincial People’s Hospital), Xuemei Zhan and Mingwei Li (Jiangmen Central Hospital), Weifeng Zhang (Ningbo Women & Children’s Hospital), Peiyan Du (The Affiliated Cancer Hospital and Institute of Guangzhou Medical University), Ziyu Fang (Liuzhou Workers’ Hospital), Rui Yang (Shenzhen Hospital of Peking University), Long Chen (Qingdao Municipal Hospital), Encheng Dai and Ruilei Liu (Linyi People’s Hospital), Yuanli He and Mubiao Liu (Zhujiang Hospital, Southern Medical University), Jilong Yao and Zhihua Liu (Shenzhen Maternity & Child Health Hospital), Xueqin Wang (The Fifth Affiliated Hospital of Southern Medical University), Anwei Lu (Maternal and Child Health Hospital of Guiyang Province), Shuangling Jin (Peace Hospital affiliated to Changzhi Medical College), Ben Ma (Guangzhou First People’s Hospital), Zhonghai Wang (Shenzhen Nanshan People’s Hospital), Lin Zhu (The Second Hospital of Shandong University), Hongxin Pan (The Third Affiliated Hospital of Shenzhen University), Qianyong Zhu (No. 153. Center Hospital of Liberation Army/Hospital No. 988 of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Joint Support Force), Dingyuan Zeng and Zhong Lin (Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital of Liuzhou), Xiaohong Wang (Laiwu People’s Hospital/Jinan City People’s Hospital), and Bin Zhu (The Affiliated Yiwu Women and Children Hospital of Hangzhou Medical College) for their contribution during the data collection.

Funding: This study received funding from the National Science and Technology Support Program of China (Grant No. 014BAI05B03), the National Natural Science Fund of Guangdong (Grant No. 2015A030311024), and the Science and Technology Plan of Guangzhou (Grant No. 158100075).

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editor (Danbo Wang) for the series “New Progress and Challenge in Gynecological Cancer” published in Annals of Translational Medicine. The article has undergone external peer review.

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://atm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/atm-21-6374/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://atm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/atm-21-6374/dss

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://atm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/atm-21-6374/coif). The series “New Progress and Challenge in Gynecological Cancer” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nanfang Hospital affiliated with Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China (ethics approval number: NFEC-2017-135). The ethics committee determined that no consent from the participation was necessary as the study was retrospective.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:394-424. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bhatla N, Berek JS, Cuello Fredes M, et al. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the cervix uteri. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2019;145:129-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Corrigendum to. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the cervix uteri Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2019;147:279-80. [Int J Gynecol Obstet 145(2019) 129-135]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wright JD, Matsuo K, Huang Y, et al. Prognostic Performance of the 2018 International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics Cervical Cancer Staging Guidelines. Obstet Gynecol 2019;134:49-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Matsuo K, Machida H, Mandelbaum RS, et al. Validation of the 2018 FIGO cervical cancer staging system. Gynecol Oncol 2019;152:87-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grigsby PW, Massad LS, Mutch DG, et al. FIGO 2018 staging criteria for cervical cancer: Impact on stage migration and survival. Gynecol Oncol 2020;157:639-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang XR, Li ZQ, Sun LX, et al. Cohort Profile: Chinese Cervical Cancer Clinical Study. Front Oncol 2021;11:690275. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li Z, Chen C, Liu P, et al. Comparison of oncological outcomes and major complications between laparoscopic radical hysterectomy and abdominal radical hysterectomy for stage IB1 cervical cancer with a tumour size less than 2 cm. Eur J Surg Oncol 2021;47:2125-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li W, Liu P, Zhao W, et al. Effects of preoperative radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy on postoperative pathological outcome of cervical cancer--from the large database of 46,313 cases of cervical cancer in China. Eur J Surg Oncol 2020;46:148-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen B, Ji M, Li P, et al. Comparison between robot-assisted radical hysterectomy and abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer: A multicentre retrospective study. Gynecol Oncol 2020;157:429-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen C, Wang W, Liu P, et al. Survival After Abdominal Q-M Type B versus C2 Radical Hysterectomy for Early-Stage Cervical Cancer. Cancer Manag Res 2019;11:10909-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li P, Chen L, Ni Y, et al. Comparison between laparoscopic and abdominal radical hysterectomy for stage IB1 and tumor size <2 cm cervical cancer with visible or invisible tumors: a multicentre retrospective study. J Gynecol Oncol 2021;32:e17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Olawaiye AB, Baker TP, Washington MK, et al. The new (Version 9) American Joint Committee on Cancer tumor, node, metastasis staging for cervical cancer. CA Cancer J Clin 2021;71:287-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shin W, Ham TY, Park YR, et al. Comparing survival outcomes for cervical cancer based on the 2014 and 2018 International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics staging systems. Sci Rep 2021;11:6988. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Narayan K, Fisher RJ, Bernshaw D, et al. Patterns of failure and prognostic factor analyses in locally advanced cervical cancer patients staged by positron emission tomography and treated with curative intent. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2009;19:912-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang W, Zhang F, Hu K, et al. Image-guided, intensity-modulated radiation therapy in definitive radiotherapy for 1433 patients with cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2018;151:444-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Song S, Kim JY, Kim YJ, et al. The size of the metastatic lymph node is an independent prognostic factor for the patients with cervical cancer treated by definitive radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol 2013;108:168-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Okazawa M, Mabuchi S, Isohashi F, et al. The prognostic significance of multiple pelvic node metastases in cervical cancer patients treated with radical hysterectomy plus adjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2012;22:490-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

(English Language Editor: A. Muylwyk)