Chronic pelvic pain of “unknown origin” in the female

Highlight box

Key findings

• The pathogenesis of chronic pelvic pain (CPP) of apparently unknown origin, may be an inability of loose or weak uterosacral ligaments (USLs) to support visceral pelvic plexuses.

What is known and what is new?

• Pathogenesis of CPP is stated as unknown, with no cure.

• CPP if it co-occurs with symptoms of urge, frequency, nocturia, abnormal emptying, is likely part of the posterior fornix syndrome (PFS).

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• CPP, if part of the PFS, is potentially curable by USL ligament repair.

• As CPP can be relieved with the Speculum Test, this test should be incorporated in every vaginal examination in women with CPP.

Introduction

The key points of the article are summarized in the video abstract (Video S1) and summary (Video S2).

Chronic pelvic pain (CPP) is a major societal problem which occurs in 10–20% of all women, and in all age groups. Pathogenesis of CPP is said to be unknown, with no known cure. According to the International Continence Society (ICS), “genito-urinary pain syndromes are all chronic in their nature, with CPP as the major complaint but with concomitant complaints of lower urinary tract, bowel, sexual, or gynecological in nature” (1). Though learned bodies, learned journals, and expert committees state that the pathophysiology of CPP is unknown, uterosacral ligament (USL) causation of CPP was, in fact, described in the German literature in 1938 by Heinrich Martius from the University of Gottingen, Germany (2). CPP causation by USL laxity was described independently in the English literature in 1993, as part of the posterior fornix syndrome (PFS) by Petros and Ulmsten (3). In 1996, CPP was investigated further, in a laparoscopically controlled trial of 28 women (4) all of whom were referred with severe symptoms of pelvic pain. The mean age was 43 years (range, 20–76, parity 0–8). Six patients (2 of whom were nulliparas) entered the study through accident and emergency. Laparoscopy findings were normal. Native vaginal plication of USLs reported 85% cure at 3 months, and 70% at 12 months (1).

Description of a typical CPP

The pain, typical for the group of 28 women, was described as follows (4): “In its acute state of manifestation, the pain was invariably severe, frequently one-sided, situated low in the right or left iliac fossa, usually relieved on lying down, frequently relieved by insertion of a ring pessary, and reproducible on palpating the cervix and displacing it posteriorly with the patient in the supine position. Although the pain was chronic in nature, it varied considerably from time to time as concerns intensity. Six patients (two of whom were nulliparas) entered the study through casualty as emergency pain becoming sufficiently acute at the time as to seek emergency care. Almost all patients complained of tiredness and irritability by the end of the day. A ring pessary considerably relieved the symptoms in approximately half of the patients, but on occasions, if the pessary was too small, it fell out, or no effect was noted: if too large, the symptoms frequently worsened. Deep dyspareunia was not often volunteered. The pain only occurred on deep penetration or in specific positions. Frequently the patient complained of a constant lower abdominal pain the day after intercourse. Palpation of the cervix generally reproduced the pain experienced during intercourse.”

Aims

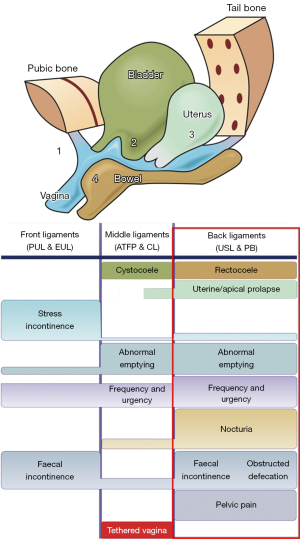

The aim of this review is to demonstrate that CPP, when it co-occurs with bladder and some degree of uterine/apical prolapse (and sometimes bowel problems), is likely a part of the “posterior fornix syndrome”. The remit of this review is confined to the experimental scientific works and surgeries based on the PFS part ITP (4) (Figure 1, rectangle). As such, it is potentially curable by surgically strengthening the USLs.

CPP as part of the PFS

The PFS was described in 1993 as a predictably co-occurring group of pelvic symptoms, CPP, urge, frequency, nocturia, emptying difficulties, post-void urinary retention, caused by USL laxity, and cured/improved by USL repair (3).

Diagnosing the PFS

The pictorial diagnostic algorithm is a useful diagnostic tool for all pelvic symptoms, and it is especially useful for the PFS. The red rectangle in Figure 1 summarizes the bladder and (sometimes) bowel symptoms which can co-occur with the USL-caused pain.

Surgical cure of CPP

The first description in the English literature of cure of CPP, was from a laparoscopically controlled trial by Petros in 1996, performed in mainly premenopausal women, with a mean age of 43 years (4). There were no abnormal abdominal findings. Vaginal plication of USLs was performed. Cure was assessed on a zero sum basis: cured or not cured. Disappearance of CPP at multiple sites was reported by 85% of women at 3 months, and by 70% at 12 months (4). Only CPP symptoms were considered in that study (4). Subsequently, Petros found native tissue USL repair was ineffective for all PFS symptoms in post-menopausal women (including CPP), and he began using a USL sling. Goeschen at al. reported the fate of the PFS (and bowel symptoms) in 198 women who presented with CPP as the main symptom following USL sling surgery (6) (Table 1). Similar cure rates to Table 1 for PFS pain, bladder and bowel symptoms have been recorded by other surgeons (7-10).

Table 1

| Symptoms | Incidence before surgery | Incidence after surgery; rate* | Chi2 test P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pelvic pain | 198 (100%) | 52; 74% | <0.001 |

| Urinary frequency | 127 (64%) | 26; 80% | <0.001 |

| Bladder emptying difficulties | 68 (34%) | 32; 54% | <0.01 |

| SUI | 66 (33%) | 4; 95% | <0.001 |

| ODS | 59 (30%) | 12; 80% | <0.001 |

| Urge incontinence | 55 (28%) | 11; 80% | <0.001 |

| Residual urine >50 mL | 44 (22%) | 20; 55% | <0.001 |

Reused from (6). Copyright 2017, with permission from Pelviperineology. *, surgical cure rate of symptoms. USL, uterosacral ligament; SUI, stress urinary incontinence; ODS, obstructive defecation syndrome.

Table 1 shows the actual proportions of other symptoms in 198 women who presented with CPP and the cure rates for the individual symptoms after USL sling repair (6). In 2008, the PFS was expanded to include fecal incontinence (FI) and obstructive defecation syndrome (ODS) (Figure 1, red rectangle), following a series of defecating proctogram monitored USL repairs with posterior slings (10).

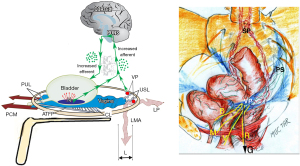

Hypothesis for visceral plexuses (VP) pathogenesis of CPP

With reference to Figure 2, VP, unsupported by USLs, are a main cause of CPP. The discovery of USL laxity as a cause of CPP was published in the German literature in 1938 (3) and independently in the English literature in 1993 by Petros (1,4). Petros hypothesized that the CPP was a referred pain from the inability of loose USLs to support visceral pelvic plexuses, (VP) T11-L2 (1). With reference to Figure 2, Petros hypothesized that the force of gravity “G” stimulated groups of afferent axons within the unsupported VPs to collectively send newly-created afferent impulses to the cortex. These impulses were interpreted as pain, often co-occurring from multiple end-organ sites such as vulva, coccyx, lower abdomen, bladder, anus, but not from the VP relay junction where the hypothesis states they were created. The hypothesis also explains patients complaining of multiple sites of CPP, and simultaneous relief of multiple sites (13) by the Bornstein test, local anaesthetic injection into the USLs at 4 and 8 o’clock, 2 cm from their insertion into the cervix (14), and more simply, by the speculum test (11) (Figure 2).

The telephone exchange hypothesis for multiple end organ pains

With reference to Figure 2, afferent visceral nerves, for example, from pelvic muscles (M). bladder (B), vagina/vulva (V), anorectum (R) (Figure 2, right), run to the VPs where they synapse and become grouped together; VPs act as a relay station where the visceral nerves continue to the spinal cord and cortex; if unsupported by USLs, the nerve junctions can be stimulated by the force of gravity “G” to send off “de novo” impulses to the cortex; these impulses are interpreted as pain arising from the end organs, not from the VPs whence they are caused. Such pains are often relieved by lying down, supporting the concept of gravity as a precipitating cause.

Testing for VP causation of CPP and IC/BPS

The hypothesis of the CPP part of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) being caused by unsupported visceral pelvic plexuses is testable and falsiable: (I) by the speculum test (Figure 2) and (II) by the Bornstein local anesthetic (LA) test.

The speculum test

The speculum test (Figure 2), relieves pain and urge by supporting the USLs and stretching the vagina to support the urothelial stretch receptors “N”. The test, if successful, decreases afferent impulses (small green arrows) pain from the VPs, and urge from “N”; the patient reports lessening of pain in multiple sites, (e.g., “B”, “R”, “M”) (Figure 2) and also, simultaneously, urge.

Relief of multiple CPP sites by LA into VPs

LA injection into the lower end of the USL (Bornstein test) (14), relieved pain within 5 minutes, in multiple sites, vulval (vulvodynia), lower abdominal, paraurethral (pelvic muscles), and pain from palpating the cervix (13). Simultaneous relief of pain in these sites suggests a common origin, from the VP (Figure 2). Surgical relief of multiple pain sites also occurred after native USL plication (4,6-10) and with the speculum test (11).

Relief of CPP and PFS by intravaginal support of ligaments

USL origins of CPP and urgency can be tested by the speculum test (11) (Figure 2), or other mechanical intravaginal support of USLs such as vaginal probes, menstrual tampon, or roll gauze. These devices support USLs similarly to surgical repairs.

CPP and PFS onset perimenstrually or during pregnancy

CPP, bladder urge and emptying symptoms, which are all part of the PFS (Figure 1, rectangle), can be attributed to loosening of the cervical attachments of USL by hormonal softening of the cervix to allow egress of menstrual blood, and in pregnancy, preparation for vaginal delivery.

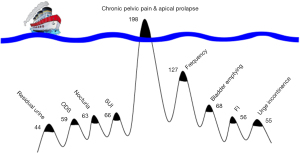

Pescatori iceberg: patients complain of one main symptom

Direct questioning guided by the diagnostic algorithm is required for women with CPP. Goeschen et al. (6) reported that a large proportion of the 198 women who presented with CPP did not complain of other pelvic symptoms. Pain was the “tip of the Pescatori iceberg” and the other PFS symptoms were “below the surface” (Figure 3). The symptoms below the surface had to be revealed by direct questioning (6). Goeschen et al. (6) validated Pescatori’s “iceberg” observations that patients complain of only one major symptom (tip of the iceberg), and that the other (below the surface) symptoms, have to be searched out by direct questioning.

Individual CPP intensity varies widely and can occur with minimal prolapse

How CPP varies widely, even daily was tracked by an individual 67-year-old woman (Figure 4). She had only 1st degree apical prolapse.

Cure or improvement of CPP by non-surgical ligament strengthening

The posterior zone of the algorithm (Figure 1, rectangle) predicts cure or improvement of CPP, bladder and bowel symptoms, non-surgically by squatting-based pelvic floor exercises (16) (Table 2) and surgically by USL repair (4,6-10). Patricia Skilling’s squatting-based exercises (mainly in premenopausal women), four visits in a 3-month course (16), were applied to symptomatic premenopausal women with minimal prolapse. Between 60% and 90% reported a minimum of 50% improvement in symptoms (Table 2).

Table 2

| Condition | >50% improvement |

|---|---|

| Stress incontinence (n=69) | 57 (82%) |

| Urge incontinence (n=44) | 33 (68%) |

| Frequency only (n=12) | 10 (83%) |

| Nocturia (n=32) | 29 (90%) |

| Pelvic pain (n=17) | 13 (76%) |

| Residual urine 202 mL (n=23) | 71 mL |

Reused from Petros P (5). The female pelvic floor function, dysfunction and management according to the Integral Theory. 3rd ed. Heidelberg: Springer Berlin; 2010. With permission from Peter Petros; retains ownership of the copyright. LUTS, lower urinary tract symptoms.

Discussion

The evidence presented indicates a VP causation of CPP, when it is part of the PFS (Figure 1, rectangle). The “telephone exchange” hypothesis which seeks to explain grouping of afferent visceral nerves from multiple end-organ sites is supported by the following:

- Relief of multiple end-organ CPP sites was noted following LA injection into the site of the VPs at the lower end of the USLs (13,14).

- Relief of multiple end-organ pain sites occurred with the speculum test (11).

- Simultaneous cure of multiple end-organ pain sites occurred with USL surgery (4,6-10). Pain relieved or cured by these interventions, included separately denominated CPP conditions such as vulvodynia, IC/BPS, pelvic muscle spasm, cervical excitation pain, deep contact dyspareunia, lower abdominal pain, coccydynia. Simultaneous cure of these seemingly widely varied conditions indicates that they may all be different phenotypes of CPP deriving from the inability of weak USLs to support the VPs (Figure 2).

- Observation that pains in multiple sites are often relieved by lying down (4). This observation led to the hypothesis that the stimulus for the pain was the force of gravity (4).

Though high cure rates for CPP and other PFS symptoms have been reported using slings (6-10), the landscape has altered. Since about 2011, any mesh products other than for stress urinary incontinence became progressively banned in many countries world-wide. Native USL repair is a good option but only for premenopausal women (17). In a comparative study, Shkarupa et al. demonstrated high cure rates for overactive bladder (OAB) symptoms and prolapse in premenopausal women, but gave catastrophically low results in post-menopausal women, probably because of collagen breakdown in ligaments after the menopause (17).

Figure 2 summarizes the central hypothesis of this work, that gravity and/or muscle movements stimulated VP junctions which contain grouped afferent visceral nerve axons from end organs (Figure 2). These fire off “new impulses” which the cortex interprets as pain or injury originating from the end organ itself (12). The axon groupings in the VP (Figure 2), explain CPP occurrence in multiple sites, relief with LA and after successful surgery (4,6-10).

However, the VP hypothesis for pain causation does not by itself explain the histological findings, presence of inflammatory cells and neuroproliferation at the end organ, for example, vulva (18), and urothelium (19). These findings (12,18,19) led to a further hypothesis to explain these changes: the cortex receives signals from the end organ which are sensed as “pain” (or injury) from the end organ; any “injury”, be it infection or trauma, elicits a similar inflammatory response, anti-inflammatory cells at the site of injury. Though the impulses are hypothesized to originate from the VP nerve synapses, the cortex interprets the signals as coming from the end organ itself (Figure 2, yellow lines); it sends efferent impulses to the end organ; these impulses activate “sleeper cells” to produce the tissue reactions histologically observed in IC/BPS and vulvodynia.

Conclusions

CPP of unknown origin has several forms (phenotypes): vulvodynia, IC/BPS, pelvic muscle spasm, lower abdominal pain, low sacral backache, and coccydynia (Figure 2). When CPP co-occurs with other symptoms (Figure 1, rectangle), the pain is likely caused by lax USLs. If CPP is alleviated by the speculum or other test, it is an indication that the pain can be improved or cured surgically (4,6-10), or non-surgically, by the Skilling squatting-based exercises (16) or even various intravaginal devices which mechanically support the USLs. The Pescatori iceberg principle needs attention by the practising physician, as patients complain only of one major symptom, even when they have multiple symptoms (Figure 3). Almost invariably, other LUTS symptoms lie “below the surface”, and these have to be sought out by direct questioning as mandated by Pescatori himself (20). The Integral Theory Symptom Questionnaire (ITSQ) (15) is comprehensive, and it will locate all relevant LUTS symptoms, grade them, and indicate with a high degree of certainty, which of the three zones is causing the LUTS. The algorithm (Figure 1), is an excellent, quick, aide memoire for separating VP origin pain from, say, endometriotic or pudendal nerve pain.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our thanks to Vani Bardetta for her proofreading and administrative services for this article.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the International Society for Pelviperineology for the series “Integral Theory Paradigm” published in Annals of Translational Medicine. Peter Petros (Editor) and Vani Bardetta (Assistant Editor) served as the unpaid Guest Editors of the series. The article has undergone external peer review.

Peer Review File: Available at https://atm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/atm-23-1758/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://atm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/atm-23-1758/coif). The series “Integral Theory Paradigm” was commissioned by the International Society for Pelviperineology without any funding or sponsorship. P.P. serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Annals of Translational Medicine from October 2022 to September 2024. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn 2002;21:167-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martius H. Über einen häufigen gynäkolo- gischen Symptomkomplex. Arch Gynak 1938;166:332-5. [Crossref]

- Petros PE, Ulmsten U. The posterior fornix syndrome: a multiple symptom complex of pelvic pain and abnormal urinary symptoms deriving from laxity in the posterior fornix. Scand J Urol Nephrol 1993;27:89-93.

- Petros PP. Severe chronic pelvic pain in women may be caused by ligamentous laxity in the posterior fornix of the vagina. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 1996;36:351-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Petros P. The female pelvic floor function, dysfunction and management according to the Integral Theory. 3rd ed. Heidelberg: Springer Berlin; 2010.

- Goeschen K, Gold DM. Surgical cure of chronic pelvic pain, associated bladder & bowel symptom by posterior sling in 198 patients validates the Pescatori Iceberg principle of pelvic in 198 patients validates the Pescatori Iceberg principle of pelvic symptom cooccurrence. Pelviperineology 2017;36:84-8.

- Inoue H, Nakamura R, Sekiguchi Y, et al. Tissue Fixation System ligament repair cures major pelvic organ prolapse in ageing women with minimal complications - a 10-year Japanese experience in 960 women. Cent European J Urol 2021;74:552-62. [PubMed]

- Wagenlehner F, Muller-Funogea IA, Perletti G, et al. Vaginal apical prolapse repair using two different sling techniques improves chronic pelvic pain, urgency and nocturia: A multicentre study of 1420 patients. Pelviperineology 2016;35:99-104.

- Inoue H, Kohata Y, Fukuda T, et al. Repair of damaged ligaments with tissue fixation system minisling is sufficient to cure major prolapse in all three compartments: 5-year data. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2017;43:1570-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abendstein B, Brugger BA, Furtschegger A, et al. Role of the uterosacral ligaments in the causation of rectal intussusception, abnormal bowel emptying, and fecal incontinence-a prospective study. Pelviperineology 2008;27:118-21.

- Wu Q, Luo L, Petros PEP. Case report: mechanical support of the posterior fornix relieved urgency and suburethral tenderness. Pelviperineology 2013;32:55-56.

- Goeschen K, Gold D, Liedl B, et al. Non-Hunner’s Interstitial Cystitis is different from Hunner’s Interstitial Cystitis and may be curable by uterosacral ligament repair. Urol Int 2022;106:649-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Petros PEP. Interstitial cystitis (painful bladder syndrome) may, in some cases, be a referred pain from the uterosacral ligaments. Pelviperineology 2010;29:56-9.

- Zarfati D, Petros PP. The Bornstein Test- a local anaesthetic technique for testing uterosacral nerve plexus origins of chronic pelvic pain. Pelviperineology 2017;36:89-91.

- Wagenlehner FM, Fröhlich O, Bschleipfer T, et al. The Integral Theory System Questionnaire: an anatomically directed questionnaire to determine pelvic floor dysfunctions in women. World J Urol 2014;32:769-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Skilling PM, Petros P. Synergistic non-surgical management of pelvic floor dysfunction: second report. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2004;15:106-10; discussion 110. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shkarupa D, Zaytseva A, Kubin N, et al. Native tissue repair of cardinal/uterosacral ligaments cures overactive bladder and prolapse, but only in pre-menopausal women. Cent European J Urol 2021;74:372-8. [PubMed]

- Bornstein J, Goldschmid N, Sabo E. Hyperinnervation and mast cell activation may be used as histopathologic diagnostic criteria for vulvar vestibulitis. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2004;58:171-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Regauer S, Gamper M, Fehr MK, et al. Sensory Hyperinnervation Distinguishes Bladder Pain Syndrome/Interstitial Cystitis from Overactive Bladder Syndrome. J Urol 2017;197:159-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pescatori M, Spyrou M, Pulvirenti d’Urso A. A prospective evaluation of occult disorders in obstructed defecation using the ‘iceberg diagram’. Colorectal Dis 2007;9:452-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]