Simulated operations (SOs) apply mechanical support to structures to confirm symptom causation

Highlight box

Key findings

• “Simulated operations” (SOs) mechanically support structures to confirm symptom causation and to help predict symptom outcomes of surgical repair of that structure.

What is known and what is new?

• SOs are not in common use.

• Unilateral support of the pubourethral ligament at midurethra with a hemostat can prevent urine loss on coughing [stress urinary incontinence (SUI)]; uterosacral ligament support in the posterior fornix with a speculum can relieve pain and urge symptoms.

What is the implication and what should change now?

• Disappearance of SUI, urge, and pain by SOs, is direct proof of the Integral Theory’s predictions for ligament causation. SOs take a few seconds to perform, provide much information, and should be part of a standard vaginal examination.

Introduction

Foreword to the 1990 Integral Theory (IT).

“To me, it has always been obvious that, in general, the reason behind female urinary incontinence has to be looked for outside the bladder i.e., in the structures supporting the urethra and bladder neck—specifically ligaments, pelvic floor muscles, and vagina. If symptoms of urinary incontinence arise from a dysfunctional anatomy in the aforementioned structures then function should come with restoration of anatomy.”

Axel Ingelman-Sundberg, Karolinska Institutet 1990.

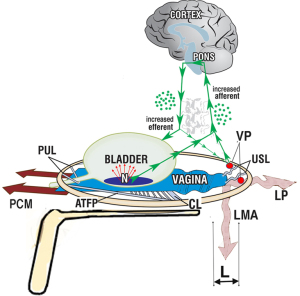

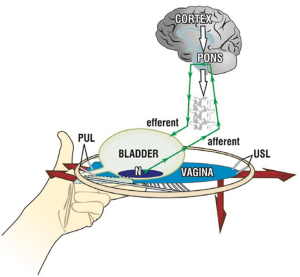

The foreword distils the basis of simulated operations (SOs): urinary control is from outside the bladder, from pelvic muscles contracting against them. If a ligament is weak, say from deficient collagen, the pelvic muscles which contract against them also weaken, so they cannot close the urethra (causing stress incontinence), open it (causing emptying difficulties), or stretch the vagina like a trampoline to prevent premature activation of the micturition reflex (causing urge incontinence) (1).

What are SOs?

SOs mimic a surgical operation. SOs are used to confirm that a particular ligament is causing a particular symptom or prolapse. SOs mechanically support pubourethral and uterosacral ligaments (USLs), the vagina, (for bladder base stretch receptors) while the effect on symptoms [urge, stress urinary incontinence (SUI), pain] is observed. The concept of SOs has expanded to monitoring anatomical changes by ultrasound, and pressure changes on urodynamic graphs. SOs are useful in preoperatively deciding whether to proceed with ligament repair surgery in women who have severe symptoms, but only minimal prolapse. SOs provide the evidence for the IT’s statement that ligament laxity is a major cause of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTSs), prolapse, and chronic pelvic pain (CPP).

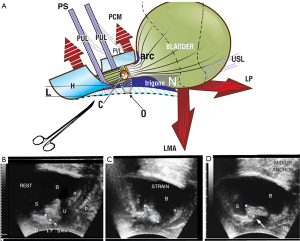

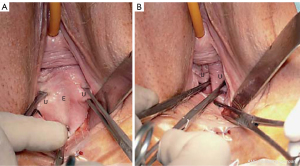

The first SO for mechanical control of SUI was performed in 1986 (Figure 1) (see Video S1). The 1986 observations provided the insights which led to the midurethral sling; specifically, urine loss on coughing could be controlled by mechanical support of the pubourethral ligaments (PULs) by a hemostat, and, to a lesser extent, plication of the suburethral vaginal “hammock” (demonstrated in Video S1). This observation spawned the hypothesis that loose, collagen deficient PULs may be the cause of SUI (1). The hypothesis was later validated by a series of experiments which led to the IT (1) and the prototype midurethral sling and the tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) operation (1,2). Instead of the hemostat, a tape was used to create new collagen to reinforce PULs (3).

An anatomical rationale for SOs

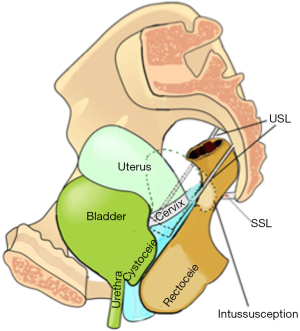

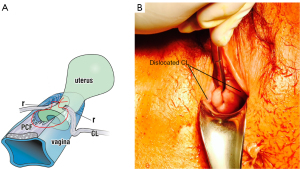

With reference to Figure 2A, the circles 1–4 pictorially represent the structures damaged by the head as it descends down the vaginal birth canal. At each level of the birth canal, the head may damage parts of the vagina itself and the ligaments which suspend the organs, to cause prolapse of the bladder, bowel, and uterus. The same damaged ligaments, contained within the circles 1–4, may cause the symptoms of bladder/bowel and CPP dysfunctions, some of which can be directly tested by SOs. The symptoms caused by the damaged ligaments(circles 1–4) are detailed in the diagnostic algorithm (Figure 2B). The numbers and ligaments in each of the four circles 1–4, correlate with the same numbers in the three columns of the diagnostic algorithm (Figure 2B).

How SOs test (and demonstrate) the predictions of the IT

“Support the structure and you will improve the function” (IT).

What SOs do is to provide mechanical support so the ligament can do its job. The ligaments damaged at the four levels of the vaginal canal, the PUL, the cardinal ligament (CL), the USL, and the perineal body (PB) (Figure 2A), weaken and stretch when forces are applied to them, from whatever the source, as does the PUL (ultrasound, Figure 1). The IT predications that, “Stress, urge and chronic pelvic pain, for different reasons, are mainly caused by laxity in the vagina or its supporting ligaments”, can be directly tested during standard vaginal examination by mechanically supporting either the PUL or USL (or both) by a hemostat (as in Figure 1) or a speculum (as in Figure 3).

The most frequently used SOs

Clinically, the PUL SOs hemostat tests for stress incontinence (Figure 1, Video S1), and the USL SOs speculum tests (Figure 3), for urge and CPP symptoms, can easily be included in the standard vaginal examination. Other SOs, including intraoperative SOs, will be presented below.

Note: if performed as an outpatient, SO tests must be performed with extreme gentleness, as any excess pressure on the vagina by forceps can cause pain.

SOs which can be performed during clinical examinations

The aim of this work is to present examples of SOs to show that if a particular ligament in the three symptom zones (Figure 2B), is mechanically supported, and it relieves the related symptoms (such as urge and pain) in that zone, a cause/effect (damaged ligament/symptom) can be inferred. If surgery is intended, a positive SO indicates a higher probability of cure with surgical repair. Such SOs are standard predictive interventions for surgeons who follow the IT Paradigm (ITP) for surgical repair of the symptoms in the three zones of the vagina (4-12) (Figure 2B). The SOs which follow will be categorized according to the structural level of damage (yellow circles), numbered 1–4, in Figure 2A,2B.

SOs testing PUL for SUI causation

The relationship of loose PULs to stress incontinence is seen in Video S1. The anatomical and ultrasound analogues of the SO are detailed in Figure 1; the hemostat (white arrow, right ultrasound frame) prevents the PUL lengthening to “L” and so prevents urine loss on coughing; the anatomy and continence are both restored (13) in a manner similar to that of the curative midurethral sling (2,4).

Proof that a midurethral sling does not work by urethral obstruction

The woman is asked to pass urine while the hemostat test shown by Video S1 is preventing SUI. This is not an easy test, but many women manage to do so. Passing urine with the hemostat in situ indicates that the modus operandi of the midurethral sling is not obstructive. Rather it restores anatomy and function, as in the right ultrasound frame (Figure 1).

SO testing PUL causation for stress fecal incontinence (FI)

Stress FI is much rarer than SUI. The hemostat test for stress FI on coughing is exactly the same as that for SUI (Figure 1) (14).

SO testing for PUL causation of mixed incontinence

The testing for “mixed incontinence” is the same as for “genuine” SUI, except that the patient is asked if urge is also relieved. The PUL anchors the pubococcygeus muscle (PCM) which stretches the vagina forwards to provide 50% of the tensioning force to support the urothelial stretch receptors “N” (Figure 1). If the hemostat test (Figure 1), reduces both SUI and urge, it can be predicted that both symptoms may be cured or improved by midurethral sling surgery (Video S2). Video S2 indicates lax PUL as cause of an activated micturition reflex, controlled by PUL support.

SO testing USL causation for urge and pain

The speculum test mechanically supports the stretch receptors, “N” and visceral plexuses from below (15) (Figure 3). The speculum is estimated to control urge and pain in up to 70–80% of women.

Note: excessive backward pressure by the speculum may stimulate more afferents to worsen the pain and urge symptoms. The pain symptoms originate probably from afferent visceral nerve junctions within the visceral plexus, not from the end organ to which it is attributed, as a “referred” pain.

SO local anesthetic (LA) testing for visceral plexus origin of CPP

A definitive test for vulvodynia causation is the Bornstein test: LA injection into the lower part of both USLs reduced vulvodynia pain in ten women who had vulvodynia (16). On testing for vulval hyperesthesia, there was no hyperesthesia in eight women, and in two women, on one side of the vulva only.

The Bornstein test was also applied in women with a validated diagnosis of interstitial cystitis (IC). LA was injected into the lower part of both USLs in three women who had IC and multiple sites of CPP. CPP included vulvodynia, lower abdominal pain, and marked paraurethral tenderness. IC and CPP were relieved for 20 minutes following the LA injection (17).

SO testing loose USL contribution to causation of SUI

In some women, using Allis forceps to approximate USLs can sometimes control SUI on coughing. This is explained by conjoint longitudinal muscle of the anus (LMA) contraction against USL to rotate the bladder base backwards/downwards to close the urethra at the bladder neck (Figure 1).

Note: this test must be performed with extreme gentleness, as the excess pressure during grasping of the vagina by forceps can cause pain.

SO testing USL origin of CPP by cervical palpation

Digital pressure on the cervix by cervical palpation in women with CPP usually reproduces the pain in the areas of the pelvis where pain is perceived by the patient (18).

Note: pressing on the cervix in women with CPP can be very painful and the patient must be warned in advance.

SO testing for nocturia with a roll gauze or other tampon

Shkarupa et al. inserted a sterile gauze roll tampon for a period from 24 to 36 hours (6). They reported statistically validated reduction in overactive bladder (OAB) symptoms (urge, frequency, and nocturia) (6). Similar symptom reductions have been achieved with vaginal tampons, not only for OAB symptoms, but also, urinary emptying symptoms, CPP and, as seen in Figures 4,5, reduction of anterior rectal wall intussusception.

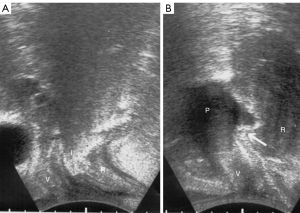

SO assessing USL causation of rectal intussusception with a tampon

A tampon pushed up into the posterior vaginal fornix restores anterior rectal wall intussusception (19). With reference to Figure 4A, anterior rectal wall intussusception “I” was seen during straining. After insertion of a 3 cm × 3 cm × 6 cm vaginal pessary into the posterior fornix (Figure 4B), the pessary elevates the posterior vaginal fornix and, with it, the intussusception (white arrow) even during straining, to (almost) restore normal anatomy (19).

Anatomical rationale for the SO intussusception tampon test

From an anatomical perspective, the close attachment of suspensory USLs to the lateral wall of the rectum means that if the ligaments are loose, both rectum and vaginal apex may prolapse simultaneously, leading sometimes to anterior rectal wall intussusception (Figures 4,5).

SO testing USL laxity as cause for enterocele and apical prolapse

Figure 6 shows an enterocele in a woman years after a hysterectomy. USLs have elongated and become laterally displaced. Approximation of USLs in the OR reduced the enterocele. This test could be painful in the clinic, unless performed with extreme care.

SO testing for CL causation of cystocele

CL weakness is the main cause of transverse defect cyctocele (Figure 7). With reference to Figure 7, the CL SO is based on grasping the prolapsed vagina at the site of the two dislocated CLs (Figure 7B), and approximating them to the anterior lip of the cervix, as in Video S3. The cystocele disappears. If, however, there is also a central cystocele (which happens about 20% of the time), only the proximal cystocele is reduced, as seen in Video S3, and a partial cystocele protrusion remains distally.

SO digital support of bladder can reduce urge symptoms

Digital support of the bladder base (Figures 8,9), can be explained by support of the urothelial stretch receptors. It reduced urge symptoms in 18 of the 20 patients (16). The urge disappeared between 3 and 8 seconds (mean, 5.4 seconds) and returned on removal of the digital support in a comparable period of time. The same test reversed a urodynamic tracing of “Detrusor overactivity” in 6/20 women (16) (Figure 9). The SO in Video S2, controlled an activated micturition reflex with urine loss by digital pressure on the bladder base by supporting the bladder base stretch receptors “N”. Control of urine loss by mechanical support of PUL worked differently. It restored the contractile strength of the forward vector to stretch the vagina more tightly to support the stretch receptors “N” from below.

Palpating the bladder base digitally

Palpating the bladder base can, in some severe cases of OAB, activate the micturition reflex sufficiently for urine to seep out. It fits the hypothesis that “N” (Figure 8), is pressure sensitive to the hydrostatic pressure of the urine above, and digital pressure below. Clearly, this manoeuvre is not recommended unless very well explained. (See Video S4 by permission of Dr. Abranches Monteiro).

Unmasking prolapse as cause of latent SUI

Video S5 demonstrates how the reduction of the cystocele prolapse unmasked SUI, so urine loss was noted during coughing. The coughing was controlled by mechanical pressure at the site of PUL insertion into the midurethra. (See Video S5 by permission of Professor Paolo Palma).

Conclusions

SOs take very little time to perform, provide much information and should be part of a standard vaginal examination. The most useful SOs are for confirming symptom causation by PUL and USL laxity. Unilateral support of the PUL at the midurethra with a hemostat can prevent urine loss on coughing (SUI); USL support in the posterior fornix with a speculum can relieve pain and urge symptoms.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our thanks to Editors Professor Peter Petros and Vani Bardetta for their tremendous help in designing and modifying the article.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the International Society for Pelviperineology for the series “Integral Theory Paradigm” published in Annals of Translational Medicine. Peter Petros (Editor) and Vani Bardetta (Assistant Editor) served as the unpaid Guest Editors of the series. The article has undergone external peer review.

Peer Review File: Available at https://atm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/atm-23-1815/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://atm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/atm-23-1815/coif). The series “Integral Theory Paradigm” was commissioned by the International Society for Pelviperineology without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All clinical procedures described in this study were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for the publication of this article and accompanying images. Human participation in the video was by patient permission on the basis that it was deidentified.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Petros PE, Ulmsten UI. An integral theory of female urinary incontinence. Experimental and clinical considerations. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand Suppl 1990;153:7-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ulmsten U, Petros P. Intravaginal slingplasty (IVS): an ambulatory surgical procedure for treatment of female urinary incontinence. Scand J Urol Nephrol 1995;29:75-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Petros PE, Ulmsten UI, Papadimitriou J. The autogenic ligament procedure: a technique for planned formation of an artificial neo-ligament. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand Suppl 1990;153:43-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Petros PE. New ambulatory surgical methods using an anatomical classification of urinary dysfunction improve stress, urge and abnormal emptying. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 1997;8:270-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Inoue H, Nakamura R, Sekiguchi Y, et al. Tissue Fixation System ligament repair cures major pelvic organ prolapse in ageing women with minimal complications - a 10-year Japanese experience in 960 women. Cent European J Urol 2021;74:552-62. [PubMed]

- Shkarupa D, Zaytseva A, Kubin N, et al. Native tissue repair of cardinal/uterosacral ligaments cures overactive bladder and prolapse, but only in pre-menopausal women. Cent European J Urol 2021;74:372-8. [PubMed]

- Liedl B, Inoue H, Sekiguchi Y, et al. Is overactive bladder in the female surgically curable by ligament repair? Cent European J Urol 2017;70:53-9. [PubMed]

- Caliskan A, Ozeren M, Goeschen K. Modified posterior intravaginal slingplasty: does the additional bilateral tape attachment to the sacrospinous ligament improve the results? Cent European J Urol 2018;71:326-33. [PubMed]

- Petros P. A ligamentous explanation for overactive bladder symptoms as defined by International Continence Society in the female. Cent European J Urol 2018;71:105-7. [PubMed]

- Enache T, Bratila E, Abendstein B. Chronic pelvic pain of unknown origin may be caused by loose uterosacral ligaments failing to support pelvic nerve plexuses - a critical review. Cent European J Urol 2020;73:506-13. [PubMed]

- Petros P. A gynecological perspective of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome may offer cure in selected cases. Cent European J Urol 2022;75:395-8. [PubMed]

- Petros P, Abendstein B, Swash M. Retention of urine in women is alleviated by uterosacral ligament repair: implications for Fowler's syndrome. Cent European J Urol 2018;71:436-43. [PubMed]

- Petros PP, Von Konsky B. Anchoring the midurethra restores bladder-neck anatomy and continence. Lancet 1999;354:997-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Petros P, Swash M. Experimental Study No. 2. A direct test for the role of the pubourethral ligament in anorectal closure. Pelviperineology 2008;27:98.

- Wu Q, Luo L, Petros P. Mechanical support of the posterior fornix relieved urgency and suburethral tenderness. Pelviperineology 2013;32:55.

- Papa Petros PE. Detrusor instability and low compliance may represent different levels of disturbance in peripheral feedback control of the micturition reflex. Neurourol Urodyn 1999;18:81-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bornstein J, Zarfati D, Petros P. Re: Causation of vulvar vestibulitis. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2005;45:538-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Petros PP. Severe chronic pelvic pain in women may be caused by ligamentous laxity in the posterior fornix of the vagina. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 1996;36:351-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gunnemann A, Petros PE. The role of vaginal apical support in the genesis of anterior rectal wall prolapse. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologist. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008:517-8.